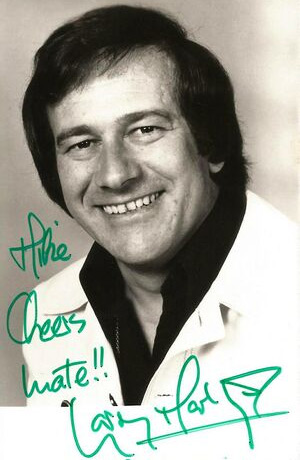

Big dreams, small scenes: The missed hits of Larry Martyn

Few people, in the history of British comedy, must have felt so diminished, as they reflected on the disparity between their dreams and their reality, as Larry Martyn. He was, in his own mind, a star who was set for the spotlight; he was, in our eyes, a supporting player who stepped in and out of the shadows.

If you remember him at all now, it's probably as that character actor who kept popping up, here, there and more or less everywhere, on TV and movies during the Sixties through to the Eighties, usually as a bolshy proletarian type - a cleaner, a cabby, a barman, a builder, a machine operator - or else as a replacement for some or other actor who had either died or departed for another role. Sift through the old sitcoms, sketch shows and soaps from that era, and, sooner or later, you'll find Larry Martyn playing a minor part.

A face rather than a name, he fitted, at least as far as he was concerned, in the 'could have/should have/would have' category of actors who were not so much under-used as ill-used. Frequently visible but rarely left to linger, he felt like a flame that was ready to flare, but was only ever allowed to flicker.

Born in London on 22 March 1934, Lawrence Martyn had seemed made to entertain. As soon as he could talk, he was parroting comedians' catchphrases picked up from listening to the radio; as soon as he could walk, he was up on his feet and ready for visitors, dancing around to attract their attention.

Later on as a child, he became obsessed with the circus. When the Bartram Mills Circus arrived in November 1946 for its first post-war season at London's Olympia, Martyn, then aged twelve and with his family based just a short walk away from the venue, was seated at the ringside, soaking up the experience like a sponge. Having volunteered day after day to do odd jobs backstage, he was eventually allowed to watch all of the shows for free.

He became so addicted to the spectacle that, when the circus moved away from Kensington, Martyn ran away from home and went with it. 'I didn't take anything - not even a change of shirt,' he later said. 'I was so excited that I just didn't think to pack anything'.

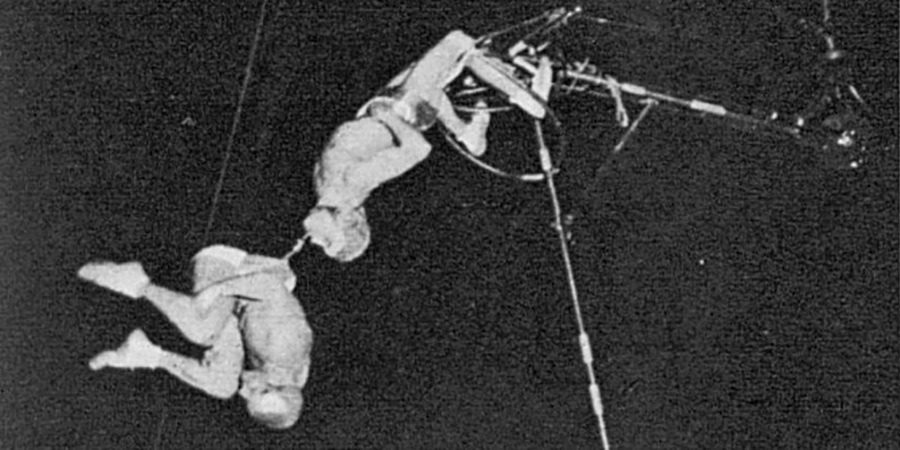

He ended up in Ascot, where there was the headquarters of, amongst other artists, a troupe of French acrobats - two men and a woman, proud ex-members of La Résistance, who were described at the time as being one of the circus's 'most sensational and fearless acts' - called the De Riaz Trio. Thinking him lost and alone, they took him in and started teaching him all of the tricks of the trade, from juggling and somersaults to using the trapeze and waking the high wire.

The climax of their routine involved all of them swinging high above and across the sawdust ring, while a model of a Spitfire aircraft buzzed around them. Young Larry, after some intense training, ended up taking part in a scene that one startled reviewer described as 'the kind of act you cannot look at, but have to'.

