Kings of comedy: When Muir & Norden bossed the BBC

On the stepladder to power and influence, the humble writer is usually perched precariously on one of the lowest rungs. This is certainly so in the world of show business, where most writers are used to staring up at many more important people's bottoms. There was, however, a brief but memorable period in the 1960s when this order was inverted and a pair of comedy writers - Frank Muir and Denis Norden - suddenly found themselves up at the top and looking down. What makes this story all the more remarkable is that Muir and Norden did not have to fight to acquire this power - it actually landed in their laps.

It happened, appropriately enough, on April Fools' Day in 1959, when the BBC announced its intention to appoint them its official 'Consultants and Advisors on Comedy'. It was an unprecedented arrangement which would see them given their own executive base at the soon-to-be-opened Television Centre, with the power to recruit artists, commission programmes and, to a great extent, control the cultivation of comic content within the Corporation.

How, and why, had it come about? There were essentially three contributing factors: a new broom at the BBC; a growing sense of competitiveness; and a greater need for in-house talent.

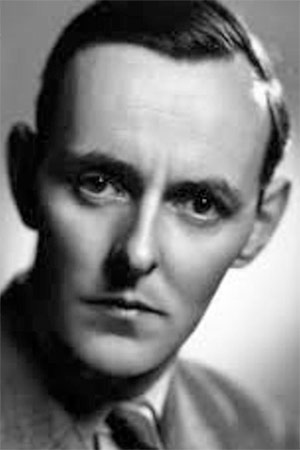

The new broom was Eric Maschwitz, who had recently returned to the BBC after a twenty-one year absence to become its Head of Light Entertainment. This tall, rather handsome, charming man, since his last spell with the broadcaster, had made a name for himself in show business as a novelist, a writer and producer of successful musicals, plays and revues, and a gifted lyricist of such popular songs as These Foolish Things and A Nightingale Sang In Berkeley Square.

Having been educated at Cambridge (where his regular tennis partner was Albert, the future King George VI), and acquired invaluable practical experience working in the theatres of London and the studios of Hollywood, he possessed both an intelligence and a worldliness that was unparalleled in those days in British television. He also exuded an air of authority - earned as an artist as well as an executive - that his more conventional colleagues had no real choice but to accept and respect.

He had not returned to the BBC to keep its traditional attitude to entertainment ticking over. He had come back to revise it, reinvigorate it and enrich it.

This leads us to the second factor: a growing sense of competitiveness. Ever since the arrival of commercial television in Britain in 1955, the BBC had seen some of its best entertainment writers, directors and performers get tempted over to 'the other side' - where they were promised greater freedom and much better pay - and, as a consequence, its own output was struggling to match the freshness, energy and feeling of fun now being projected by its youthful rival. Maschwitz recognised this and was determined to start fighting back.

This leads us to the third factor: the greater need for in-house talent. Commercial television was not the only new institution that was clawing away some of the Corporation's 'home-grown' creative personnel. The 1950s had also seen the emergence of increasingly powerful independent writers' agencies - most notably Spike Milligan and Eric Sykes's Associated London Scripts - which were now not only selling material to the BBC (as well as to ITV) but also pre-formed programme and format ideas. Maschwitz knew, therefore, that if he was going to rejuvenate the BBC's entertainment identity, he would also need to rebuild its entertainment infrastructure.

This is where Frank Muir and Denis Norden came in. Maschwitz, upon arriving back at the BBC, was exasperated by the amateurism, and ambivalence, that was evident throughout the department he had inherited, which seemed to be full of people who would much rather have been somewhere else doing something more 'important'. The very fact, for example, that the more-established executives had snootily dubbed that section of its operation 'Light Entertainment' suggested to the new broom that too few of them truly believed in what they were doing, treating the idea of entertaining the masses as something that was probably really beneath them.

'"Light entertainment"?' he barked. 'What is its alternative? "Heavy entertainment"? Or perhaps "Dark entertainment"?' He had no time for such conceptual timidity, nor for such cautious and conservative colleagues.

He knew what he wanted - good entertainment, not mediocre entertainment, the best entertainment possible, with all the richness of its range - and he knew that he needed like-minded thinkers to start delivering it. These were the kind of people who, like Maschwitz himself, had worked on the factory floor, slaving over the typewriter and stepping about the stage, and thus understood what it took to create as well as commission the kind of programmes that appealed to, and pleasantly surprised, the best part of the whole nation.

