Stranger Things: When sitcoms strain to be different

There are two rules of thumb for writing an effective sitcom. One is 'write about what you know', because you need to believe in it, and the other one is 'write about it in a way that makes others recognise it', because you need your audience to believe in it, too. Rules, however, can be broken, and it is always interesting to see what happens when they are.

In the case of British sitcoms, there are three unusually notable examples from the genre that provide some sobering insights into what can happen when the creators decide not to write about what they know, and not to write about it in a way that makes others recognise it. One is Jimmy Perry's The Gnomes Of Dulwich (1969), the second is David Croft and Jeremy Lloyd's Come Back Mrs. Noah (1977) and the third is Eddie Izzard and Nick Whitby's Cows (1997).

The Gnomes Of Dulwich was an intriguing venture by Jimmy Perry. Having just scored a success (alongside David Croft) with Dad's Army, which was based on what he knew (he had himself served in the Home Guard), he proceeded to write another sitcom that, at least at first glance, was based on barely anything from his own experiences.

It was not envisaged initially as a sitcom at all. It was conceived originally simply as a short self-contained sketch, possibly for Morecambe and Wise.

Perry thought it would be fresh and funny if he used the unfamiliar situation of a couple of British garden gnomes, being alarmed by the arrival of a pair of plastic versions imported from Hong Kong, as a satirical take about the current state of race relations. 'I don't know what Britain is coming to,' mutters one of the old gnomes. 'They should stop letting in these foreign gnomes. I mean, would you let your daughter marry a plastic gnome?'

It was hardly a deep piece of political commentary, but it came as a welcome contrast to some of the xenophobic prattling that seemed to be polluting the rest of the mainstream comic output of the time, and, in the context of a short and snappy sketch, it made its basic point rather well.

The problem was that when Michael Mills, the BBC's then-Head of Comedy, read the script, he liked it so much that he told Perry to develop it into a six-episode sitcom for BBC2. The reason why this was a problem is that Perry had not really thought that hard about the concept - it had merely been one of those brief conceits for a one-off comic routine, to make and then move on. Now that he unexpectedly had a new commission on his hands, he needed - very quickly - to work out how, and why, it could work when opened out and spread across a whole series.

Perry never really seemed to do so - at least not in a consistent and fully coherent way. Collect his promotional interviews together today and they form a confusing mixture of anthropomorphic curiosity, allegorical ambition and Brechtian Verfremdungseffekt.

Sometimes he would claim, in spite of the fact that he had lived for years in a fourth-floor flat without so much as a window box, that he had mainly been inspired by a long-standing and genuine fascination with traditional garden gnomes. 'They are wonderful little people,' he told The Stage newspaper at the time. 'I've never been able to walk past a garden without wondering just what he's thinking.'

Sometimes he would claim that it was purely a way to make people question whatever they took for granted. 'The basic idea,' he said, 'is to simply look at the world of human behaviour on a different level - from the eye level of a gnome.'

One thing he was clear about was that it was a major gamble on his part. 'I'm taking a big chance,' he admitted. 'If the idea doesn't come off, people will think I'm some kind of nut.'

The Gnomes Of Dulwich - the title was an allusion to the 'Gnomes of Zürich' (a phrase, much-used by Labour Party politicians of the time, referring to the secretive practices of Swiss bankers), featured the duo of Terry Scott and Hugh Lloyd (well-known for their previous popular sitcom, Hugh And I) along with John Clive. Scott played a gnome called Big, Lloyd was one called 'Small' and Clive appeared as one known as Old. Other characters included the cheap foreign pidgin English-speaking newcomers who lived next door: Plastic (Leon Thau) and a couple of 'dishy' young women called Dolly (Anne de Vigier) and Rita (Lynn Dalby). Also appearing was John Laurie as the Pope-like Top Gnome.

Each week the foot-high stone gnomes would sit by the pond in their garden and discuss various issues relating to such subjects as immigration, religion, public schools and war. Humans would only be glimpsed briefly via a shot of a giant foot or hand. The gnomes ended up, by the final episode of the series, taking residence, via a jumble sale, in the garden at 10 Downing Street.

It was a brave and imaginative idea (indeed, it can, to some extent, be seen as anticipating later 'humans viewed through a stranger's eyes' satires, from Mork & Mindy - 1978-1982 - and 3rd Rock From The Sun - 1996-2001 - right through to Syfy's 2021 series Resident Alien), but it never managed to be more than a noble failure. For one thing, the sitcom was dogged by technical problems right from the start. Being broadcast in colour on BBC2, it was important for the actors to seem as life-like as possible as gnomes, and this meant very elaborate costumes and unusually detailed make-up as well as trick photography.

