Lost Balls: When British comedy went golf mad

There used to be few things more frightening for television viewers than the sight of a comedian in a Pringle sweater. It meant that he was almost certainly about to talk about golf, tell jokes about golf, take part in a sketch about golf or introduce another Pringle-sweatered great mate who was equally mad about golf.

It was one of the strangest things about British TV in those pre-sports channel days: those who didn't much care for golf could easily avoid what little of it was offered in terms of formal tournament coverage, but really struggled to escape from it in the comedy shows of the time. Indeed, one half expected stand-up comics to start coming out on to the stage with a caddy at their side ('I'm aiming for a medium-sized chuckle'. 'In that case I'd suggest a mother-in law lob wedge').

It should not have been such a surprise, when this sort of thing started landing with a horrible thud in the freshly-raked bunker of light entertainment during the early 1970s, because, in truth, comedy's connections with golf went back a very long way. As far as comic literature was concerned, for example, those who disagreed with the claim that the game was 'a good walk spoiled' could point with pride at least as far back as 1921, when PG Wodehouse wrote the first (The Clicking of Cuthbert) of what would be a long and very entertaining series of stories about the sport that he called 'the Great Mystery'.

Lovers of comedy on the stage and screen could invoke a similarly venerable tradition stretching back to the pre-war era of such passionate pitchers and putters as Bob Hope and Bing Crosby in Hollywood, and, over here, the likes of Sir Harry Lauder and Sir George Robey.

The sport also figured in countless stage routines, such as Sid Field's famous golfing sketch, Harry Tate's W.C. Fields-influenced golf specialist vignettes and several Crazy Gang performances, as well as serving as an ingredient in various stand-ups' material, ranging from the occasional Max Miller gag to innumerable Ted Ray stories.

There have, of course, been other sporting interests that have, at various times and for various periods, held some attraction for the comedy community. Horse racing, for instance, was a particular passion during the 1950s for such performers as Sidney James, Charlie Drake, Jimmy Clitheroe, Robert Morley, Wilfrid Hyde-White, Leslie Phillips, Max Bygraves, Chesney Allen, Ronald Shiner, Jimmy Edwards, Al Read and Terry-Thomas (who even campaigned to get horse jumps installed in Hyde Park), and some of them not only watched but also rode (George Formby, a former stable apprentice, actually took part in the odd competitive race as well as organised charity equestrian events for himself and his fellow comics).

Football and cricket seemed to exert an especially strong appeal during the 1960s. Both sports were represented enthusiastically by comic-heavy celebrity teams.

Tony Hancock captained a cricket team that featured his younger brother Roger, John Le Mesurier, Bill Kerr, Sidney James, Eric Sykes (wicketkeeper) and the Australian actor Vincent Ball, along with whatever other comics happened to be available to make up the lower order. Hancock, a very enthusiastic amateur player, would open the bowling and usually stride on to bat at the fall of the third wicket. He and his team would tour the country playing one day games for charity, normally against small village green-style cricket clubs strengthened by one or two famous professionals, and enjoyed some very competitive games.

Le Mesurier, having been coached by ex-pros into being an elegant stroke-maker while at Sherborne and then, in his early adult years, batted stoutly for the Gentlemen of Suffolk, was supposed to be Hancock's principal run-getter, but his habit of preparing for each of his innings by imbibing a beer while puffing away on a 'herbal' cigarette sometimes meant that, following a rash Gower-like waft outside the off stump, it was left to Hancock himself to lead the belated chase of the target. The squad was later strengthened by Le Mesurier's future Dad's Army colleague and Hancock's own TV warm-up man of the time, Bill Pertwee - a cricketing all-rounder who had once been judged good enough to have played the game at county level.

Other celebrity cricket teams sprang up during the decade, proving particularly popular in coastal areas during summer seasons. They were usually one-off affairs, made up of whomever happened to be based at each resort that year, but, once again, they attracted a fair number of comics who were either eager for distraction or else a different means of public exposure (when their teammates were batting, there were plenty of opportunities to sneak off and entertain the crowd).

