Those other two fellers: Dick Hills & Sid Green

'I have no spur to prick the sides of my intent,' wrote Shakespeare for Macbeth, 'but only vaulting ambition, which o'erleaps itself and falls on th'other'. Those lines, about the fateful arching of hubris, come to mind when one reflects on the strange shared career of Dick Hills and Sid Green - the two writers who left Morecambe & Wise behind, only to find that the duo they had really left behind was themselves.

Hills and Green, or 'Dick and Sid' as they came to be known, were two of Britain's most successful, and high profile, comedy writers of the 1960s, right up there, as names in their own right, alongside Galton & Simpson. They wrote for some of the biggest names in the business, and some of the biggest shows (and during one especially productive year they wrote no fewer than fifty-two half-hour programmes for ITV), and their enduring association with Eric and Ernie looked set to take them to even greater heights into the next decade. Then, abruptly and very acrimoniously, they decided they would be better off going it alone, and in doing so they ended up going it alone into relative obscurity.

They never expected such a bad thing to happen to them. They had always expected good things to happen to them.

Both of them came from comfortable southern middle-class backgrounds. Richard Michael Hills was born in 1926, and Sidney Charles Green in 1928. Both were educated at Haberdasher's Aske's Hatcham grammar school in south-east London, both became school captains, and both were expected to flourish in their future professions.

Both rose to the rank of officer during the Second World War (Hills in the Navy, Green in the Army), and both of them, in peace time, returned to live and work in London (Hills, after studying for a degree at Magdalene College, Cambridge, went back to Haberdasher's Aske's to teach English, Latin and French; Sid, a more restless soul, had spells in the iron-ore business, ICI and a furniture company).

They were reunited, and came to find their shared vocation, in the late 1940s, when both of them started playing in their spare time for their former school's rugby union side (Dick was a particularly keen amateur player, winning twenty-one caps for Kent, and he and Sid would be the prime movers in organising for floodlights to be installed at their local ground). One rose-gold-tinted early autumn evening after a game, while socialising over a few beers, they decided to combine to write that year's Old Askean Dramatic Society Christmas pantomime.

Encouraged by the positive reaction to their efforts from their fellow alumni, they agreed to keep working together during their leisure hours. Meeting regularly for writing sessions at a Forest Hill coffee shop, they started sending in sample scripts to the BBC. 'Nothing happened,' Sid later recalled. '[But] we kept trying - my conceit told me while watching other people's TV sets that I could write better'.

Eventually, after enduring many rejections, they had some work accepted by Dave King. One of the rising stars of British television, King was a young comedian, actor and singer who was currently being courted both by the BBC and the newly-formed commercial channels. Hills and Green went backstage to see him after a performance at London's Adelphi Theatre in 1955, informed him that they were 'very good writers,' and King was sufficiently impressed to insist on them being signed up for his next series.

The Dave King Show (made for the BBC by the future Morecambe & Wise producer/director Ernest Maxin) would run for two years, and was popular enough to win the writers plenty of press coverage for their contribution to its success. Aside from their continuing association with King, they also started supplying material for Jimmy Jewel and Ben Warriss (who taught them all of the basics about shaping routines for comedy double acts), Jon Pertwee, Eamonn Andrews, Ronnie Corbett, Roy Castle, Dora Bryan and Charlie Drake.

It was primarily King's fast-rising stature, however, that helped lift them to more lucrative levels of employment. When the comedian was hired by American television in 1959 for his own show on NBC, he took Hills and Green with him as his regular writers, and used them again back in Britain for the various shows and specials that he made for ATV. By the start of the 1960s, as a consequence, they had become two of the best-paid, and most in-demand, comedy writers in the business.

Their working dynamic was already very settled and highly effective. Hills, Green would later say, 'was the engine room of our partnership'. Green, typically, was the dominant one for coming up with funny lines and ideas, while Hills dominated the editing process, dropping any element that he felt would not make sense to the average viewer, and demanding that what already worked was made to work even better.

'He would rein me in,' Green reflected, 'until the piece became practical. His strength in comedy was that anything made him laugh - wit, slapstick, mime, vaudeville - his only stipulation was that it should be done well'.