This caused unrest amongst the cast and crew alike. The actors quickly grew to hate being gnomes - partly because it took ninety minutes to a couple of hours each time to get them into their outfits and paint on their make-up, partly because it was then hugely uncomfortable as they rapidly heated up under the studio lights, and partly because they felt that they were barely recognisable as performers - and the crew felt frustrated by the numerous imperfections that remained as they 'shrank' the gnomes whilst introducing the odd 'giant' human prop. Terry Scott, in particular, being an actor notorious for his earth-shaking eruptions of bad temper, was soon emptying sets with his red-faced rants about how 'intolerable' it all was ('People wanted to shoot me after that sitcom,' the actor would later say bitterly. 'I wanted to shoot myself!').

The sitcom also struggled because Jimmy Perry simply wasn't suited to such wide-ranging social and political satire. Here was a writer whose own past was, more than for most, his muse (inspiring not only Dad's Army, but also It Ain't Half Hot Mum - which was based on his wartime experiences in India - and Hi-De-Hi! - which drew on his days as a Butlins Redcoat), seemingly starving himself of what rooted his work to reality.

Not even he appeared convinced that he had what it took to be a sharp social commentator ('I must admit,' he later told me, 'I read far more newspapers than usual!'). Each episode, as a consequence, seemed to bounce around setting up random old-fashioned sitcom gags (including the painful exchange: 'What are you doing in there?' 'Minding my gnome business') as if to distract the viewer from the thinness of each ostensibly 'weighty' theme.

Although Perry himself would always defend the show ('It was my own personal thing - a bit kinky perhaps - but I loved it') and claim that it won enough praise to qualify as a cult success, the majority of the reviews at the time, in truth, were fairly brutal. A critic for The Daily Mirror, for example, branded it a 'maniac conception' and an 'hysterical idea', before adding: 'I watched last night's curtain-raiser with the growing disbelief that such a monstrosity could be allowed to grovel on to our screens'. Several similarly damning judgements would follow as the weeks went on.

It was much the same when, a few months later, the show was given a second airing on BBC1. 'I found the script banal [and] beyond rescue,' wrote one reviewer. Another simply said: 'What a load of rubbish'.

The Gnomes Of Dulwich was a sitcom that required an absolute clarity of vision and purpose to make it work, but, alas, it never received it. Neither the script seemed sure of what it was trying to say, nor the audience of what it was trying to mean. The result was a colourful, quaint, confusing and, for some, rather creepy-looking mess.

Ironically enough, Jimmy Perry's usual writing partner, David Croft, would suffer a similar fate almost a decade later when he and Jeremy Lloyd co-created Come Back Mrs. Noah. This comparably bizarre sitcom was devised as a vehicle for Mollie Sugden, but rather than placing her in a familiar domestic or work-based situation, Croft and Lloyd elected to send her off into space.

Inspired solely by the burgeoning cultural and commercial impact of Star Wars, which had recently been released, Croft and Lloyd somehow managed to convince themselves, even though neither had much interest in (let alone experience of) science fiction as a genre, that the time was right for a sci-fi sitcom. They also, more plausibly, managed to convince themselves that no performer would seem as comically incongruous in such a context as the woman currently best-known for playing the pompous pussy-lover Mrs. Slocombe in their own successful sitcom Are You Being Served?.

Working incredibly quickly, they thus came up with the pilot script for Come Back Mrs. Noah. Set in Pontefract in 2050, at the site of the UK's space exploration complex, the winner of Modern Housewife Magazine's cookery competition arrives for her prize: a visit to the spaceship that is docked there. Once she is inside, however, it spontaneously clicks into action and shoots off into orbit, leaving her and the skeleton crew stranded in space.

One might have thought, once this premise was presented, that an executive might, to echo David Croft's past character of Sgt Wilson, have pondered both the potential 'legs' of the project as well as the likely budget and asked, 'Do you think that's wise?'. In fact, at the time, Croft's undeniably impressive track record, combined with the BBC's then-admirable trust in its talents, meant that even an idea as odd as this sailed through the vetting process without even a quibble.

