Desperately seeking Sid

On the evening of 28th March 1948, inside a grand, dark-arched, Tudor-style building on 1765 North Sycamore Street in Hollywood, the Masquers Club - an exclusive organisation set up by the stars of the movie industry to celebrate the very best of their special breed - held a 'Testimonial Dinner' in honour of a gifted young comedian who was visiting from England. Bob Hope was there as MC. Cary Grant was there as well; as were Jack Benny, Bing Crosby, Groucho Marx, Stan Laurel, Fred Allen, Ronald Colman, Danny Kaye and many other stellar names. They all bowed to and toasted this English comedian, and then performed a number of special skits and sketches just for him. This particular comedian meant that much.

Who was he? He was Sid - Sid Field.

'Sid who?' you probably will ask. That is the sad thing. Everywhere you look at British comedy, everywhere you look at its best performers, from the 1950s through until now, you will see a trace of Sid Field - and most of you, through no fault of your own, won't recognise it.

There is currently a blind gap in Britain's pantheon of comic greats. Sid Field has gone missing, and hardly anyone among the comedy-loving public seems to have noticed.

It is painful to think that the vast majority of people - even the vast majority of people who consider themselves to be big fans of British comedy - will keep on asking, 'Sid who?' It is painful because, for anyone who does know about this performer, Sid Field was not just a rare comic genius, but also arguably the most influential - but least appreciated - contributor to this country's post-war comedy heritage. The mention of his name ought to make chests swell with pride; instead, more often than not, it makes shoulders shrug with ignorance and incomprehension.

Throughout the last half century or so since his death, Sid Field has been the professional comedian's very own invisible friend. All of the undisputed greats of this era have continued to love and revere him, while fewer and fewer of their fans have been able to remember who on earth he actually was, let alone what he actually did. The man is nowhere, and yet, if the general public only knew it, his legacy is everywhere.

Do you remember Tony Hancock? What about Peter Sellers, or Frankie Howerd, or Eric Morecambe, or Terry-Thomas, or Benny Hill, or Tommy Cooper, or Ken Dodd, or Larry Grayson or Ronnie Barker? Remember most or all of them? Well, they all watched, studied and worshipped Sid Field.

Have you ever seen James Beck playing the spiv Private Walker in Dad's Army? That was an acknowledged copy of a character created by Sid Field.

Have you heard Kenneth Williams and Hugh Paddick playing Julian and Sandy in the radio show Round The Horne, or seen John Inman playing Mr Humphries in Are You Being Served?? All three of those, again, were acknowledged copies of characters created by Sid Field.

Have you seen several of the characters in The Dick Emery Show, or Harry Enfield & Chums or Little Britain or The Fast Show? Those, too, with just a little light dusting, would reveal the fingerprints of Sid Field.

Have you heard Catherine Tate's catchphrase 'How very, very, dare you'? That was an unacknowledged copy of a catchphrase first coined by Sid Field. Have you noticed Russell Brand's grandly mannered Cockney persona? That, once again, is actually a conceit heavily indebted to Sid Field.

Most people, in fact, would be really surprised to find out just how much that is now celebrated as pleasingly clever, playfully camp or refreshingly novel and inventive actually derives from the crafty art of Sid Field. The man was extraordinary. He is British comedy's missing link.

Where did he come from? He was born into a working-class family in Bell Barn Road, Edgbaston, Birmingham, on April Fools' Day in 1904, and brought up in the Sparkbrook area of the city. His father, Albert, was a whip and swagger-cane maker who was also an excellent amateur mimic and storyteller; his mother, Bertha, was a volatile character whose misguided belief that she had a special gift for costume design meant that young Sid was obliged to pose outside their modest house in such dubious outfits as the one that featured an over-sized Norfolk jacket, an Eton collar and a pair of knickerbockers, clutching a silver-mounted cane that came all the way up to his ears.

After impressing his family with his Chaplin-like grace and comedic invention, he began to perform little shows for the neighbours in his back garden. His father was happy just to sit back and enjoy them, whereas his mother, eager to sample the show business life vicariously through her son, started pushing him to audition for a succession of nearby productions.