He toured with them around England for three months. The idyll only ended when the act was included in the Bank Holiday Fair at Hampton Court, and someone recognised little Larry. His angry but relieved father dragged him crying back home, gave him a good talking-to and then sent him off to school.

Larry, however, was still desperate to escape, and searched the newspapers for any sign as to where his old colleagues might next be appearing nearby. He made friends with another acrobatic team, a Belgian quintet called The Five Bradforts, who invited him to travel with them across Europe performing an act described as 'a kind of spring-mattress-somersaulting affair,' but his father found out and stepped in to block the move.

Larry stayed in school, with deep and demonstrable reluctance, until he reached the age of fifteen, when he raced off to become one of the so-called 'little horrors' in Will Murray's famous troupe of young knockabout entertainers called Casey's Court (whose alumni included Charlie Chaplin and Stan Laurel). It was there that he added to his circus skills by learning how to dance and sing and execute slapstick routines (his technique became so sound that he could even slip over on to his back on a hard stone floor without incurring any injury), so that, after a few months of thorough training and performing, he was competent in more or less any and every area of entertainment.

By the age of sixteen he was touring as a solo act on London's variety circuit, mixing comic patter with some acrobatic routines and ending with a song and dance, and in 1951 he made his first appearance in a professional revue at the Theatre Royal in Stratford East. After two years of performing in front of every conceivable kind of crowd, he felt that he had proven himself as an all-round ready-for-anything entertainer.

Before he could progress any further, however, he was called up for a stint of National Service in the Army, joining the Parachute Regiment. Drawing on his acrobatic skills, and feeding his appetite for adventure, he enjoyed embarking on jumps so much that he would later do them for pleasure as a member of the British Parachute Club.

Once demobbed, he dabbled with London's acting schools, but, after finding what he later termed their 'sausage machine methods' far too constraining, he dug deep into his savings and travelled to New York and Toronto in search of more satisfying sorts of instruction, taking classes not only in acting but also scriptwriting, camera technique and film and television production.

He returned to London in the middle of the 1950s. Full of self-belief and vaulting ambition, he was determined to make his mark in the business as an up-and-coming auteur ('I write about real people and real situations,' he said, as he urged journalists not to stint on the hyphens when describing him in print as an 'actor-writer-singer-director-producer'). He sent scripts and sketched-out ideas to theatre, TV and movie companies with the bold insistence that, if any of them were to be made, he would have to play the lead.

When asked if a humbler approach might perhaps be the more prudent way to get ahead, he shook his head and, with a smile, said he was determined to do it his way. 'I figure,' he said at the time, 'that if you bang on a door long enough someone will answer it'.

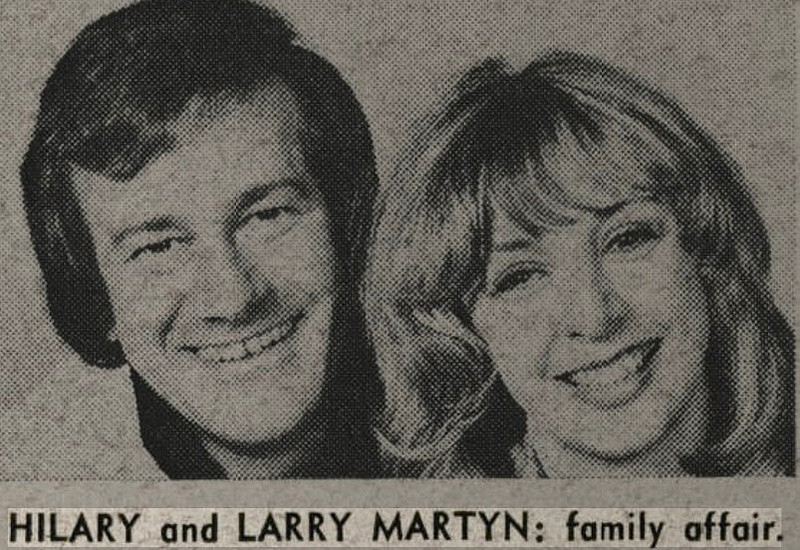

He certainly appeared to be progressing as planned when, in 1957, he paused his increasingly busy schedule to marry his glamorous young girlfriend Hilary (who was six years his junior). Aside from already sharing the same surname of Martyn, they had actually grown up in the same neighbourhood in West Kensington, but had never met until, as adults, he was auditioning as an actor and she as a dancer.