'It speaks volumes about the flexibility of the BBC at that time,' Croft would confirm to me, 'but we rushed it along without any opposition at all. One of my concerns, when I spoke to [Head of Comedy] Jimmy Gilbert, was that everyone would soon be trying to do something similar in this area, because "space" was suddenly all the rage, so I was greatly bothered about the danger of duplication. So I told him that Jeremy and I had an idea that we really liked, and that we wanted to do a pilot, but that the idea was so "hot" that I'd prefer not to tell him what it was about. And Jimmy, to his eternal credit, didn't ask for a script, he didn't question it at all, he just told me to go ahead and do it.'

Croft, as the show's producer as well as co-writer, was thus, effectively, in more or less full control of what followed. He signed up Sugden for her first sitcom starring role, along with many other members of his unofficial repertory company of comic actors, including Ian Lavender (as a roving reporter called Cunliffe), Donald Hewlett and Michael Knowles (as a pair of physicists called Carstairs and Fanshaw) and went ahead with the recording session.

Making do with low-budget 'space age' sets that looked like they had been made from pieces of cardboard spray-painted battleship grey, and the kind of hastily-assembled mechanical props that normally popped up with Arthur English in episodes of Are You Being Served?, it was a rushed production that hardly suggested a series would be a logical progression. Sure enough, when it was broadcast at the end of 1977, the critics slammed it as a waste of time, with one dismissing it as 'a humourless assembly of actors from various other television series struggling with a script which contained only one decent joke in half-an-hour', and another complaining: 'Everything is spelt out, no joke is left unrepeated and the co-writer and producer David Croft really ought to have known better than to try to pass off this rubbish'.

According to Croft, however, the reaction inside the BBC was uniformly positive. 'Everyone liked the pilot,' he claimed, 'so Jimmy Gilbert told us to go ahead with the first series.'

This was surely the moment when Croft and Lloyd should have paused to reflect on the pilot - which had ended with Mrs. Noah stuck helplessly in space ('I've left a chicken in the oven!') and posed themselves the question: 'And now what?' Instead, it seemed, they simply pushed ahead on instinct, writing episode after episode without any clear sense of where they wanted to go, let alone where they expected audiences would want to follow them.

Someone tries to battle the absence of gravity in order to make scrambled eggs; someone else tries to battle the absence of gravity to go to the lavatory; someone flirts with someone else; someone rebuffs someone else; someone has a tea party; someone has to unblock the sink; and there are numerous arguments. That is, more or less, how the series rambled on. It was like any other sitcom, except it was set in space, and had strange sets, and far too much sub-standard dialogue:

GARSTANG: We're still in the news, Mrs. Noah.

MRS. NOAH: Oh, I can't be bothered with that. I'm having trouble with me 21st Century crystal-controlled atomic non-stick pan!

GARSTANG: What's the matter with it?

MRS. NOAH: It's so heavy. I can't toss me pancakes.

CUNLIFFE: You make the batter too thick.

MRS. NOAH: I do no such thing!

CUNLIFFE: Look at those Yorkshires you did yesterday: I put mine down the rubbish chute and they did twenty-five orbits! They'd still be going round if the Russians hadn't brought them down with a death ray! That nuclear missile made no effect at all, did it? Hey, it's a good job you didn't make your fruit cake - we would've started World War Three!

MRS. NOAH: That's it - I am not cooking for you anymore!

One of the oddest things about Come Back Mrs. Noah is how little Mrs. Noah has to do or say. As starring vehicles go, Mollie Sugden would have been forgiven for feeling short-changed. In a remarkable number of scenes, Hewlett and Knowles drive the action on, while she is not much more than a prompt, asking such questions as 'What will we do now?' 'What did he say?' or 'And what do you suggest?'

It was never clear what Croft and Lloyd were seeking to achieve, other than to use an utterly unbelievable backdrop for some predictable and laboured visual gags. That was the principal problem: why was the audience supposed to believe in, and care about, any of this?

There was, initially, a visual novelty value about cups of water flying across the set, and some primitive trick photography, but, after that had worn off, it was easier to focus on the fact that there was nothing that made much sense. Visitors would keep popping up to the space vessel from mission control on Earth, as if they were on a day trip from Leeds, and then fly off again, while everyone on board continued to be told that they were stuck in their claustrophobia-inducing ship; the physicists would alternate wildly between an urgent concern about their situation and a whimsical interest in various strange experiments; while Mrs. Noah often stood about looking slightly bemused.