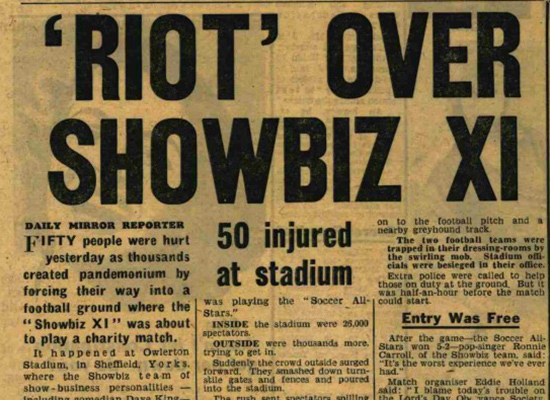

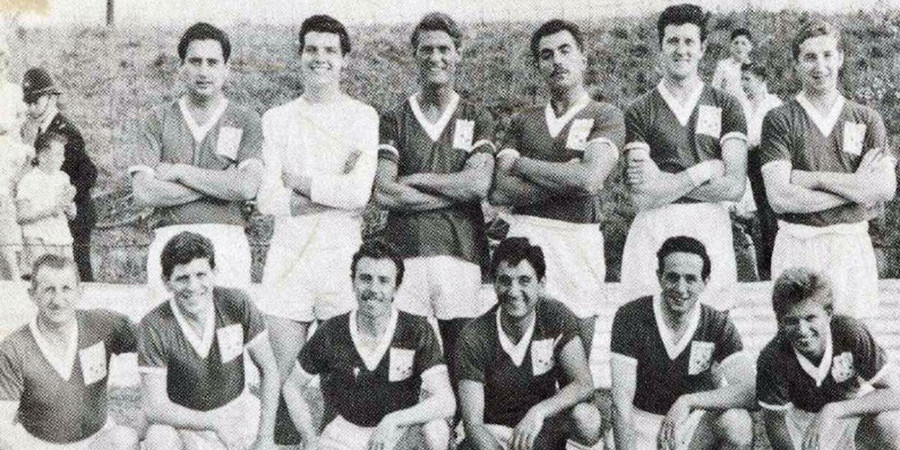

There were even more comedians to be found in the celebrity football teams of the time. The Showbiz XI - founded in the late Fifties by the song plugger Jimmy Henney and Cliff Richard's manager, Franklyn Boyd - was a magnet for many comics throughout the 1960s. Organised in a surprisingly professional manner - they trained at the conveniently-situated Loftus Road facilities of Queens Park Rangers in Shepherd's Bush - the team's regulars included the nippy ex-Northampton Town reserve Des O'Connor, Dave King (who was so fanatical that he would fly back to Britain from America, where he often worked, purely to play in a game), Stan Stennett, Tommy Steele and Mike & Bernie Winters, as well as the former Nottingham Forest trialist David Frost, the movie star and former Bonnyigg Rose right winger Sean Connery, the uncompromising centre back Patrick McGoohan, the proto libero Bill Cotton Jnr and the goal-hanging tribute act that was the gangling disc jockey Pete Murray.

Curiously enough, the games soon seemed to drain the entertainers of any desire to entertain. 'We tried comedy football,' said the crooner, part-time keeper and sometime captain Jess Conrad, 'which was a disaster, throwing buckets of water over people, silly hats, but people never ever came to see that, what they came to see was a football match at a reasonable standard'. The general air of seriousness was also encouraged by the no-nonsense ex-pros who were also on show - a deliberately ill-timed 'reducer' on, say, a gurning Bernie Winters was usually enough to ensure that any 'funny business' was kept to the absolute minimum.

At its peak the team was playing at some of the top footballing stadia in the country, in front of crowds as large as 30,000 (with the matches sometimes being televised), and was in demand for major testimonial games as well as all kinds of charitable causes.

A symbiotic relationship between the professional game and the showbusiness set was developing, as the players came to enjoy mixing with well-known entertainers, and the performers relished the chance to share a pitch with some of the top pros. Gradually, however, ideological differences would start to creep into the celebrity dressing room, and the Showbiz XI would eventually be hit by a bitter split that would result in a rival operation being formed by the Winter brothers.

Mike and Bernie were avid football fans (they would even attempt, in 1967, to lead a takeover of Aston Villa) who had always been among the most enthusiastic members of the club, always making themselves available for selection each Sunday no matter what their professional commitments might have been, but their stubborn refusal to stop being 'comical' while out on the pitch had always riled their more serious teammates. The sight of someone 'having a word' with one or other of the Winter brothers had been a common sight for some time. Something had to give, and, eventually, it did.