The tabloids were so keen to feature pictures of her that they were happy to also include stories about her life with Larry and their two young children, Deena and Debby, making them, for a while, one of the most familiar and fashionable young families - a budding 'power couple' in today's parlance - in show business. Rarely did a photo opportunity for Hilary go through without some mention of her husband's many plans as a performer, playwright and producer.

Although this undeniably heightened his profile, it did little to broaden the range of offers he was currently receiving. He was starting to get steady work as an actor, appearing fairly regularly in one-off TV plays, but, much to his frustration, his own projects were not being picked up by producers. Some of his friends, sympathising with his sense of being under-appreciated, felt that his all-round proficiency was, perversely, holding him back. As one of them put it, 'he has so much talent that he doesn't know where to direct it'.

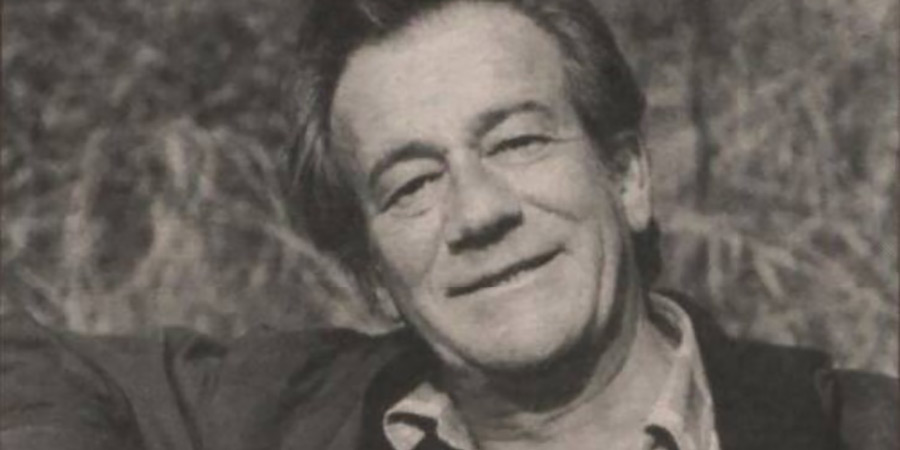

With his dark slick-backed hair, and sharp and broody features, he looked like a British James Dean or a Marlon Brando, tailor-made for the voguish 'angry young man' style of movie, or the gritty kitchen sink TV and theatrical dramas, but he was beaten to all of the best roles in such genres by contemporaries such as Albert Finney, Richard Burton, Tom Courtenay, Alan Bates or even Harry H. Corbett.

Then there was his potential appeal in lighter roles. With his competence at both character and physical comedy, he seemed just as set for the Carry Ons or the Dirk Bogarde Doctor movie series, but once again, at least in their prime, they passed him by.

He would get to play some rebellious figures in the odd low budget B-movie, and play them rather well. In the 1959 Anthony Newley vehicle Idol On Parade, for example, he provided the one vaguely authentic-looking moment when, playing a budding Gene Vincent-style rock-and-roll star, he rehearsed a suitably mean and moody routine.

More seriously, in the 1961 Edgar Wallace drama Partners In Crime, he appeared as the leather-jacketed biker Pete, who steals a gun and is drawn to danger, only to lose his nerve and turn informer. He put in a promising performance, had genuine screen presence, and received encouraging praise from the critics.