Thanks to their relatively privileged upbringing and education, self-confidence was never a problem for the pair of them. Their middle-class identity was reflected in the way that they signed their scripts - it was always 'S.C. Green and R.M. Hills,' suggesting a pair of stiff-collared solicitors rather than a couple of humble comedy hacks - and their attitude to performers was also somewhat haughty. 'If they deliver the goods,' Hills said sniffily, 'I'll tolerate them'.

They certainly had no doubts as to what the proper pecking order ought to be. 'Don't book the stars and ask writers to find ideas for them,' they said. 'Rather, get scripts from writers and find artists who are right for the formula'.

A sign of the sureness of their ambition came at the start of the Sixties when they worked with Anthony Newley on The Strange World Of Gurney Slade. The La Nausée of the sitcom world, it was an extraordinarily audacious deconstruction of television conventions in which Newley's character walked out of a studio recording and into an existential crisis, talking to trees and rabbits and dustbins and dogs and cows and scarecrows as he tried to make sense of who or what or why he was.

Beautifully photographed and full of fascinatingly dreamlike, yet often superficially prosaic, settings and situations, it was one of the brightest and bravest contributions to mainstream British television that had so far been attempted (and would thus prove inspirational to such kindred artistic spirits as Dennis Potter, Patrick McGoohan and David Bowie). 'People will either love it or hate it,' Newley admitted shortly before the first episode was transmitted. 'There's no middle way'.

Sure enough, slipped initially by ATV into a slot usually reserved for very conventional and crowd-pleasing sitcoms and variety shows, and then (in response to its poor ratings - it lost four million of its audience after its first week) shifted to a 'graveyard' spot, it left many viewers and critics confused and bemused, although the reception was by no means as negative as has often been claimed (The Daily Herald, for example, declared that the show felt like 'a refreshing cold shower after the tepidity' of the usual peak time output, and The People praised it as a much-needed antidote to TV's tendency to encourage 'a nation of automaton belly-laughers,' while The Stage hailed it as 'so clever, so fresh, so stimulating,' as well as 'the best thing that [Hills and Green] have done'). What it certainly did, at least within the industry, was to further enhance the reputation of the writers as two of the most versatile, intelligent and interesting figures in the business.

It would be their collaboration with Morecambe & Wise, however, that would really cement their status as one of television's pre-eminent scriptwriting teams. Starting in 1961, their show would run for six series on ATV, as well as spawning two record albums (Mr Morecambe Meets Mr Wise, 1964; and An Evening With Ernie Wise At Eric Morecambe's Place, 1966), and three spin-off movies (The Intelligence Men, 1965; That Riviera Touch, 1966; and The Magnificent Two, 1967), making Morecambe & Wise the most popular comedy double act in Britain.