A local music teacher was so astonished by his precocious talent that she encouraged him to apply for a job with a touring company, the Kino Royal Juveniles, when he was barely twelve years of age. Joining the ensemble in the summer of 1916, and then moving on as a member of such similarly quaint-sounding outfits as the Harry Orchid Toyland Troupe, he gained invaluable experience before starting a solo career, touring the provincial music halls and developing an ever-expanding repertory of vivid comedy characterisations.

What was he like? Physically, he was a tall, rather stocky figure with thick and bouncy brown hair; big mobile eyebrows that arched and flattened like bird wings on the breeze; large and dark saucer-like eyes; a long chubby nose that from the front resembled the cartoon 'Kilroy was Here' snout that drooped over the top of a neighbour's fence; and a mouth with a thin upper lip and a strong lower lip that seemed always in the process of curling up into a conspiratorial smile.

During a performance, however, he was like a strange and special shape-shifter, able to seem, from one sketch to the next, bigger, smaller, slighter or stouter than his real self as he switched between playing lithe and balletic sprites and heavy-footed and hard-knuckled louts, from stiff-backed martinets to slope-shouldered misfits. It was as if, once the spotlight picked him out, his mischievous comic spirit took control of people's sight. Whoever he wanted to be, for as long as he wanted to be them, he was.

What could he do? He created sketches featuring such sharply observed and powerfully effective figures as a sly Cockney spiv, a melancholic drunk, a childlike trainee golfer, a camp portrait photographer, a seedy cinema organist, a cigar-chomping American military officer, a hapless billiards player and a moonstruck musician, usually playing off a sour-faced comedy foil such as Jerry Desmonde (who in turn is now better known for his later, lesser, work as Norman Wisdom's straight-man, the glowering 'Mr Grimsdale').

The script for each sketch might only have stretched over five or six small and liberally-spaced pages, but on stage the routine would last for up to twenty minutes as he grew into the situation, and the character - first reacting to, and then anticipating, and then controlling the audience reactions. Right from the early days of his performing career, he had an instinctive ability for inducing a sense of theatrical intimacy, connecting with those in the auditorium like, many years later, viewers would connect with the close-up contents of a TV screen.

This is why quoting much from a Sid Field sketch would be counter-productive, because it is like translating the performance of a great song stylist into a simple text message. Take, for example, a few lines from the golf sketch:

JERRY: Put the ball down. That's right. Now make the tee.

SID: Make the what?

JERRY: Make the tee.

SID: I thought we were gonna play golf.

JERRY: Well of course we're going to play golf.

SID: Well, why do you talk about making tea for then?

JERRY: No, no! Make the tee with sand!

SID: Pffft! I'm not drinking that stuff!

JERRY: What stuff?

SID: Tea with sand?? Don't be foolhardy! 'Tea with sand'! More like cocoa!

Abandoned on the page, the lines just lie there looking painfully plain, limp and lifeless. The comedy, the magic, comes from the beautiful ingenuity of Field's performance: the childlike innocence, the peculiar vulnerability, the pouty petulance, the vivid verbal colourfulness ('stuff' slips up to reveal a more common-sounding 'sterf,' 'cocoa' strains to recover the prissy affectation as 'coah-coah,' and the self-conscious quaintness of 'foolhardy' is made to sound even camper as 'fooool-haardeh') - it all combines to animate what would otherwise have been flat and static, and make a very simple sketch suddenly seem so rich, so endearing, so amusing and so charmingly watchable.

That is what Sid Field could do. The signs that he could do it were there more or less from the start.

So what did the young Sid Field go on to do? For the best part of thirty years, he did surprisingly little of any consequence.

One reason for this was the fact that, thanks to his naturally diffident personality, he never believed in himself enough to fight for his chance of fame (and, even as a teenager, he had to rely on alcohol to combat his chronic sense of stage fright). While he loved making people laugh, he hated the idea of having to make them laugh, and so any ambition was always undermined by anxiety.

Another reason was that, as he had no interest in, or patience for, the business aspect of show business (he used to stuff away any legal papers deep inside his sock drawer), he left his career in the hands of a succession of dubious characters, who included his increasingly erratic mother, then a gambling-mad manager who only booked him in accordance with the British horse racing calendar, and then another who kept him tied to a hopelessly constrictive long-term provincial contract that lost him countless opportunities of reaching a bigger audience.