Frank Muir and Denis Norden, by the late-1950s, were just what Maschwitz was looking for: relatively young (they were still in their thirties), bright, talented, distinctive comedy writers who were currently at the top of their game. Take It From Here, the radio show that they had created back in 1948 for the comedian Jimmy Edwards, had gone on to be one of the BBC's biggest hits of the decade, regularly attracting an estimated 20 million listeners. Full of fast-paced, cleverly-crafted and inventive sketches, and featuring the refreshingly unsentimental mini-sitcom 'The Glums,' it was intelligent, amusing, engaging and inclusive, and was inspiring a whole new generation of comic writers to follow its example.

Maschwitz thus wasted no time at all in sounding them out as to his plans. Frank Muir's later recollection of their meeting, in his book A Kentish Lad, would prove more than a little foggy - he got the wrong man (he thought it was Maschwitz's assistant, Tom Sloan, who made the invitation) and the wrong year (he thought it was 1960 but it was most definitely 1959) - but there was no doubt as to how eagerly they accepted the offer: 'Den and I signed up at once'.

They were less than impressed by their initial accommodation - Television Centre was still being built (it would not formally open for business until the following summer), so the BBC's two new comedy tsars found themselves having to make do for the time being with a Portakabin on the back of a lorry in the car park. They were very pleased indeed, however, with their new responsibilities and authority.

Independently of Maschwitz and the BBC, Muir and Norden had already begun a campaign to promote and protect their fellow writers, which would soon see them co-founding (with thirteen others) The Writers' Guild of Great Britain, and now they had wide-ranging powers to do so from inside the national broadcaster. It was a remarkable opportunity, and they were determined to make the most of it.

Their first task, they told reporters, would be to find and nurture new writing talent, and they promised to travel the country and tour the clubs and theatres in search of it. Their second task, as they saw it, was to try to build better working relationships between writers and performers, because, they argued, the best comic output came from the ongoing interaction between author and actor. Their third task, they said, was to get more comedy shows and series on the BBC. 'Take It From Here is heard in every English-speaking country in the world,' they observed. 'We'd like to do that sort of thing on television. We want shows that run year after year.'

They also promised to create a culture within the Corporation that was active rather than passive, and far more keenly attuned to changing interests, needs, tastes and fashions. An effective producer of comedy, they explained, has to be 'studying and working on public attitudes all the time. You have to see what people are going to laugh at next'.

Warning that no one should believe that they were intending to turn the BBC 'into a writers' paradise', they stressed that they were committed to the Maschwitz model of collaborative regeneration, working to make writers thrive for the BBC rather than merely within the BBC. 'We just hope,' they concluded, 'that with our experience, those who want to start writing will get help, and that we'll be able to blend writers with the right artists.'

Deep down, however, both Muir and Norden were suffering, at least at the start, from a degree or two of Imposter's Syndrome - a feeling of inadequacy that was gleefully exacerbated by Mel Brooks, whom they soon got to meet on their first 'fact-finding' trip to New York. Introduced to him in the offices of the William Morris Agency as 'Britain's Comedy Consultants,' Brooks leapt up in mock amazement and gasped, 'You mean, you KNOW???'

Back in London, with their large office on the fourth floor of the BBC's new Television Centre now fully operational, they moved in and did their best to convince themselves, as well as everyone else, that they knew what they were doing. Pile after pile of speculative scripts started to come pouring in, which the two men read and reported on dutifully; the departmental committee meetings were attended on a regular basis; and occasional 'consultative meetings' were held between either Maschwitz or Sloan whenever one or the other felt the need for a more private and specific discussion.

They adored having Maschwitz as their boss. His recent autobiography had been called No Chip On My Shoulder, and it was an apt title for a man who had no time for haughtiness or hierarchies (and was also disarmingly self-deprecating: when, years before, someone asked him what he was up to, Maschwitz said that he was staging a production of his musical Goodnight Vienna in Lewisham. 'And how is it going?' inquired the friend. 'About as well as a production of Goodnight Lewisham would be going in Vienna,' came his reply).

He was constantly supportive, appreciative and thoroughly entertaining, helping his two new colleagues settle in at the Corporation by taking them frequently to lunch at the BBC's senior dining room (which he dubbed the 'Café Sordide'), where he would link everyone together through laughter. He called his eighteen or so producers 'my ragged army', treasured all of their individual personalities and eccentricities, and gave affectionate nicknames to each one.