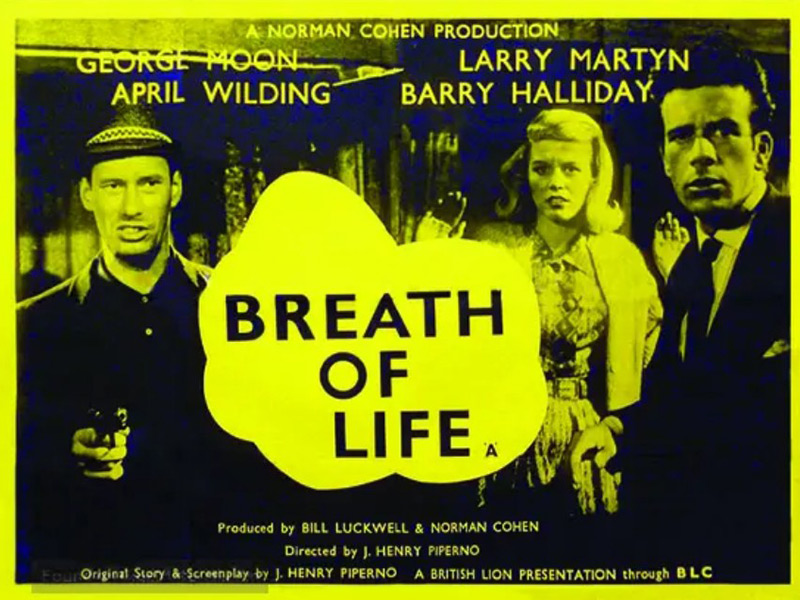

It was much the same with his starring role in the dark and dour 1963 crime story Breath Of Life, which was about 'a bad boy's progression to the gallows via a bank robbery'. 'Martyn,' wrote one reviewer, 'is a young actor worth watching'.

It failed to elevate him, however, to a higher level of status. The big parts, in the best movies, would continue to be out of his reach.

Most of the film and TV programme-makers of the time simply saw him as a handy 'bits and pieces' sort of actor. They knew he could sing, so they would cast him as a skiffle singer; they knew he could dance, so they would cast him as a jive dancer; they knew he could juggle, so they would cast him as a music hall juggler. His versatility made him a useful name to keep on their casting lists, like an acting equivalent of a Swiss army knife tucked away in a kitchen drawer.

Martyn, however, saw himself quite differently. He wanted to build on all of his talents, he wanted to combine them in a context he had created, he wanted to be a star in multiple media.

It would never happen. In spite of his undeniable flexibility, and in spite of the standard of his seldom-matched range of skills, he continued to get offered a fairly narrow set of acting jobs, usually playing variations on low-life criminals, stoical servants, loud-mouthed labourers or testy trade union activists (in order to boost the family income - because many of these roles only demanded a day's pay to be done - he set up a sideline for a while running a second-hand store at Ennersdale Road in Lewisham that promised to 'buy anything that sells').

He sometimes managed to get a more prominent part in a TV play, but it would never lead to bigger and meatier roles on anything even approaching a regular basis. There were, instead, plenty of occasions when, demoralizingly, his characters were only identified in the credits by their behaviour, such as 'argumentative man in washing centre' or 'yob in café'.

Even when, unusually, he got the chance to take part in a comparatively high-profile movie such as The Great St. Trinian's Train Robbery (1966), it was only to play such peripheral figures as, in this case, 'Chips,' one of Frankie Howerd's criminally under-written criminal sidekicks. Although the slapstick sequences promised to make full use of his acrobatic skills, they actually limited him to having an egg smash, along with a fleck or two of flour, into his face, and what few comic lines he was given (when you had fewer things to say than Arthur Mullard, you knew you were in trouble) were largely forgettable.