The result was that he simply kept touring and toiling his way up and down the circuits of the Midlands and the North of England, year after year, decade after decade, while waiting patiently and vaguely for a career-changing summons to London. Then, eventually and quite suddenly, the call did come, and Sid Field, at the age of thirty-nine, became British comedy's ultimate 'overnight sensation'.

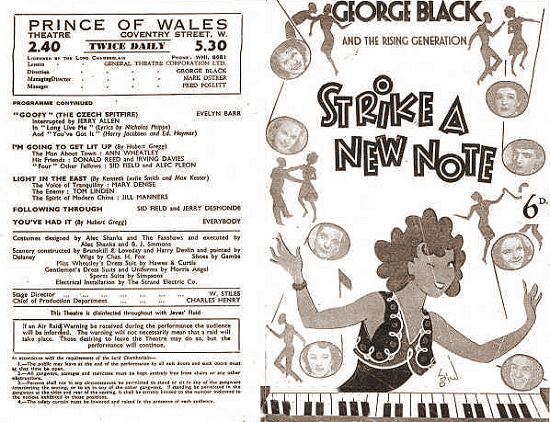

He appeared, as a sort of 'mature student,' in 1943's youth-oriented Strike A New Note (a West End revue whose bill included two impressionable young solo comedians who would later find fame together as Morecambe & Wise). It started out as an egalitarian enterprise - all of the performers were simply billed alphabetically - but it only took a few weeks before the posters had been amended to give star-billing to Sid Field, 'The New Funny-Man' and 'The Biggest Comedy Find In Years'.

'Never before,' one critic would later write of the opening night, 'have I heard such gales of laughter and applause whirling through a theatre as I did on that historic Field-night. The man in front of me laughed so helplessly that he had to be carried out and given first-aid. I, myself, felt weak with mirth. I was sure that every man and woman was longing to shout to the comedian on that stage: "For mercy's sake, stop! You'll kill us with laughter!"'

One of his catchphrases - 'What a performance!' - not only seeped swiftly into the public consciousness, but also seemed to sum up the consensus about his act, as, night after night, the likes of Clark Gable, Jimmy Stewart, Deborah Kerr, James Mason, David Niven and Alfred Hitchcock queued up backstage to offer their congratulations, and politicians such as Churchill and Eisenhower passed on their praise (and in America Time magazine saluted him as 'England's finest pantomimist since Charlie Chaplin'). The show ran for 661 performances, making Sid Field, in the process, the biggest comedy star in Britain.

He followed this huge success with an equally effective West End sequel, Strike It Again, in 1944 (which ran for 438 performances) and then, during 1946-7 (with a young Terry-Thomas in tow) he headlined in the record-breaking Piccadilly Hayride (running for 777 performances).

Once again, the critics celebrated the timeliness of his special talent - 'You'll forget your austerity blues when you see Sid Field' - and his 'indescribably funny' artfulness. 'Mr Field,' wrote one reviewer, 'deserves all his triumphs and the even greater triumphs which are almost sure to follow.'

Once again, his colleagues raved about his remorseless inventiveness: 'Sometimes it took me five minutes to compose myself enough to say my line because Sid made me laugh so much,' Terry-Thomas would say about sharing the stage with him. 'He never stopped ad-libbing. You had no idea what he would come out with.'

He also appeared, after much prodding from his management, as the star of two home-grown movies for the Rank Organisation: a laboured attempt at a lavish Hollywood-style meta-musical revue entitled London Town (which, in spite of its stagey shortcomings, at least showcased some of his most famous sketches) in 1946, and an oxymoronic-sounding 'Cromwellian comedy' called Cardboard Cavalier (in which he co-starred with Margaret Lockwood) in 1949. Neither movie, however, would turn out to be anywhere near as funny as his earlier low-budget effort, That's The Ticket (1940), even though they were subjected to a much harder sell.