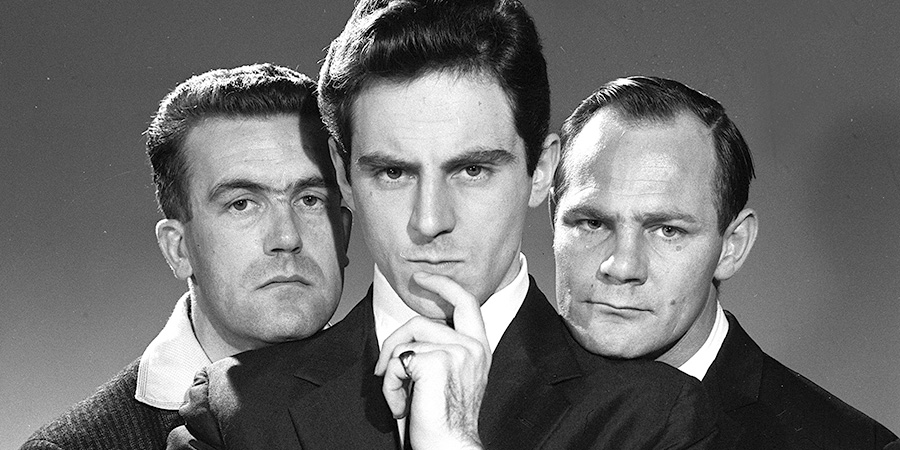

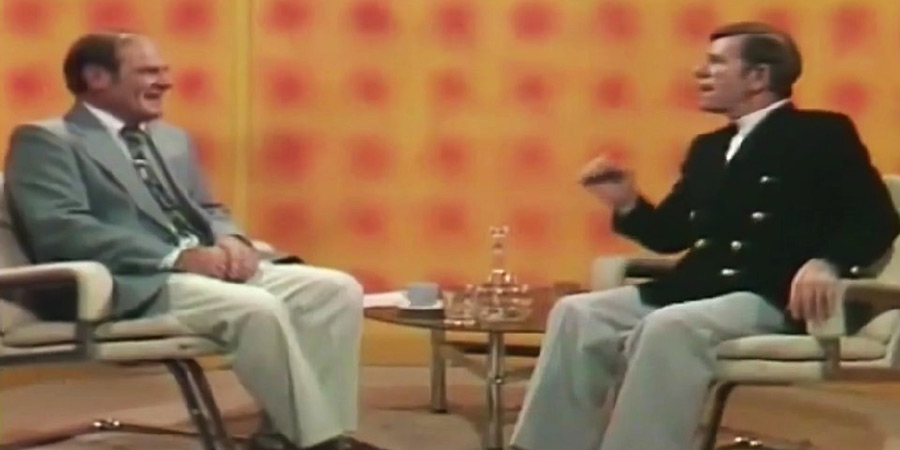

It also made Hills (the short, pudgy, puckish one) and Green (the tall, thin, slightly queasy-looking one) the most visible writing double act in the country, because a feature of the show (prompted by an Equity strike and the subsequent inability to hire any 'proper' supporting players) was their own involvement, on the screen, in many of the sketches. It would be Eric and Ernie, the two polished professional performers, playing off Sid and Dick, the two nervously smirking amateurs, and many of the laughs to be had came from the frequent sight of Sid and Dick 'corpsing' under mounting pressure from Eric and Ernie.

In their hugely popular 'Boom Oo Yata-Ta-Ta' routine, for example, in which Dick ('He's a boomer') and Sid ('He's an Oo-er') joined Eric and Ernie for a musical number, part of its appeal was the palpable sense that the writers' composure was hanging by a thread throughout the performance. Dick, as usual, struggled to contain a smile right from the start ('He's a happy little chap, isn't he?' Eric keeps observing with obvious relish), while Sid's self-preserving attempt at sad-faced woodenness was repeatedly wrecked by Eric's ongoing commentary on his ineptness (ERNIE: 'Give 'em an Ooh, Sid'. SID: 'Ooh'. ERIC: 'You didn't want the part with that, did you!').

This accidental quartet always looked to be having a great deal of fun in these shows, and, to an extent, that was true - but the public pose told only part of the story. While the relationship between the two pairs would stay broadly friendly and playful behind the scenes, there would also be, as time went on, a certain 'edge' creeping in to the connection. Part of this had to do with class.

Eric and Ernie were from the northern working-class. Sid and Dick were from the southern middle-class. Grateful initially to be supported by two such accomplished scriptwriters, the two comedians were happy enough to defer to them - 'They were very talented guys,' Eric would say, 'better educated than the pair of us' - but, as Eric and Ernie grew in confidence, they came to quietly resent the air of superiority that their writers continued to exude in their presence.

This tension gradually grew more intense through the very creative partnership that the two duos shared. While it looked to outsiders, as the credits rolled, as though Hills and Green were solely responsible for the scripts and Morecambe and Wise for the performances, the reality, increasingly, was much more complicated, and contentious, than that.

Hills and Green, in fact, had never been the most conventional of scriptwriters, in the sense that, rather than sit down and grind out all of the material between the two of them on a typewriter, and then deliver it as a complete and coherent text, they preferred a far more fluid and informal process that saw them piece together a script through the interaction they had with their performers.

With Dave King, for example, it had always been more of a collaboration than the formal credits suggested. 'If I have an idea, they work on it,' King said. 'If they get an idea, I work on it'.

It was much the same with The Morecambe & Wise Show. The difference was that, by this stage, Hills and Green, basking in all the praise they were getting, were disinclined to allow their stars to take any of the credit - informally or otherwise.