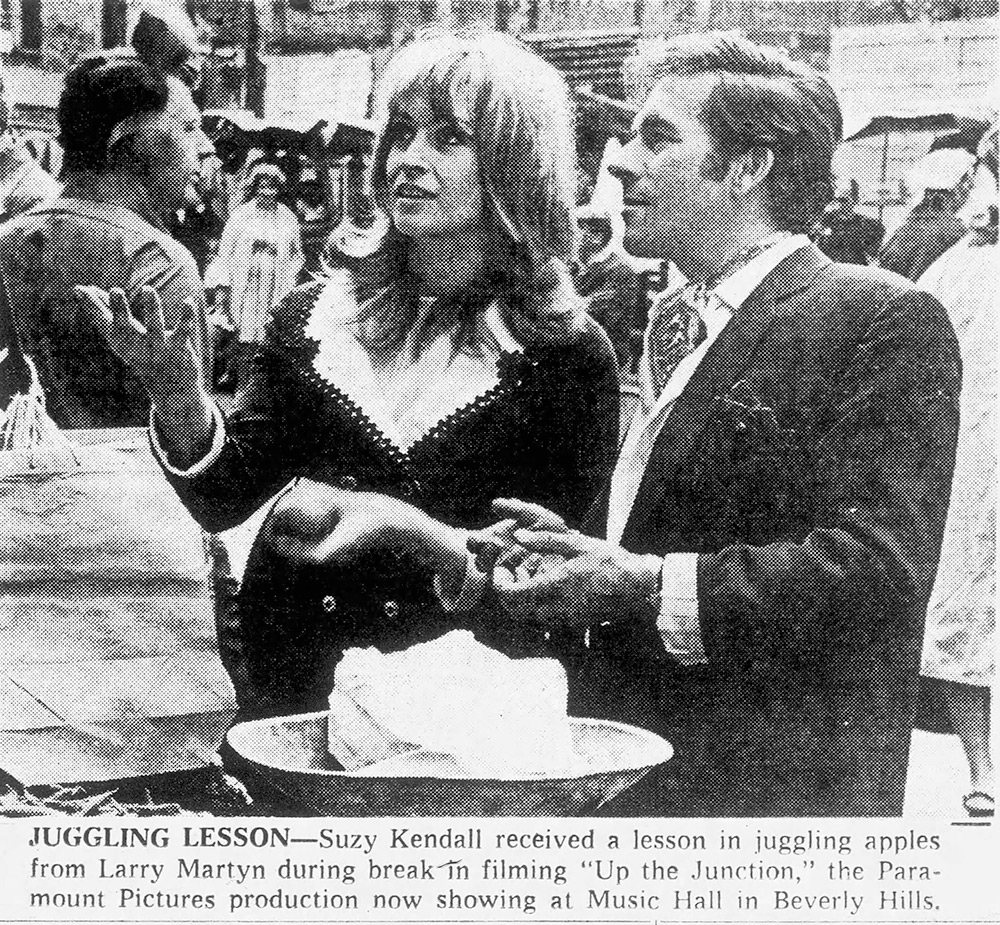

He had even worse luck with Up The Junction (1968), when he not only had to settle for being billed merely as 'Barrow Boy,' but also suffered the indignity of having his surname misspelled in the credits as 'Martin'. Even his sole appearance in the accompanying international publicity pictures only showed him during a break in filming, teaching Suzy Kendall how to juggle apples - which was a shame, because, fleeting though his time on the screen was, he looked, as a flash and flirtatious figure, more assured than several of those who had far more to do.

Throughout this period, he continued to send in his scripts and programme ideas, and work on new fictions and formats, but nothing ever seemed to come from all of his efforts. Whenever he arrived at rehearsals for TV episodes, he would usually hand the producer an A4 envelope containing an outline of a potential series, with a starring role in it, of course, for himself (such opportunism was not that uncommon at the time - Martyn's fellow jobbing actor Jimmy Perry got his Home Guard sitcom accepted via the same unconventional route), but, although there might sometimes be a few words of encouragement, the proposal would go no further.

How much of this was down to bad luck and poor judgement, and how much to too much hope and a degree of delusion? It is hard to say.

We have no access to Martyn's old scripts and screenplays (apart from a reference in an early interview to two of his recurring themes being 'parental neglect' and 'juvenile delinquency'). We have no substantial material with which to evaluate his potential. All that we do know for certain is that he persisted with banging on doors, hoping that someone, somewhere, sometime, would answer one of them.

Disappointed though he was by all the rejections, he could at least take some comfort from the fact that his acting was being appreciated. Throughout the next couple of decades, he was rarely lacking offers of work.

It seemed, indeed, as though he went from one popular TV programme to the next, often only passing through as a one-episode character, but nonetheless doing enough to be noticeable no matter how minor the role might be. He popped up in editions of such drama series as Z Cars; Dixon Of Dock Green; No Hiding Place; The Human Jungle; Man In A Suitcase; The Persuaders!; Crown Court; Upstairs Downstairs; and Department S, as well as countless comedies, such as The Dick Emery Show; Sykes; 6 Dates With Barker; Father, Dear Father; Up Pompeii!; Whoops Baghdad; For The Love Of Ada; The Liver Birds; Look - Mike Yarwood; But Seriously - It's Sheila Hancock; On The Buses; Rising Damp; and The Dawson Watch.

He was one of those performers who amused the rest of the cast as well as the audience. Frankie Howerd, for example, frequently found it hard to keep a straight face when sharing dialogue with Martyn, whose sudden stare, and subtle switch of inflexion, could summon up a laugh that had never been there during rehearsals.

The producer David Croft used him several times for episodes of Dad's Army (and, following the death of James Beck, advised fellow producer John Dyas to pick him to play Private Walker in the second and third of the radio series). He also gave him one of his most prominent roles as the uppity store maintenance man Mr Mash in Are You Being Served?