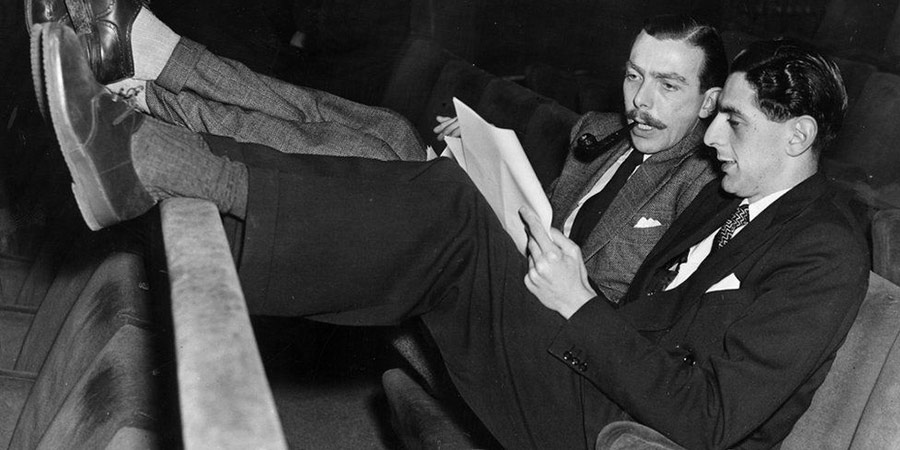

He referred to Muir and Norden as 'Los Layabouts', because, whenever he slipped out of his office and into theirs to avoid someone or other requesting an unpleasant managerial chore, he usually found them sitting back on opposite sides of their large desk, resting their feet on the top while staring up in silence at the ceiling. Rather than objecting to this laid-back scene, Maschwitz simply joined in, pulling up a chair, putting his own feet up on top, and absent-mindedly twanging his crimson braces as he reminisced about his many exotic adventures in various parts of the world.

One of his stories went as follows:

I had a mistress in those days who was a ballet dancer with the Vienna Opera. On one occasion, I flew over to Vienna and had a wholly delightful weekend. On the Monday morning, a shade hung-over, I was in a taxi on the way to the airport when I glanced out of the back window and saw that we were being closely followed by a large Alsatian dog pedalling a bicycle with a pipe in his mouth. This was unnerving and I almost gave up champagne and the Vienna corps de ballet there and then, but the bicycle passed us at a traffic light and I saw that it was actually being pedalled by a small Viennese man in a cap, hidden from our view by his huge Alsatian dog which he had sat in the basket on the handlebars. I am happy to say that I have no idea how the dog came to be smoking a pipe. Some mysteries should never be explained, should they?

Another tall tale, prompted by his suggestion one afternoon that the three of them might co-edit a book with the working-title of My Most Memorable Fuck, proceeded thus:

My own contribution would be set during the war when I was in Intelligence and doing a course of something furtive at Woburn Abbey. I was spending most evenings steadily trying to seduce a Wren officer, a delightful creature with promisingly wicked eyes. Eventually, on a beautiful evening after dinner, I took her for a walk in the grounds. Trees and long grass and moonlight. We lay down and I undressed her. With her black silk stockings and white thighs it was like peeling a nut. We were in the middle of pleasure when the ground began to shake. 'Is the earth moving for you?' she whispered. 'Yes. But it really is moving!' I said. 'It feels like a charging bison!' Which is what it was. We had strayed into the zoo area of Woburn Park and several tons of angry bison was thundering on its way to deal with us. This was coitus interruptus on an operatic scale. My Wren lady and I semi-dressed in haste and scrambled to safety clutching bits of clothing, all passion spent and never, of course - it never can be - rekindled.

Muir and Norden, delighting in all of these digressions, not only warmed to Maschwitz as a character. They also trusted him, and respected him, as an executive whose creative abilities were probably as prodigious as any of those who were working beneath him.

'BBC's Light Entertainment [Department] was unique,' Muir would say, 'in having a Head who, if he wanted a musical show and couldn't find one he liked, was perfectly capable of writing one himself'. The same was broadly true for comedy shows, and even drama shows.

Maschwitz was thus a friend and fellow artist as well as a boss. It was no surprise that Muir and Norden bonded so well with him.