As usual, while the critics might have complained about the quality of the productions, they found much to praise about Field's performances, with one claiming that he was 'Britain's only film comedian who succeeds in being funny'. Movies, however, would never be his preferred milieu; he hated the huge and cumbersome cameras ('coming at me like a bloodthirsty dragon'), the repetitive and stop-start nature of filming, the seemingly random re-writing of the scripts, the unnerving silence on the set and the absence of an audience - as well as the poor quality of the projects he was offered - and thus showed no interest in continuing with a big screen career.

He also seemed disinclined to 'make it' in America. Although delighted to have been welcomed there so warmly by so many of his comic heroes (and greeted as a house guest by his ultimate idol Charlie Chaplin), he still felt, as someone who liked to lose himself in multiple roles, ill-suited to a culture in which the top comedians were always expected to impose their own personality on their characters.

Another factor that ensured that his time in California would be cut very short indeed was his own proud and indelible Britishness. A new life in New York and Los Angeles of chronic and restless and strangely humourless competitiveness was simply not meant to be for someone as self-deprecating as Sid. 'I feel so homesick,' he wrote to his wife, 'it isn't true.' He had plenty of offers to stay to work in cabaret, theatre, radio and film, but, to the bemusement of all the agents and impresarios who were queueing to sign him up, he passed politely on each one of them and then flew straight back to London.

He remained most at home in front of a live audience in a theatre, where, as the legendary showman Charles B. Cochran acknowledged, his impact continued to strike even the most seasoned of experts as immense: 'I was unprepared to find a comedian with charm and great originality who caused the greatest laughter I have heard in a theatre for many years, without a questionable joke or gesture and who stood comparison with all the great ones of my crowded memory.'

The critics all continued to adore him. James Agate remarked: 'At last the stage has an actor who knows how to exuberate'. J.B. Priestley declared: 'No comic can ever have had a greater immediate success, going up like a rocket that exploded its gold and silver in the darkness of wartime London'. Kenneth Tynan would enthuse: 'His style was amorphous: he was like a man carrying about with him a number of inexplicable parcels, which he couldn't remember buying, and certainly didn't want. Yet whenever he opened one of them something wildly funny flew out'. This man, the critics agreed, was the greatest comic talent of his generation.

The other comedians all adored him, too, with Bob Hope going so far as to hail him as 'probably the best comedian of them all'. Many in Britain who were at the start of their own careers came to use one or another of his many characterisations as a role model to inspire their own nascent act.

Frankie Howerd, for example, combined the camp fastidiousness of Field's photographer with the blunt bumptiousness of Field's spiv, borrowed some of his catchphrases, and then fashioned a whole new persona; Tony Hancock imitated the way that Field found humour in pomposity, misery and despair; Kenneth Williams adored his sprightly sauciness, as well as his startling versatility, and developed his own skills accordingly; Morecambe & Wise drew on insights gleaned from studying Field's sharply-timed interplay with Jerry Desmonde to develop their own distinctive double act; and Spike Milligan (who said that seeing Sid in action had been 'the first time I had really laughed hysterically at a character on the stage') was inspired to create some similarly droll and quirky creatures for The Goon Show. Field also paved the way for all of those countless comedy actors who wanted to amuse by playing characters in sketches or sitcoms instead of by performing conventional stand-up.

So where did Sid Field, at the peak of his success, go next? He drifted brilliantly.

He bought a bigger house and a better car. He played a great deal of golf. He was a regular in the front row at prize fights ('It helps to relieve my feelings,' he said. 'People are always laughing and screaming at me, but at the ringside it's my turn'). He enjoyed placing plenty of bets (his system involved scribbling each runner's name down on a piece of paper, screwing them all up in his fist, then throwing them on the floor and backing whichever one landed furthest away from his feet). He socialised with the same old group of friends ('You meet a lot of people on the way up,' he said. 'I want them to know me again on the way down'). He also, as an exceptionally kind and caring soul, helped out countless friends, co-workers and even fleeting acquaintances financially, often with no prospect of ever being paid back ('How can I turn people down?' he would ask repeatedly of his exasperated wife Connie. 'I can't say I haven't got it').

In general, while others in his prime position, with his prodigious comic powers, would have pushed themselves remorselessly on, he preferred to sit back and savour each day rather than strive to seize it. 'He seldom made any effort to look for new work,' his wife would say. 'He believed in letting life come to him.'