On one occasion, when Mike and Bernie were appearing in pantomime in Bournemouth, they braved a blizzard to drive more than a hundred miles to play a game in a tiny town in Bedfordshire. The following week, however, they again battled the inclement weather and travelled to Ruislip, reeking of wintergreen, only to discover that they had been dropped from the starting eleven.

It was a terrible blow to their footballing morale. Mike was angry and Bernie was positively volcanic with rage ('When Bernie burned,' said Mike, 'it was not pleasant to behold'), and they decided there and then to walk out, shouting as they departed: 'You can stick your effing team up your arse!'

After licking their wounds for a while, and missing desperately the cut and thrust of the sporting competition, they set up their own celebrity club - 'The TV All Stars'. They then recruited a mixture of comedians and comic actors (such as Roy Castle, Alfie Bass, Johnny Hackett, Norman Rossington, Anthony Newley, Tom Courtenay, Jimmy Tarbuck, Bernard Bresslaw and Ronnie Corbett), although most hardened ex-pros found them too frivolous to favour. There would still be a certain amount of interaction between the old and new clubs, with a few players switching allegiances back and forth, but, increasingly, the 'roundheads versus cavaliers' distinction in their respective identities discouraged too much inter-club fraternisation ('It's fair to say most of the Showbiz team thought we were a joke,' Mike Winters later complained).

The TV All Stars, in deliberate contrast to the now rather dour Showbiz XI, offered an unapologetic combination of football and fun, with pre-rehearsed bits of comic business slotted into the sporting action. Usually captained by Bernie, their attitude was that 'we're comics who act that way on and off the field'.

Curiously enough, however, it was the TV All Stars, rather than the Showbiz XI, who proved the more politically engaged. In 1961, for example, when professional players, campaigning for the abolition of the maximum wage, were threatening to strike, the players' union planned some fundraising matches. While the Showbiz team declined to help on the grounds that they wanted to remain apolitical, the All-Stars happily obliged, winning a degree of gratitude within the sport that caused some resentment among their more cautious rivals.

There was actually a grudge match between the two teams in the early Sixties on a pitch near Croydon Airport. Notable enough to be filmed for television, the formidable-looking Showbiz XI team included Sean Connery and Des O'Connor as well as former England captain Billy Wright and former Wales captain Wally Barnes, while the rather less formidable-looking TV All Stars were heavily reliant on their one regular ex-pro, the former West Ham defender Malcolm Allison.

The bad blood was sloshing back and forth between the two teams even before the referee first raised his whistle. 'Our opponents were strutting around the pitch as if they had already won the match,' Mike Winters would moan, 'making condescending remarks about us'. Des O'Connor was overheard boasting that his team would aim to 'ease off' once they were seven goals ahead, causing the nearby Bernie Winters to bare his top two protruding teeth in angry indignation.

Once the game kicked off, it was obvious that any old friendships had now been firmly forgotten, as a flurry of feet, fists and elbows came flying in with abandon. 'It was brutal,' Mike Winters would recall.

Sean Connery kicked Ronnie Corbett high up into the air as if he was flicking away an unwanted Haribo. The terrier-like Corbett, once he had re-emerged from deep in a muddy puddle, managed to drag his studs down the back of Connery's ankle. Mike Winters then collided with the music executive Ziggy Jackson and broke one of the latter's legs ('It was an accident,' he protested). Those who were still on the pitch for the final few minutes would see playmaker Bernard Bresslaw lay the ball off to Malcolm Allison, who cut inside and struck a thirty-yard shot straight into the top corner of the Showbiz XI's goal, thus winning the game 1-0 for the TV All Stars. It was an unlikely victory that was celebrated long and hard.

Probably their proudest moment, however, would occur in 1966, the year of the Aberfan disaster, when the Winters brothers led a celebrity team out on to the Cardiff City pitch at Ninian Park to raise money in Wales' first-ever Sunday match to help the victims' families. The TV All Stars met a Welsh International XI before a crowd of 15,071 and battled their way to a 7-7 draw, raising more than £3,000 for the disaster fund.

Mike and Bernie, like burnt-out pre-Kloppian gegenpressers, would reluctantly hang up their boots in 1969 (an event commemorated by Bernie having a cartilage removed). The TV All Stars would play on for a while under new management, and the Showbiz XI would continue all the way through to today, but, looking back, it seemed like the end of an era for the comic footballing fraternity. Football, like cricket, was fading, and golf, of all games, was growing.