Emboldened by such an extraordinary in-house mentor and manager, the two writers warmed to their task. They spent their first few months immersed in sketching out possible projects and planning initiatives to put their expertise to the best possible use.

It was not long, however, before both parties - Muir and Norden and the BBC management - started to become frustrated with the consultancy role. The source of this frustration, ironically, was the fact that the writers still wanted to write.

When Muir and Norden had agreed to join the BBC, they did so on one condition: they would be allowed to continue with their own writing projects. This was not only down to creative ambition; it was also because, as freelance writers, Muir and Norden had been earning the kind of money that was far above any in-house staff scale, so they were not prepared to put up with a large pay cut, as well as the stalling of their primary career, for several years' service.

Eric Maschwitz accepted their request unquestioningly - after all, he, too, was a freelance at heart - but he had not counted on the BBC's bureaucracy getting involved. Once the arrangement had been noticed internally, some or other guardian of the BBC's rules and regulations (ignoring the fact that such arrangements had been conveniently overlooked on several occasions in the past) decided that they could not simultaneously be paid as executive consultants and series writers.

The consequence was that the BBC ended up effectively sabotaging its own experiment. The money men (who had been immediately suspicious of the whole unconventional enterprise) ruled that Muir and Norden would be obliged to go into purdah whenever they were working on a series - so when they were currently writing comedy, they could not actively advise or be consulted about comedy.

The BBC then proceeded to make the situation even more ridiculous as time went on, because they liked Muir and Norden's various series so much they kept asking for more of them - thus robbing themselves of more and more of the consultancy work for which they had been hired. Maschwitz, of course, was furious and Muir and Norden were, increasingly, disheartened.

What the decision did was to rob almost everything that they sought to pursue of any real momentum. Commissions could be still be made, talent could be recruited, plans could be discussed, scripts could (sometimes) be read and occasional advice could be given, but more ambitious longer-term projects would now be compromised by the fact that Muir and Norden were obliged to pretend that they were not there for several months each year.

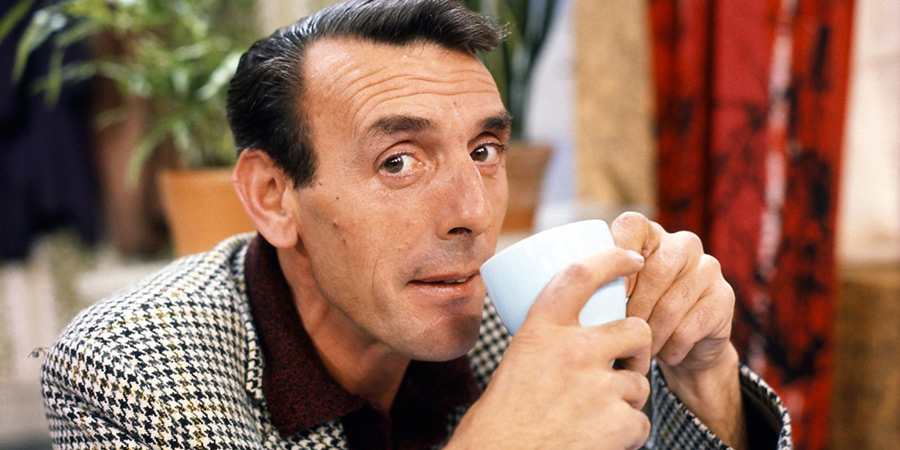

As writers, they flourished. During their 'holidays' from their day job (a card saying 'IN PURDAH' was pinned on their office door), they supplied the scripts for a steady flow of TV comedy shows, including Whack-O! (1956-60); The Seven Faces Of Jim (1961); Brothers In Law (1962); Six More Faces Of Jim (1962); More Faces Of Jim (1963); and Mr Justice Duncannon (1963). They also contributed material for other shows, including That Was The Week That Was, Showtime, and Christmas Night With The Stars. In addition to all of this, they also co-starred (first on radio and then television) in the panel show My Word!.

As 'Consultants and Advisors', however, they had to make do with relatively brief but manic periods of hyper-activity, during which time they tried to keep all kinds of plates still spinning on the tips of sticks. Their colleagues, knowing that their availability was now time-specific, often sought to get their money's worth by asking for their advice on a range of subjects that went far beyond the realm of comedy.