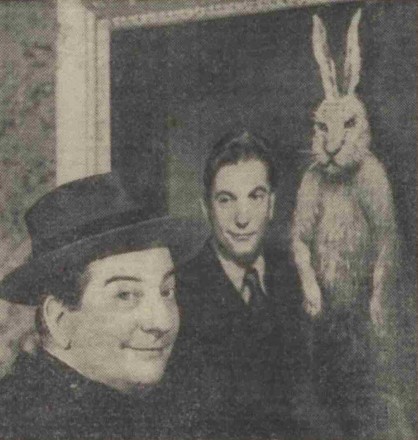

The one last challenge that would excite him was the chance, at the start of 1949, to return to the West End as the star of a new stage production of Harvey as the chronically merry middle-aged bachelor Elwood P. Dowd, who believes he is accompanied everywhere by an invisible 6ft 1½ inch rabbit. Regarded as his first attempt at 'legitimate' acting, the move attracted some intense media attention ('Field's success or failure,' wrote one critic, 'more interested the theatrical profession than any other first-night performance I can remember'), and, once again, he emerged from the test triumphant.

'Mr Field,' one review read, 'suppresses almost entirely (but not quite) the urge of foolery to break through his admirable performance. His smile suffuses a glow of brotherhood and unruffled contentment; he misses no point in the dialogue, and when called on to deliver a sentimental speech proves himself capable of expounding the most pretentious fake-philosophy with a tenderness that hushes the house.'

The actor, broadcaster and playwright Alan Melville was even more positive in his praise: 'In Harvey,' he wrote, 'Sid has shown that he is much more than just a great comic. When you have played in revue at the same theatre for a number of years, and when your mannerisms and catchphrases are known and adored by your fans, it is a tricky assignment to tread the same boards in something entirely different. [...] What pleases Sid most about his present success is that, though the faithful may come to see Sid Field, they stay in their seats seeing Elwood P. Dowd - and, in certain cases, that rabbitty companion of his. Here is a glorious piece of acting in by no means an easy or a cast-iron play. Here, in fact, is more than one expected even from a great comedian, a great friend, and a great person.'

The show (which took £20,000 at the box office - well over a couple of million in today's money - in its first month) would run on throughout the year, and beyond, and so would the many warm plaudits about its star. The royal family went to see him, many members of the Government went to see him, countless of Sid's fellow celebrities went to see him, and a seemingly endless stream of his adoring public went to see him, too. There was, it was generally agreed, no other entertainer in the country who was as respected, admired and loved as this remarkable man.

Then, just as suddenly as he had arrived, Sid Field was gone. After suffering a succession of heart attacks, he died on 3rd February 1950, at the age of just forty-five.

The international show business establishment mourned him publicly and sincerely. 'It is a great loss to the world,' said Bob Hope. 'But it means a lot of happiness in heaven.' Sid's old straight man, Jerry Desmonde, simply said: 'To know him was to love and admire him.' The producer George Black Jnr described him as 'one of the greatest and nicest men who ever walked into a theatre. Success never went to his head. He was the easiest person in the world to handle.' The veteran comic George Robey added: 'He was one of the world's truly great and natural artists. Sid was a born humourist and pantomimist, and very greatly loved by all who had the privilege to know him'. Danny Kaye called him 'a dear and beloved friend,' and said that 'London will not be the same to me, when I return, without Sid,' while Bing Crosby remarked: 'The entertainment world has lost a great artist. It was a pleasure to know him personally. We will all miss him.' Cary Grant, upon hearing the news, simply broke down and burst into tears.

His passing was marked by two memorial services, first in his native Birmingham and then at London's St Martin-in-the-Fields. These were followed in the summer of 1951 by a midnight matinee benefit concert at the London Palladium to raise funds for his wife and three children (one sad consequence of Sid's legendary largesse was that he left considerably less than might otherwise have been expected).