A harbinger of what was about to happen arrived late on in the 1960s, when David Frost welcomed Bob Hope on to his weekend TV show and, rather than quiz him in detail about his stand-up career or his many popular movies or his special comic gifts, elected to ask him to get up and demonstrate, at considerable length, his putting ability by knocking a succession of balls across a mat and into a training cup, and then move on to a similarly convoluted driving exercise. This must have seemed, for the vast majority of the watching audience, a most peculiar, and arguably quite unwelcome, kind of indulgence, but for Britain's budding comic golfers it probably seemed like a broadcasting seal of approval.

Why were so many comedians now drawn to golf? The traditional reason - which was, and to some extent still remains, very relevant - was that it was simply the most convenient leisure activity for entertainers who worked at night and had most of the day free. A round or two of golf enabled the resting comedian to wake up and emerge into the fresh air, get some moderate exercise in pleasant and semi-private surroundings, and socialise with one or a few of their co-stars in a relaxed and healthy context. The facilities were in easy access, whether one was working at home, or touring, or in summer season - there was always a local golf club from which one could inveigle an invitation - and the al fresco experience was an excellent contrast to the smoky, artificially-lit and adrenaline-driven thrill or ordeal of the variety theatre or recording studio.

It was also a far less dangerous game than football, cricket or rugby, which greatly reduced the risk of broken bones, pulled muscles or unsightly bruised skin, and it was an activity one could pursue well into middle age and beyond. To comedians, therefore, it seemed like a tailor-made form of relaxation.

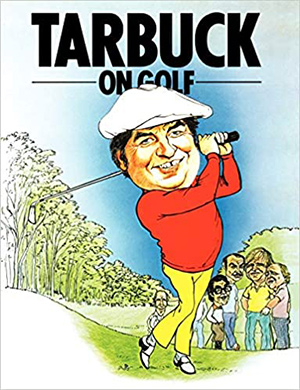

So powerful was golf's pull on the comics of the era that many of them, like iron filings to a magnet, were driven to live as close as they could to a decent golf club. Bruce Forsyth, for example, found a home practically next door to Wentworth, Jimmy Tarbuck based himself a putt or two from Coombe Hill and Ronnie Corbett (in a house called 'Fairways') settled a mere shank away from Addington. Even Eric Morecambe, for whom the game never held that much interest, found himself living next door to a golf club at Harpenden.

It was not long before many of these comedians, having bedecked themselves with abandon in the garish outfits so beloved by the guardians of the game, were not only playing regularly and obsessively but also (in the case of Bruce Forsyth, Jimmy Tarbuck and others) presiding over their very own pro-am tournaments. They had become, to Britain's unconverted masses, bona fide golf bores, droning on about the subject with what seemed like far more enthusiasm than they showed when discussing comedy.

There was nothing intrinsically wrong about this. One person's all-absorbing hobby is another person's painful headache, but, so long as one respects the other's right to be left alone to pursue their own passion, there is no reason for any resentment. The problem was that the golf-mad comedians could not keep their obsession to themselves. They seemed determined to share it with everyone else.

The fact that, for what felt like a very long period of time, they did so was not their fault. It was the fault of television management.

Many entertainers can delude themselves into believing that what audiences really want from them is not their primary skill but one of their secondary interests, which is why some musicians attempt to make movies, some talent show judges bid to burst into song and some actors convince themselves that they are actually political theorists. They have every right to do so, in their spare time, but it is down to management to stop them from inflicting such self-serving fallacies on the audience.

This, from the Seventies through to the Nineties, is what television management signally failed to do when it came to the sport of golf. The broadcasters, for some unknown reason, seemed content to indulge comedy's golfing fraternity as it did its best to make everyone else feel that they were fellow members of a virtual clubhouse.

This was the big difference compared to the racing and the cricket and the football. Those interests were kept off duty and off the screen; if you wanted to go to see them, you could do so, but the TV comedy was kept hobby free. Golf, however, was allowed to seep deep into the screen.

Out went the dinner jackets and the velvet bowties. In came the garishly-coloured diamond-patterned sweaters and the tartan trousers. Out went the stories set in family homes, factories, pubs and offices. In came the tales about what happened on the fairway, the rough and the bunker.