Neither Eric nor Emie was particularly pleased, for example, when, after their combined efforts had made the show one of the biggest hits of the time, their writers took to boasting to interviewers: 'We can devise a Morecambe and Wise script as we pass in opposite directions on a Tube escalator'. The reality was that they could only devise a Morecambe and Wise script with plenty of help from Morecambe and Wise.

It rankled with Eric and Ernie that their input as performers never seemed to be fully appreciated. As Ernie would recall: 'Sid and Dick might say, "Look, we wrote a perfectly funny gag which got lots of laughs in rehearsal but you ruined it by doing such and such a thing". We would counter that by saying, "It was only thanks to us that the gag managed to raise a smile. It was a weak idea in the first place which we managed to rescue by delivering it in such and such a way"'.

Eric's relentless on-screen teasing of Sid and Dick - or 'Sick' and 'Did' as he sometimes styled them ('He made a right mess of that, didn't he?') - became one way of reminding the writers of who was the real comic powerhouse of the production. Every lofty put-down they had been guilty of during the week in rehearsals would thus receive some stinging payback at the weekend during recordings.

It still took a lot, nonetheless, to shake their sense of superiority. If ever there was an occasion when one or the other (especially the still somewhat schoolmasterly Dick) could show off their superior education at Eric and Ernie's expense, they rarely resisted the temptation to do so.

It rankled even more that Morecambe and Wise's input as writers seemed to be ignored. Each script, after all, was always the result of four heads, not two.

They were more like a group of musicians developing songs out of collective jam sessions, rather than two active writers handing over fully-formed sketches to a pair of passive performers. Indeed, when Eddie Braben later took over the responsibility of supplying the double act with comic material, they were initially astounded to be handed a complete script for each entire show ('But you've got: "ERIC: a line, ERNIE: a line, ERIC: a line, ERNIE:..."' they gasped. 'We've never worked like that before'). Back in the days of Hills and Green, each sketch tended to take shape through far more of a free-for-all.

The process began each week with Morecambe and Wise turning up bright and early at the rehearsal room and talking-through some of their own comic ideas. They might have a couple of situations and some basic dialogue already sketched out, along with some suggestions for other routines they wanted to start improvising, as well as (drawing on the detailed notebooks they had been compiling ever since their early touring years in the Fifties) one or two other pieces that they felt now had the potential to be updated and extended.

Dick Hills would then arrive on his own at ten o'clock in the morning (Sid Green was invariably half an hour or so late with what Eric and Ernie referred to as 'a touch of the domestics') clutching a single piece of A4 paper that bore the title: 'Our Ideas for the Week'. The actual script, Eric Morecambe later recalled, was then produced by all four of them 'collectively ad-libbing around [the basic ideas] while a girl took the gags down, the draft was rushed out, polished and finally rehearsed'.

'We consider ourselves visual writers,' Dick would say by way of an explanation for their unorthodox approach. 'There is not a great deal of dialogue in our scripts, but a great deal of "acting" directions'.

The real (or at least the primary) drivers of the dialogue were usually Morecambe and Wise. They tended to be the ones, during the planning stages, who often did the most to cultivate each concept so that it came alive for them to perform.

These sessions, according to Ernie Wise, were 'full of laughs and good humour but not without their tensions'. Tempers would sometimes flare when proceedings were interrupted by the late arrival of a morose-looking Sid Green, who would shamble in clutching a cup of tea, slump into a chair and launch more or less immediately into a swingeing critique of whatever the other three had managed to come up with in his absence. Eric Morecambe, in particular, would respond to this affront with a few sharply sarcastic remarks of his own.

Eric and Ernie's sense of resentment grew even worse when Hills and Green started getting distracted by other, often more lucrative, writing jobs, leaving the two comedians, more and more, to take up the scriptwriting slack (unofficially, of course) in their absence. There were Hills and Green-scripted shows or stand-up spots for Bruce Forsyth, Harry Secombe, Millicent Martin, Roy Castle, Arthur Askey, Ted Ray, Sid James, Dora Bryan, Bernard Cribbins, Norman Vaughan, Bob Monkhouse and Frankie Howerd, plus the storyline for Carry On Cabby, and (exploiting the popularity of their endearingly clumsy performances with Eric and Ernie) they even had a couple of series of their own - That Show in 1964, followed by Those Two Fellers in 1967 - on the screen.