Tom Sloan, for example, marched into their office one day and asked for their opinion on his plan to cancel the popular police series Dixon Of Dock Green, which had been running since the mid-1950s. 'Jack Warner is too old for a police sergeant,' he said, 'he can hardly walk!' The two writers pointed out that, as unrealistic as some aspects of the show may have become, it had only recently been voted the second most popular programme currently on British television and was attracting an estimated audience of 13.85 million every week. Somewhat reluctantly, Sloan accepted their advice to leave it well alone and the show was saved.

In spite of all the distractions and disruptions, however, Muir and Norden did manage to make a difference in their formal roles. They succeeded, for example, in helping to plan, launch and maintain such memorable comedy series as That Was The Week That Was; Hancock; Steptoe And Son; A Life Of Bliss; Showtime; On The Bright Side; It's A Square World; Moody In...; Sykes And A...; The Rag Trade; The Big Noise; Citizen James; The Eggheads; Dial RIX; Hugh And I; Comedy Playhouse; and Here's Harry.

They also remained discreetly available to all such shows, and many others, as unofficial sounding-boards, script editors and occasional trouble-shooters. An example was their prompt response to a problem during the preparation of the very first episode of Sykes And A.... Eric Sykes, its writer and star, had suddenly lost faith with a certain point in the script and, with the clock ticking, was struggling to find a solution, so Muir and Norden were summoned from their office and the obstacle was swiftly overcome.

'Eric later said,' Frank Muir would recall, 'that the sight of us charging in through the door of the rehearsal room was like the arrival of the US Seventh Cavalry. It was quite a minor blockage he had with his scene and Eric was easy to help; all one did was suggest a line and Eric immediately thought of a better one; it was just a matter of stimulating his own creativity into action.'

This was the kind of support that Eric Maschwitz had originally envisioned for the pair: experienced, tried-and-tested, trustworthy advice from fellow comedy writers, called on as and when it was needed, in the service of BBC shows. It actually happened on a fairly regular basis, always calmly, quickly and constructively, and usually without anyone outside the productions in question ever knowing of any such involvement.

They also did their best to encourage up-and-coming writers. Although, in a bolted horse/stable door scenario, the independent agencies were by this time all-too adept at finding, signing up and nurturing new talent, Muir and Norden still managed to encourage, advise and assist numerous young (and not-so young) scriptwriters, including, among others, Ronald Chesney and Ronald Wolfe, John Law, Christopher Bond, Richard Waring, John T. Chapman, and Vince Powell and Harry Driver. They were also instrumental in helping Ronnie Barker establish himself in television (as a regular in The Seven Faces Of Jim in 1961), as well as promoting plenty of other promising performers.

One of their less successful enterprises was their repeated attempts to persuade their favourite American comedy stars to record a prestigious special for BBC TV. They flew to Los Angeles in the hope of getting Jack Benny to commit to a show, but, although he charmed them thoroughly with his kindness and good humour, he politely declined the offer on the grounds that he was already booked to make an appearance on the Royal Variety Show later the same year and was obsessing over that particular spot.

They did manage to sign up Shelley Berman (one of the most distinctive and popular young stand-ups of the time, who many years later would enjoy a further wave of fame for playing Larry David's father in Curb Your Enthusiasm) - his self-titled special would be broadcast at the end of 1961 - as well as the much-admired Canadian double act of Wayne and Shuster - whose Wayne And Shuster In London would go out a year later.