Everybody seemed to be at it: Corbett, Forsyth, Tarbuck, Eric Sykes, Harry Secombe, Norman Wisdom, Kenny Lynch, Cannon & Ball, Hale & Pace, Tom O'Connor, Tim Brooke-Taylor, Jim Davidson, Stan Boardman, Bobby Davro, Mike Reid, Bernard Manning, Frank Carson, Charlie Williams, Russ Abbot, Jasper Carrott, Eddie Large, Les Dawson - the list went on, and on, and on.

They ensured, as if to demonstrate golf's sudden hegemonic hold over British humour, that their favourite game was just about everywhere on television, popping up, for example, in an episode of Sykes (which featured British Open winner Tony Jacklin), discussed in Dave Allen At Large, featured in a sketch on The Dick Emery Show, used as the basis of a round in The Generation Game, adapted to involve Hitler in The Freddie Starr Experience, dominating an edition of Terry & June, and figuring in several stories in The Two Ronnies (including the all-too apt monologue, 'All you ever think about is bloody golf!').

Then came the books: Ronnie Corbett's Armchair Golf; Tarbuck on Golf; Bruce Forsyth's Golf ...Is It Only a Game? and Tim Brooke-Taylor's Golf Bag. The permanently Pringled Tom O'Connor churned out a veritable library on the subject, including such volumes as From the Wood to the Tees, One Flew Over the Clubhouse and Golf...Is Where You Find It.

Then came the videos: Bruce Forsyth's Good Game, Good Game!, Jimmy Tarbuck's Nightmare Holes of Golf (volumes 1 and 2), Mike Reid's Under Par (volumes 1 and 2), Eric Sykes' How To Cheat At Golf, and - yes, him again - Tom O'Connor's The Funny Side of Golf. Even Peter Cook, during one of his idle moments, was somehow compelled to release one: Peter Cook Talks Golf Balls.

There were also CDs - such as Frank Carson's Famous Golf Stories - and records - such as the double B-sided single Follow The Fairway/Lee Trevino, released by EMI in 1976 and credited to 'The Caddies,' a super group of golf bores that consisted of Henry Cooper, Tony Dalli, Bruce Forsyth, Kenny Lynch, Glen Mason, Ed 'Stewpot' Stewart and Jimmy Tarbuck.

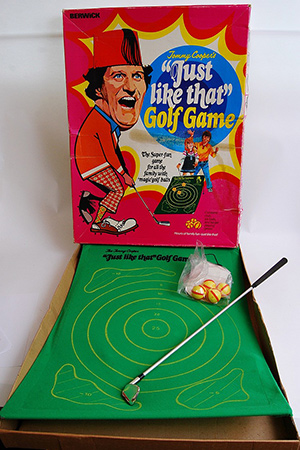

There was even a game: Tommy Cooper's Just Like That - a 'super fun' activity that involved a small golf club, a green mat, six plastic balls and some Velcro.

As if all of this over-exposure was not enough, the comedians were further indulged by the talk show hosts: both Michael Parkinson and Terry Wogan were themselves avid golfing fans, and were thus only too happy to sit back and listen to all of the same old stories all over again. There was also a series hosted by Peter Alliss, the golfer-turned-commentator, called Around with Alliss, in which several visibly delighted comedians were given the opportunity to talk about golf whilst playing golf - all, supposedly, for the nation's entertainment.

To any young person pondering this strange phenomenon today ('What did you do during the golf bore war, Grandad?'), the assumption might be that all of this was merely a case of supply in response to demand, but that is not how things actually were. There was barely any demand outside of the comedy (and possibly the golfing) community; there was simply far too much unsolicited supply.

Absolutely no one, for example, appeared to be yearning for a golf-based sitcom, but that is what everyone was offered in 1989 when Eric Sykes (nine years on from his own golf-themed silent movie Rhubarb Rhubarb) popped up in ITV's Johnny Speight-scripted sitcom called The Nineteenth Hole. Portraying the permanently harassed secretary of the very conservative Prince's Hill Golf Club, located on a private estate, Sykes was not required to do much while various other characters complained, in a painfully sign-posted way, about matters relating to class, gender, ethnicity or golf. The ratings were poor, and the reviews were poorer: 'Eric Sykes should have had nothing to do with this sorry sitcom,' wrote one critic, while others plucked the predictable puns to dismiss it as 'not up to scratch,' 'well below par' and 'not so much an eagle as a turkey'.

It was at this point - or really some time long before it - that a producer should have taken some of these comedians to one side and said, 'I'm sorry, luvvie, but it's over: the public just aren't interested,' but it seems that no one did. The delusion, therefore, continued to be indulged.