Attended by the likes of the Duchess of Kent and the politician Aneurin Bevan, and featuring Noel Coward, Danny Kaye, Laurence Olivier, Cicely Courtneidge, Douglas Fairbanks Jnr, Orson Welles, John Mills, Richard Attenborough, Jack Hylton, Jack Buchanan, Pat Kirkwood, Margaret Lockwood, Judy Garland, Elizabeth Taylor, Vivien Leigh, Peter Ustinov and Jerry Desmonde, along with most of the country's top comics and more than two hundred other performers, the Palladium event was an extraordinary three hour occasion, with the stars appearing and combining in unexpected ways which anticipated the format of much later shows such as The Secret Policeman's Ball. It would, said one observer, 'be long remembered as the most whole-hearted compliment paid to any British comedian'.

Once the applause had died down, however, there was little that remained except for the memories, and, once those memories started to fade, so, too, did Sid Field. In a culture where, increasingly, the image was coming to matter far more than the word, the paucity of his performances surviving on film meant that the effort to remember Sid Field started to resemble some kind of ancient and obscure act of storytelling.

Without enough archive footage or relevant talking heads, the TV companies were disinclined to make any documentaries. Without (supposedly) enough interviewees or images, and without any dirt or demons to draw in a more youthful demographic, the publishers were similarly unwilling to commission any biographies. It did not take that long, in such circumstances, before some people, having grown up being dazzled by lesser talents, started to ask: 'Sid Who?'

His remaining fans did what they could to bring the real man back into view. An historian called John Fisher, for example, finally managed to produce a well-meaning but somewhat slight biography of him in 1975, and then the actor David Suchet attempted to summon him back to life on the stage in William Humble's patchy 1994 play called What A Performance!.

That, however, was more or less it. By the end of the 20th Century, precious few people still seemed to know that a comedian called Sid Field had ever been around.

The strange neglect has continued into the current century. In 2011, one of Field's few old movies, London Town, was finally released as a DVD by Odeon Entertainment, but without any notable publicity (and it soon ended up being deleted), and then an affectionate if not entirely accurate new TV documentary, David Suchet On Sid Field: Last Of The Music Hall Heroes, was screened to a small audience on BBC Four, but it approached him more as a curious relic from a bygone age than as a continuing influence on contemporary comedy. The real man, and the real legacy, remains at best misunderstood and undervalued or, far more commonly, completely overlooked and ignored.

It thus seems, these days, poignantly ironic that his last significant role should have been in that of Harvey, because Sid Field, slowly but surely, has himself become British comedy's equivalent of Elwood P. Dowd's invisible giant rabbit - impossible to miss, so long as you know that he is there, but otherwise, at best, a seldom-muttered myth.

This is why, seventy years on from his sadly premature death, it would be so good if anyone, from reading this, feels sufficiently curious about this man, who once meant so much to so many, to make some effort to seek him out. Try looking on YouTube, where a few blurry versions of some of his best sketches (such as 'The Photographer' and 'The Golf Sketch') along with a grainy print of The Cardboard Cavalier and the odd tribute clip can still be seen; and explore a few other sources here and there for the odd rarity that has been quietly made available. There is just enough out there, if one really searches, to see, appreciate and share, and stop people from ever again asking: 'Sid Who?'

Sid Field was a genius. Not just another over-hyped, breathlessly press released, post-pub Friday night Channel 4 sort of fleeting faux comedy genius. A real genius. Someone who genuinely took your breath away. Someone who changed the way that others did comedy. Someone who made you smile. Someone who made you care.

That is something, and that is someone, that is always worth remembering. He is no 'Sid Who?' He is the late, great, irrepressible, irreplaceable, and, yes, in spite of it all, unforgettable Sid Field.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out moreLondon Town

Roll up! Roll up! London Town is one of the biggest films ever made in Britain!

Comedy legend Sid Field plays comedian Jerry Sandford who comes to London from the provinces expecting to make his fortune - only to find himself stuck in the wings as the unloved understudy. Determined to help her dad hit the big time, his daughter Peggy (a young Petula Clark) decides to take matters into her own hands.

One of Rank's biggest-budget films, London Town is packed with classic tunes and show-stopping dancing; this gorgeous Technicolor fantasy is effervescent entertainment of the finest vintage!

First released: Monday 19th September 2011

- Distributor: Odeon Entertainment

- Region: 2

- Discs: 1

- Minutes: 122

- Catalogue: ODNF235

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.