They were also talking more and more in interviews about the plans they were developing for conquering other areas of show business. 'We want to do a stage musical,' Sid told one reporter. 'Doing the lot - songs as well. I can't read a note. Then neither could Irving Berlin. Music has always been my first love. I've got three halves of musicals written already. Films and TV are fine, but just one successful musical and you can retire'.

They were indeed now so busy that they seldom had the time to appear together at the same place at the same time, preferring instead to divide up their daily duties between them, with Dick spending one day attending rehearsals with various stars in Teddington while Sid made an appearance with Eric and Ernie at Elstree, and then the two swapped locations the following day. Morecambe and Wise, as a consequence, were sometimes made to feel as though they had been abandoned to develop their material themselves, while Hills or Green came in occasionally like a teacher checking on the progress of a class left to complete a task.

An example of this - and the problems it would engender - was the now-famous Grieg Piano Concerto routine. Conceived in essence by Eric and Ernie several years before, and built up initially during their 'unsupervised' sessions, it was subsequently worked on by all four members of the team, and performed both on TV and for an album, but never entirely to the satisfaction of any of them.

Morecambe and Wise's later return to revise (and greatly improve) this source material, with the brilliant additional input of Eddie Braben, has been discussed in some detail elsewhere. What is much less well known is that Hills and Green would go back to it, too, for a Bruce Forsyth show in December 1965 (a much more slapstick and one-dimensional version - staged, incidentally, without seeking Eric and Ernie's permission - that featured Forsyth as the uncontrollable pianist and Jack Douglas as the pompous conductor).

What later enraged Eric and Ernie was the widespread belief, apparently encouraged by Hills and Green, that the original sketch had simply been handed to them, fully formed, by their writers. The truth, as all of them knew, was quite different.

The four of them, nonetheless, stayed together as a team, with more positive than negative moments, until the end of 1968, after Eric and Ernie had moved over to the BBC. They all worked on the first series there together, and - although their new producer/director, John Ammonds, had been fairly unimpressed not only by what he considered to be their insufficiently disciplined approach to shaping their scripts, but also the arrogance that they showed towards their two stars - the assumption was that Hills and Green would remain by Morecambe and Wise's side.

Then came what Eric and Ernie would regard as the great betrayal.

In November 1968, the duo were coming to the end of a lucrative but exhausting week of midnight performances at the Variety Club in Batley, West Yorkshire, when Eric suffered a massive heart attack. The BBC was quick to make it clear that it would wait patiently for the comedian to recover, but rumours were already in circulation that he might never be well enough to resume his partnership with Ernie.

Two people who were quick to reach their own conclusion, it seems, were Hills and Green. First of all, having sent the ailing Eric a supportive-sounding telegram ('This isn't in the script. You must stop this ad-libbing!'), they instructed their agent, Roger Hancock, to warn Bill Cotton at the BBC that they would not sit back and wait for any further news to come through unless they were assured of being made executive producers of the next Morecambe and Wise series (already resentful of Eric and Ernie's new alliance with John Ammonds, they were determined to reclaim some of their old power). Then, when Hancock informed them that Cotton would not countenance such a move, they simply decided, in March 1969, to jump ship.

Neither Morecambe nor Wise would discover what had happened from the writers themselves. The first either of them heard of it was by reading the newspapers.

Eric, who was still convalescing, was profoundly hurt by the manner of their leaving. As his wife, Joan, would tell me: 'In fact, I was surprised just how hurt he was, and I believe that was because of the manner in which it was done. I know Sid and Dick didn't mean any harm: they didn't see it as being underhand in any way. But after all those years of working together, Eric and Emie heard about it third-hand. That hurt. And Eric, I know, thought that Sid and Dick didn't think he could ever return to full strength after his heart attack and were writing him off'.

Ernie (who had been on a plane bound for Barbados when the chief steward brought him the news) was similarly shaken by the suddenness of the split. 'I thought that was the end of Morecambe and Wise, to be honest,' he would say.

Eventually, however, Eric and Ernie would return to work, and become newly-inspired by the arrival of Eddie Braben as their new scriptwriter (a fellow working-class northerner who understood them, and appreciated them, far more than his predecessors ever did). One very telling sign of the new era for them and their show was the change to the credits - which they had insisted upon in their revised contract - which finally acknowledged the input that Sid and Dick had always seemed happy enough to deny: 'Additional material by Morecambe and Wise'.