The nadir, or zenith - depending on one's perspective - of British comedy's extraordinary golf bore-a-thon arrived in 1996 when, astonishingly, someone at the BBC was persuaded to commission a Jimmy Tarbuck golf-themed virtual reality game show entitled Full Swing. This was a programme of rare and surreal madness, as if Brando's Colonel Kurtz from Apocalypse Now had been left to run amok in a studio after binge-watching Bullseye and Grandstand.

The format, for one thing, was so fussily over-elaborate that there was a risk of viewers passing out from tedium-triggered enervation while it was still being explained. Round One ('Three For The Tee') featured a trio of plucky contestants paired with celebrity golfers (or, more accurately, celebrities who golfed a bit), with the level of complexity for each set questions determined by how well each player fared swinging on the golf simulator; each correct answer advanced the contestant towards the virtual pin, and the top two pairs survived for the next stage.

Round Two ('Fairway or Foul') saw the remaining couple of contestants answer questions to enable their playing partner to hit the ball towards the simulated green whilst trying to avoid such virtual hazards as bunkers, rivers and waterfalls, along with, of course, rabbits digging holes.

Round Three ('The Final Green') had the last surviving contestant answering up to four questions correctly to win sufficient time for their celebrity partner to putt as many as ten golf balls into the hole and win them the star prize of a slightly exotic holiday.

The show began each week with a very pleased-looking Tarbuck, dressed predictably enough in fairway-friendly sweater and slacks, driving on to the studio set in a large white golf buggy. After telling a couple of run-of-the-mill gags from a seated position, he would leap out of the vehicle and trot across the grass (which, he appeared immensely proud to announce, 'is real grass that has to be watered and mowed') to tell a few more run of the mill gags and then meet the dazed-faced contestants.

He then introduced the contestants to their celebrity golf-playing partners, who, each week, turned out to be such characters as Tarby's great mate and former Goodie Tim Brooke-Taylor, Tarby's other great mate ex-Liverpool centre forward Ian St John, another one of Tarby's great mates Frank Carson, yet another one of Tarby's great mates Kenny Lynch, and, of course, Tarby's great, great, great mate Ronnie Corbett. It somehow felt as though the whole show was aimed purely at Tarby's other great golfing mates at home, who were probably sitting there, in their houses next to their local golf clubs, watching contentedly whilst polishing their assortment of vintage niblicks.

Due, however, to nationwide indifference, as well as critical contempt (one reviewer, who denounced the programme as 'putter nonsense,' proposed the alternative title of Spot the Prat in the Pringle), the BBC - as if awaking from a trance - promptly cancelled the show after a mere eight episodes, and even passed on the chance to show the already-filmed Christmas special. Jimmy Tarbuck was left incandescent with rage, having convinced himself that a second series would have changed millions of opinions, and he would sulk about supposed BBC 'sabotage' for many years after.

The cancellation, however, sounded the clanging death knell for three decades of quite bizarre sporting self-indulgence. A new generation of comics - most of whom had never seen the inside of a Pringle sweater, let alone laid eyes on a pair of plus fours - were let loose in the schedules, performing comedy about things that immediately engaged their audience, and the old guard now found that they suddenly had more time than ever to play golf.

That was their salutary lesson. What, however, can the rest of us learn from this odd sporting saga?

Surely the main lesson is that entertainers, and producers, should never lose sight of the fact that they are there to serve the public, rather than themselves. They are there to be part of the broader community, and to listen, observe, reflect and engage with it - not merely impose whatever amuses their own little clique upon the broader watching public.

That distinction, between what entertains the performers and what entertains their audience, ought to be easier than ever before to respect and maintain. Comedians these days can sublimate and satisfy their own non-comic interests via a variety of more selective and subscription-based outlets, such as the burgeoning industry that is podcasts. Producers, thanks to their access these days to plenty of audience feedback, ought to be well-placed to protect performers from any tendency towards self-indulgence. They might even, in moments of weakness, keep in mind a little mantra: 'Think golf. Think Full Swing. Think NO'.

TV comedy should be a mirror for us, not the performers. It should make us laugh because we see ourselves in it, not because we see them. The better both parties realise this, the better it will be for all.

That's how worthwhile relationships between performers and audiences are cultivated. That's how real loyalties blossom. That's how humour is genuinely shared. We should leave them to enjoy their leisure; they should leave us to enjoy their work.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more