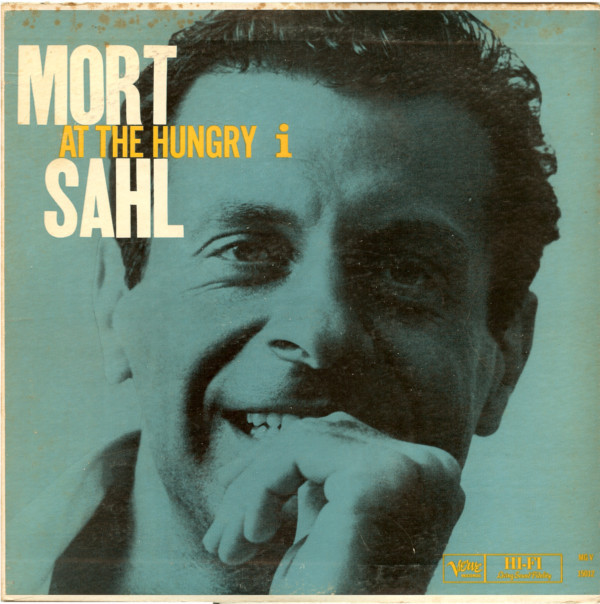

Their most eye-catching import, however, turned out to be something of a flop. Mort Sahl, whose frantically passionate style of delivery had won him the soubriquet of 'the rebel without a pause', was arguably the most critically-admired and 'cool' stand-up comic in the US at that time. His willingness to walk on to the stage with that day's newspaper and launch into some inspired riffs of up-to-the-minute social and political satire was inspiring a whole new generation of performers, from Lenny Bruce to Woody Allen, and an album of his night club act, At The Hungry I (1960), was in the process of being played to death by millions of fans on both sides of the Atlantic.

It was understandable, therefore, that Muir and Norden considered it a huge coup to have convinced him to come to London and film a show for the BBC. Unfortunately, however, he would end up letting them down.

Produced by Bill Cotton Jnr, The Mort Sahl Show, which was broadcast in July 1961, was one of the most-hyped TV shows of the year, but on the night of the recording, much to Muir and Norden's (and Bill Cotton's) disappointment, the comic shuffled on stage and merely reprised all of the routines from his already over-familiar album.

Neither Muir nor Norden ever professed to know why a comedian famous for his improvisatory skills had elected, on that particular night, to take such an easy, lazy, route. Bill Cotton, however, most certainly did have a theory.

'The truth of the matter,' he later told me, 'was that Mort Sahl had spent the entire week's "preparation" screwing Joan Collins in the Dorchester Hotel! That's what happened! We'd flown him over, put him up, and he did no homework at all - except on Joan - he just used all of this old material. And for the recording we'd assembled an illustrious, intellectual audience of people like Jacob Bronowski and Jonathan Miller, who were all dying to hear what biting new satirical stuff he was going to say about England - but he didn't say anything much about politicians as far as I could tell. So the whole thing was a damp squib and he had the nerve to blame [the BBC's] Light Entertainment department for it, complaining that we didn't understand satire!'

Such setbacks, however, were the exception to the rule during Muir and Norden's reign. In spite of the internal politics that at times had blunted their bite, they spent four largely productive years restoring the BBC's reputation as the nation's great patron of comedy. Then, quite abruptly, it all came to an end.

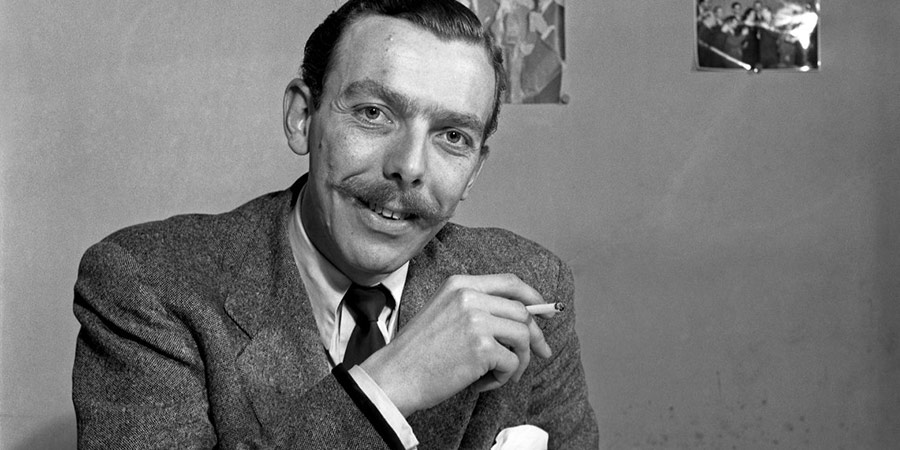

Eric Maschwitz quit the Corporation. Although he had overseen innumerable improvements in his department's methods and morale, and enhanced the appeal of the BBC's entertainment output not only domestically but also internationally (one newspaper at the time judged him 'Europe's most popular TV boss'), he had felt under-appreciated beyond his devoted staff for some time. Then, early in 1963, his superiors saw fit to promote the much-younger Donald Baverstock over his head to be the new Controller of Programmes for BBC One, and Maschwitz decided that, at the age sixty-two, he had had enough.

Having been courted assiduously by other entertainment companies for some time, he accepted an offer from the ambitious commercial channel Rediffusion to become a producer of special projects. Tom Sloan, his former deputy, was appointed Head of Light Entertainment in his place.