Croft and Lloyd had written themselves into a corner: if they resolved the storyline and sent Mrs. Noah home, they would cut their own sitcom short, but if they ignored the logic of the storyline they would literally have nowhere to go. It was already clear, midway through the six episode series, that they were running out of ideas as to how to maintain a sense of momentum without having to rely on the same old conversations with mission control, and, by the end, the sense of exhaustion was evident in every laboured scene.

The key reviews were perhaps most noticeable by their absence. The show was, in general, shunned. The odd criticism would come through - such as the review that complained that the sitcom's premise was 'just about as contrived as you can get', and that the whole series amounted to 'the biggest heap of déjà vu for yoinks' - but most journalists simply ignored the show from start to finish.

David Croft, like Jimmy Perry before him, would remain defiantly proud of his short-lived venture, insisting, many years later, that it had been an artistic success. 'Jeremy and I still think of it as one of the funniest things we have ever done,' he told me, 'but, sadly, it just didn't do well enough in terms of audience figures for it to go on.' He laid most of the blame for this failure on to Kenny Everett, against whose very popular ITV show the sitcom was scheduled, and stubbornly refused to acknowledge that there might, just possibly, have been a problem with the premise.

'The show was never repeated,' he wrote in his autobiography, with a sense of incredulity. 'At home I still watch it from time to time, when in need of a good laugh tonic.'

As if 'Mollie Sugden lost in space' had not done enough to discourage commissioning editors from taking wild gambles with the sitcom format, Channel 4 proved even more reckless almost two decades later when it decided to commission a sitcom about cows.

The idea for this sitcom came from the up-and-coming stand-up comic Eddie Izzard. He (Izzard identified as 'he/him' at that time) had exhibited some comic interest in cows for quite a while, having discussed various things relating to them and their condition during his stage routines, but, even so, it was still a considerable surprise when he decided that his first venture into sitcoms would be completely bovine in nature.

It was less of a surprise that it took him so long to actually get it made. He first mentioned the project in 1993, when he told a journalist: 'I'm going to make a TV sitcom called The Cows [sic]. It hasn't been cast yet, but I want to use people from the comedy circuit in London.'

Things then went quiet for three years, until, early in 1996, it was announced that he and Nick Whitby (whose previous writing credits included several episodes of Boon and the Sean Hughes vehicle Sean's Show) had completed a pilot script that had been picked up by Pozzitive Television with a view to make it for Channel 4. The promise was that it would 'revolutionise the tired TV sitcom format'.

Izzard himself, however, seemed to contradict that claim when he came to promote the show, explaining, in his slightly woozy way, that, as 'a telly addict', his ambition was to make the 'totally normal sitcom I have always wanted to see': 'I realise that it's all a bit, um, cowy for some people, but after the second showing I hope they stop seeing cows as such, and get the jokes, the plotlines and the characters. I want [viewers] to like them as people.' This did cause a few observers to wonder why, if that was his hope, he hadn't just made the show considerably less 'cowy' and written it about people instead, but by this time Izzard was very much the flavour of the month in industry circles and no one seemed inclined to question his judgement.

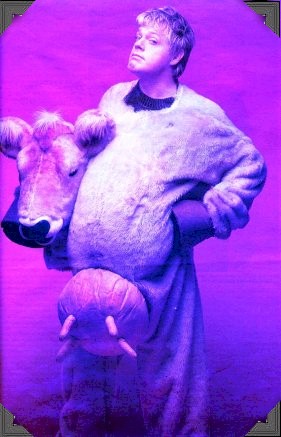

There were, however, predictable problems when the pilot episode came to be recorded, and, as had happened with The Gnomes Of Dulwich, most of them revolved around the conceit of having actors hidden away inside costumes. The performers - who included Pam Ferris, James Fleet, Jonathan Cake and Kevin Eldon - were obliged to start putting on their outfits (which were originally made mainly of foam and latex) at six in the morning, and then stay in them until the end of the day, having to drink through straws while assistants held fans over them.

It took the first attempt at filming the show, however, for the team to realise that there was a serious design issue to be overcome. 'The first recording was a disaster', Izzard would recall. 'The lights were melting the latex, and we had this vision of the actors suffocating underneath it all. We feared they might just disappear into a heap of hot black rubber.'

They overcame this by slightly adjusting the costumes and reducing the temperature on set, and the second recording session was far more successful. It was only after it had been completed, however, that they realised that the hidden head mics that had been used had not been as effective as expected, and so, rather than try for a third time, it was decided that the actors would have to redub many of their lines instead.