Mash was a grey-haired and moustachioed little Cockney trade unionist (a distant cousin, perhaps, of Peter Sellers' Fred Kite) who provided the sitcom with its more abrasive moments, such as whenever he clashed with the puffed-up Captain Peacock.

PEACOCK: Just a minute, Mash - you are supposed to use the staff lift.

MASH: Now, look 'ere, Peacock: it ain't even quarter-to-nine!

PEACOCK: 'Captain Peacock' to you!

MASH: And it's 'Mr Mash' to you! Now, you ain't got no authority over me until the official commencement of your employment - which is at nine o'clock. Now, if you come in 'ere early just 'cause your wife can't stand yer, it's no concern of mine - bruvver!

As the all-purpose prick, so to speak, for any pomposity, Mash was also invaluable for the mischievously coarse manner with which he would treat and tease Mrs Slocombe.

MASH: 'Ere we are, Mrs Slocombe: twelve pairs of 30 denier tights - unlucky for some; twelve padded bras - who's kidding who?; and, finally, twenty-four pairs of novelty briefs - known to such common persons as myself as 'naughty knickers'.

SLOCOMBE: What are you talking about, Mr Mash?

MASH: Here - look at that. [He offers up a pair of garish pink panties]

SLOCOMBE: Oh, it's got writing on. [Squinting] What does it say, Miss Brahms?

BRAHMS: 'If you can read this, you're too close'.

SLOCOMBE: How disgusting!

BRAHMS: It's true!

MASH: What about them, then? [He brandishes a pair of panties with a hand print on each cheek]

BRAHMS: Ooh-ohh - randy!

MASH: Then there's these. [He picks up some more] These come in four models: 'Hello, Cheeky'; 'I Love Elvis'; 'Your Flies Are Undone'; and 'No Parking'.

SLOCOMBE: Did you ever see anything like it in your life?

BRAHMS: My boyfriend bought me a pair of those once. But I wouldn't wear them.

SLOCOMBE: What did they say?

BRAHMS: 'In case of emergency, pull down'.

MASH: That must be worth a £5 fine!

SLOCOMBE: That'll be quite enough of that, thank you, Mr Mash! Captain Peacock?

PEACOCK: Are you having trouble, Mrs Slocombe?

SLOCOMBE: I certainly am, Captain Peacock.

PEACOCK: I can only give you a moment - I have to see Mr Rumbold.

SLOCOMBE: I absolutely refuse to display these.

PEACOCK: Well, you're not being asked to wear them, are you?

SLOCOMBE: Certainly not! I wouldn't put them on for a thousand pounds!

MASH: How much would you take them off for, then?

PEACOCK: Mr Mash, get back to your basement!

MASH: Oh, I see - workers not allowed to have a sense of humour, eh? Eh? EH? Cor blimey, it's marvellous! Anyway, mate[i], [i]we have our laughs, don't you worry. You ought to see what they've written about you on the walls of our khazi!

Playing Mr Mash gave Martyn some of the best and most sustained exposure of his career (it also got him the gig - alongside Frank Thornton - of a much-shown road safety public information film, in which his talent for acrobatic pratfalls was, for once, used to good effect), but, following the first three series, he was replaced by Arthur English after making the decision (prompted in part by a longer-than-usual pause in production) to leave for another sitcom, Spring & Autumn.

Broadcast by ITV, the show - which starred Jimmy Jewel as a grouchy old widower called Tommy Butler - afforded Martyn a rather more 'natural' sort of character to play - Tommy's resentful son-in-law Brian Reid - as well as much more screen time. Running for four series between 1972 and 1976, this slow-moving and rather downbeat comedy never reached the kind of large audience that Are You Being Served? continued to enjoy, but, nonetheless, Martyn relished the opportunity to be, for once, somewhere near the centre, rather than closer to the periphery, of the comedy.

Acting opposite the lugubrious but always crafty Jimmy Jewel brought out the best in Martyn, as each competed to steal the scene from the other. Much of their dialogue, focussing on familial strife, could just as easily have been played for dramatic instead of comic effect, which gave their exchanges far more depth than Mr Mash's snappy remarks to the grandees of Grace Brothers.