Hills and Green, meanwhile, remained confident that they were moving on to better things. It was a belief of which they would soon be rudely disabused.

A new show, written by and starring themselves, had been in the offing at ATV (with whom they had just signed an exclusive contract). ATV, however, ended up passing on the project.

They did work briefly with Frankie Howerd (for the one-off Frankie Howerd At The Poco A Poco, followed by a series, The Frankie Howerd Show - both screened in 1969) - which proved awkward for the star, seeing as he was personally very close to Morecambe and Wise - and their old friend Dave King (The Dave King Show - also broadcast in 1969) - which would have been easier but for the recent decline in his popularity.

It soon became clear, however, that none of the exciting new projects that ATV had promised them (ranging right across the entertainment spectrum, from sitcoms to game shows and musicals), nor their supposedly guaranteed increase in power (they had been signed up as producers as well as writers) showed any imminent signs of materialising. By the end of the year they had sold a job lot of their old Morecambe and Wise routines to the Dutch double act of Johnny and Ryk (which further irritated Eric and Ernie, who received no cut for their own 'unofficial' contributions), and were re-evaluating their future.

They decided to relocate to America in 1970 and started writing for The Don Knotts Show - a variety-oriented vehicle for the eponymous comedy actor - only to see the series cancelled after its audience figures rapidly declined. A few other stateside engagements followed, including a Bill Cosby special and another set of variety shows hosted by Flip Wilson, but they were now merely one of several writing teams contributing material, and had no opportunity to stamp their signature on such projects.

Financially, they had never been so well-rewarded for their labours, and they could have continued living in luxury merely by furnishing material for various visiting stars' lucrative Las Vegas appearances. Creatively, however, their years in America grew increasingly frustrating, as a succession of attempts to shape something more meaningful failed to get the green light. Having considered themselves comedy auteurs back in Britain, they were now being treated like humble hacks, and it hurt.

They broke up, entirely amicably, in 1974, when Dick returned to England with his wife Pamela and their three young sons (mainly due to the fact that, with the war in Vietnam still dragging on, his children would soon be liable for the draft, but also because he had grown disenchanted with the fact that, in US television, 'the deal has become the show'). Sid stayed on in Los Angeles for a while, writing gags for the celebrated talk show host Johnny Carson, until, three years later, he decided, with his wife Margaret and their three daughters, to go home as well.

Each of them continued to be very busy as a solo writer. Hills contributed material for shows featuring Tommy Cooper, Jimmy Tarbuck, Bruce Forsyth, Mike Yarwood, Marti Caine, Ted Rogers, Bill Maynard, Mike Reid, Billy Dainty, Tom O'Connor, Russ Abbot and Jasper Carrott, and also hosted the nostalgic chat show Tell Me Another (1976-9) and devised and wrote a children's educational sci-fi series called Captain Zep - Space Detective (1983-4).

Green created and scripted Mixed Blessings (1978-80) - a relatively progressive sitcom for the time about an inter-racial marriage - and also wrote regularly for Cannon & Ball, Pam Ayres, Freddie Starr, Michael Barrymore and The Krankies, as well as being a very popular after-dinner speaker.

The two men, and their families, would remain very close for the rest of their lives ('we never had one quarrel'), and Sid and Dick would often meet up for a meal, a game of golf or an Old Askean reunion. They actually started writing together again, on and off, in 1988, producing a pilot script for a proposed series they called Trio Comedy Theatre, as well as an idea for a sitcom, but this time their joint efforts came to naught. There was no bitterness about the extraordinary success that Morecambe and Wise had gone on to achieve without them, although there were, perhaps, one or two discreetly expressed regrets.

Dick Hills died, aged seventy, in Chichester, Sussex, on 6 June 1996; Sid Green died, aged seventy-one, in Frinton-on-Sea, Essex, on 15 March 1999. It was a pity, for themselves more than anyone else, that the combination of their ambition and sense of self-worth sometimes contrived to ambush their ongoing achievements, because their contribution to British comedy - even if it was not always quite so self-sufficient nor as singularly-styled as they sometimes suggested - is well worth recovering and remembering.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more