All of the free spirits who had flourished under Maschwitz now suddenly felt that they had floated into captivity. The brilliantined, moustachioed, rather military-looking Sloan, though an eminently decent and well-meaning manager, was as dour a figure as his predecessor was droll. He wasted no time in making it clear that the playfulness of the Maschwitz era was well and truly over when, in his first brief and brisk meeting with all his assembled staff, he declared ominously, 'This Department has a lot of work to do and we are all professionals, so you can forget any of that "ragged army" nonsense.'

Muir and Norden (like a few others) decided then and there that they no longer belonged. Within a week, they had joined Maschwitz over at Rediffusion, signing a deal to write and appear in their own weekly series, starting that autumn.

The experience of being bosses, however, had an unexpected impact on the two writers. It broke them up.

Norden was only too happy, by this time, to be free of the responsibility of being an executive. 'I loathed it,' he later said, referring particularly to the latter part of the period, 'and was very bad at it.' Muir, on the other hand, had some regrets that it was all over. 'Frank loved it,' Norden reflected, 'and was very good at it.'

'I could do something,' Muir would concur. 'Because I was there, other people did better things than they would have done if I wasn't there. I liked the companionship of working in a department, of working with producers. I think producers liked having me to talk to. It's marvellous to find you have a sort of tiny aptitude which you didn't realise was there - that of creating an atmosphere of work.'

Unsettled by their sudden switch to ITV from the BBC (Norden would describe the transition as 'like leaving a monastery and joining a strip club'), they struggled to regain their old focus. Their new show, a very loose adaptation of the popular book by George Mikes called How To Be An Alien, would turn out to be their first flop - and a big flop at that.

The series, Norden would recall, 'was adopted by the critical fraternity as a sort of template against which other unsuccessful shows could be measured. Thus, for ages after it had disappeared from the schedules, we would pick up a newspaper or magazine and the TV column would present us with something along the lines of "Last night's such-and-such a show was execrable. Not as execrable, of course, as How To Be An Alien, but..."'.

After that traumatic episode, the writers needed to get away from it all and lick their wounds. Muir took his family off to Corsica for a vacation. Norden took his to the South of France.

When they returned, Muir was contacted by Tom Sloan. Sensing belatedly that, as someone with no experience of the creative aspects of entertainment, he was in danger of seeming too aloof and out of touch with the talent in his own department, Sloan was now ready to backtrack a little and restore some of the old Maschwitz atmosphere. He wanted two assistants: Bill Cotton, as Head of Variety, and Frank Muir, as Head of Comedy. Both men, when offered their respective roles in October 1964, accepted.

It meant that Muir and Norden, as a writing partnership, was effectively over. They would remain great friends, and occasional co-performers, for the rest of their lives, but from this point on they would walk on different paths.

While Norden worked for a while in Hollywood and other film-making bases (co-writing such movies as Buona Sera, Mrs. Campbell and The Bliss Of Mrs. Blossom, both 1968, and The Statue, 1971) and then drifted into the role of a Steve Allen-style TV presenter (most notably as the host of ITV's long-running It'll Be Alright On The Night), Muir embraced the role of the executive. Launching such ground-breaking shows as Not Only... But Also..., On The Margin, The Frost Report and Till Death Us Do Part, and nurturing a new generation of university-educated comedians (including most of the future Monty Python troupe), he stayed at the BBC until November 1967, when he agreed to move over to the soon-to-be-formed London Weekend Television as Head of Entertainment.

He only lasted there until September 1969, when he and five colleagues resigned in protest at the sacking of the much-respected managing director Michael Peacock, but he still managed to help spark a mini golden era for comedy at ITV with such shrewd commissions as Please Sir!; On The Buses; We Have Ways Of Making You Laugh; Never A Cross Word; Doctor In The House; and The Complete And Utter History Of Britain.

After that, for a long time, it was back to business as usual as far as TV comedy was concerned. Just like in the old days, the suits called the shots and the scriptwriters complied.

It should be remembered, however, that Eric Maschwitz's noble experiment actually worked rather well, and, but for internal interference, could have worked even better. What Muir and Norden showed was that having a little creative experience, as the hyphen between artists and management, can be an excellent thing for both parties, and an excellent thing for audiences, too.

It's often joked that 'those who can't, manage those who can'. It would be better for both, however, if they met on the same rung of the ladder every now and then, and helped each other to progress.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more