Martyn probably believed, or at least hoped, that this sense of progression would continue into subsequent projects, but, unfortunately for him, it didn't. After Spring & Autumn ended, he found himself back with the bit parts, having to make the most of under-written characters and precious few lines (one of the oddest of these engagements would see him - after Benny Hill had declined to take the part - play a toreador in a video for Mike Oldfield's downright bizarre single Don Alfonso).

There was occasional work in the theatre, ranging from the darkly dramatic to the lightly comic. Among the ones for which he personally received the best reviews were The Other Fellow's Oats (a farce in which he played a peevish maintenance man) and the Alan Ayckbourn play How The Other Half Loves (as a suspicious spouse).

Some of these productions would prove particularly rewarding because of the fact that he shared the stage with his wife (who was similarly, during those days, drifting through TV engagements, from Crossroads to Within These Walls). More generally, however, that nagging feeling of frustration remained just below the surface, because, in his eyes at least, so much of his talent remained untapped.

It was why he started doing more cabaret, returning to his roots on the provincial circuit with an act that featured stand-up, show business stories, physical humour, impressions, dancing and singing. The venues were usually small and low-key, but he could at least feel appreciated there as an all-round entertainer rather than just a member of the supporting cast. He even agreed to be the warm-up act for the elderly Jack Warner, who was touring the old halls following the end of his long-running series Dixon Of Dock Green, simply because it was another chance to remind himself, as well as everyone else, of the wide range he really had.

As the Eighties began, in spite of all his experience, he was still, as an actor, being offered roles which were identified by their job description instead of their names. In, for example, the TV series Tom, Dick And Harriet (1982) he appeared as 'Buffet Car Attendant'; in Keep It In The Family (also 1982) he was 'Piano Mover'; in The Gentle Touch (1984) he was 'Minicab Driver'; in High & Dry (1987) he was 'Electricity Board Instructor'; and in The Charmer (again in 1987) he was 'Taxi Driver'. He would have been forgiven if, after three decades in the business, he had started thinking to himself: 'Is that all there is?'

The stage musical Barnum, which opened in 1981 and showcased the impressive skills of Michael Crawford (who had been taught the special techniques the role required), must have seemed tailor-made for the circus-trained Martin. Starring roles such as that, however, were quite out of the question for him; his talent, he was often told, was more than big enough, but his name, alas, was just too small.

That always hurt. Those, nonetheless, were the words that would never stop haunting him.

He and his family had moved from London, by this time, to the Kent coast, where he distracted himself, during his quieter periods, by getting involved in local charitable events. One of these, in the village of Dymchurch, would see him dress up as a 17th-century character - drawn from the old local actor Russell Thorndike's Doctor Syn historical novels - for the quaint 'Day of Syn' annual pageant. He was a popular presence at such places, mixing in an easy-going manner with the general public, but in truth, behind the show of bonhomie, the sense of regret had grown sharper.

Some of his last appearances on television would be in the ITV crime drama series The Bill. With sad predictability, the roles - 'Pub Landlord,' 'Landlord,' 'Greengrocer' - received far more from him than they deserved, but perhaps not quite as much as he used to provide. Maybe, at this stage, and on that stage, his dreams had finally given up on him, because he had finally given up on them. The career credits were now so long, but, looking back at them, they had rarely been the ones that he had wanted.

Larry Martyn died, at the age of just sixty, on or about 7th August 1994 at his home at Jefferstone Lane in Old Bakery Close, St. Mary's Bay, Romney Marsh. An inquest - held later that year - judged that the cause of death was 'unascertainable' and an open verdict was recorded.

There was barely any mention in the media either of his death or its aftermath. Like the minor characters that he usually played, the man himself had just slipped away, barely noticed.

He deserved rather more than that. What work he did do, even though it may not have satisfied his own desires, was done well, and quietly enhanced the shows in which it served. The most rich and vivid fictions need not only an engaging foreground, but also an intriguing background, and Martyn was one of those actors who knew, for the latter, how to supply some of those telling little touches.

What work he was denied, on the other hand, he could indeed have done, and one can only sympathise with the frustration he felt about all of those doors that he knocked which always went unanswered. So many dream-driven people may feel that, even after years and years of earnest labour, the most important part of their career remains the one that no one can see, and few felt that so keenly as Larry Martyn.

Help British comedy by becoming a BCG Supporter. Donate and join us in preserving, amplifying and investing in comedy of all forms, from the grass roots up. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more