The hour-long pilot finally reached the screen on New Year's Day, 1997. It was described in previews as being 'about the Johnson family - a family who enjoy and suffer most of the usual ups and downs and are no less ordinary for being cows'.

The plot, such as it was, concerned the imminent wedding of Rex, an irritating, pot-smoking, yuppie-style bull, to Pinky, a meek human woman who appears simultaneously completely unfazed by being with cows whilst puzzled by just about everything that they say and do. After overcoming their aversion to such an inter-species union, the cows head off (in their cow-mobile - a specially-painted black and white Citroën) to see their great aunt Grace, a bovine Lady Bracknell type, in the hope of persuading her to pay for the wedding. Grace agrees, but, as she herself predicts, is promptly killed after being struck by lightning. The cows inherit the stately home and host the wedding, but, once married, Pinky runs off screaming after witnessing Rex licking his nostrils. Thor then decides to enter politics, but wrecks his chances after a disastrous conference speech. Back at the stately home, they gather to hear Grace's will via a séance, but it is challenged by the now-pregnant Pinky and her parents, and the cows agree to exchange homes with the humans.

Watching it was (and still is) an extraordinary experience, somewhat akin to trying to follow Marlon Brando mumbling his way through one of his lesser movies, while being drip-fed Châteauneuf-du-Pape with your head stuck in a space helmet. None of the characters were likeable, none of the action was believable, and some of the dialogue, when it could be heard above all of intrusive and decidedly forced-sounding audience laughter, seemed aimed at people in various states and degrees of intoxication:

SHIRLEY: Pinky?

PINKY: Um, yeah?

SHIRLEY: Do you wear a girdle?

PINKY: No, I don't.

SHIRLEY: Stays?

PINKY: No.

SHIRLEY: Hoists?

PINKY: No.

SHIRLEY: What underwear do you wear, then?

PINKY: Don't you think this is a bit personal?

BOO: I think it's a fair question.

PINKY: All right...I wear...knickers.

SHIRLEY: Knickers? Holy God! How much do they weigh?

Izzard had described the Johnsons as 'just another crap family like the rest of us', but that was about as helpful as describing the Borgias as 'just another crap family like the rest of us'. If the cows were meant to symbolise difference in society, and the need to respect and embrace it, the combination of the implausible situations, distracting costumes and unappealing personalities certainly undermined the effectiveness of the message, and if the cows were merely intended as an unfamiliar way to examine a familiar family unit, then the writers would surely have been better advised to come up with fresher characters instead of consigning stale ones to multiple layers of latex.

The reaction to the broadcast at the time was, unsurprisingly, extremely negative in nature. Many critics noted the family resemblance to Gary Larson's The Far Side comic strip (which featured talking cows on a regular basis), as well as the clumsiness of trying to translate that for a medium such as television.

One reviewer, with regret, judged the pilot 'one of the great disappointments of the New Year television schedules', as it had 'failed to be funny in the most embarrassing way'; another complained that the sitcom 'simply didn't work once the novelty of a family of cows had been milked'; and a third spoke for many when they focussed on the technical naïveté of the basic enterprise: 'Unfortunately comedy comes about with the help of facial expression, as well as words, and in this excuse for comedy (because of the fixed masks) the actors' words were all muffled and the faces were made expressionless. The whole experiment was a disaster.'

Apparently, Izzard and Whitby were already mid-way through writing scripts for a series when Channel 4 informed them that it would not be going forward, but it surely could not have been much of a surprise. Whatever was still making sense to them was not making sense to anyone else.

It would later be alleged that Izzard's agent viewed the debacle as a salutary learning experience for him, 'getting sitcoms out of his system' and making him focus on his stand-up career. That was probably right. The project might have fared better if it had been designed, and funded, as a Simpsons-style animation, but, even then, it would have needed - like The Gnomes Of Dulwich and Come Back Mrs. Noah before it - far more thought, discipline and attention to its intended audience to have made it an ongoing sitcom concern.

None of this is meant to serve as any kind of rebuke to those who seek to break the rules. The last thing we should be doing now is discouraging sitcom writers, and commissioning editors, from being imaginative, innovative and brave.

What we do need to do, however, is to encourage the taking of far more time and effort into the preparation of each experiment. Be different, be daring, but never lose sight of why you're being different and daring. The end of the process should always be the engagement with an audience, rather than just the indulgence of a personal dream.

The Gnomes Of Dulwich, Come Back Mrs. Noah and Cows did not fail because they broke the rules. They just didn't break the rules well enough.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more