Random acts of kindness: Comedians being good to each other

There is a nice and rather touching anecdote that Paul McCartney tells of his time with John Lennon. They were having an argument, as bandmates often do, when Lennon suddenly noticed that one of his cutting remarks had gone in deep and drawn some blood, so he paused, pulled his glasses down his nose and said, 'It's only me, Paul' - then he pushed his glasses back up and carried on with his argument.

Comedians can be like that. Striking blows is so instinctive that sometimes they forget their own strength.

Most of them, however, are nothing like as heartless as they can seem when the normal filters are suspended and they are just trying to be funny. The all-consuming concentration required to come up with things that will make other people laugh can make even the kindest of people seem carelessly cruel.

Some comedians, it is true, actively encourage the myth that they come from a rare and special breed that feeds on nothing but the misfortunes of others. Groucho Marx, for example, once famously said: 'An amateur thinks it's really funny if you dress a man up as an old lady, put him in a wheelchair, and give the wheelchair a push that sends it spinning down a slope towards a stone wall. For a pro, it's got to be a real old lady.'

It is also the case that some comics, hardened by hecklers and soured by the spirit of competition, will be inclined to agree with the words of Gore Vidal: 'Whenever a friend succeeds, a little something in me dies'.

The good egg to rotten egg ratio in the comedy world, however, is actually about the same as it is in most other professional and personal contexts, and it is well worth remembering that there have been, and still are, plenty of comedians who, once the mic has dropped and the stage departed, are admirably kind, considerate, caring and decent people. Indeed, there are many instances of comics who, without attracting the attention of the tabloids (whose interest would probably not be piqued by such pleasantness anyway), have shown that their eagerness to help other people is as keen as their need to amuse them.

Take the case of Ernie Wise. As with all straight men in a double act, his on-screen job was usually to seem serious, impatient, irritated or even angry as a means of setting up and accentuating his partner's laughs, and this could make some observers speculate that, off-screen, he might be similarly sombre, stuffy and self-obsessed. In reality, however, he was generally a sunny-natured and kind-hearted man who, behind the scenes, was fiercely loyal, fair-minded and considerate.

When, for example, Eric Morecambe suffered a massive heart attack in 1968, and his chances of recovering sufficiently to resume his performing career would remain in some doubt for quite a while ('Nobody was really sure,' his wife, Joan, later revealed to me, 'that he would ever work again'), some partners' minds might have begun (however reluctantly) to ponder the possibility of a solo career, but not in the case of Ernie Wise. Eric was his partner but also, even more importantly, Eric was his friend, and there was never any doubt as to how devoted he actually was.

While Morecambe convalesced, Wise worked tirelessly to keep their double act in the public consciousness. He visited promoters, publishers, schools, luncheon clubs and fêtes, gave countless radio and newspaper interviews (never referring to himself as anything other than one half of a double act), supervised the publication of The Morecambe & Wise Joke Book and promoted the first repeat on BBC1 of their most recent TV series.

Throughout this period, Wise was courted by numerous producers and channels who wanted to use him as a solo performer, but he refused to even consider their often very lucrative proposals. Some influential figures, convinced that Eric was unlikely to come back on a full time basis, tried to get Ernie to let them start discreetly planning a future career for him on his own, but again he shunned all such suggestions.

The only engagements he accepted were those that presented him as representing 'Morecambe & Wise', and he also took great care to ensure that half of whatever he earned, no matter how great or small the sum, was sent directly to his partner. 'It was quite touching to see him do all of this,' John Ammonds, their regular producer at the BBC, would tell me. 'There were all kinds of rumours circulating, obviously, but he was absolutely devoted to Eric. He's a very nice man, Ernie, and I know what he did meant an awful lot to Eric.'

The kindness of Wise was not merely reserved for Morecambe. Without wishing to arouse any interest in the media, he kept an eye on the more vulnerable of his fellow performers and was quick to step in with support whenever he sensed that they were struggling.

As he once put it himself, he was 'always a great jollier-up of comics who are going through bad patches'. He said it was simply because 'I've been through it myself, so I know', but there was more to it than that. He genuinely cared about his fellow professionals, and, as a straight man, he knew what made comics tick not only on the stage but also off it.

Frankie Howerd was one of those comedians who benefitted, repeatedly, from Wise's considerate nature. They had first met in the late Fifties, when Morecambe & Wise were fighting their way back from the fall they had suffered after their disastrous debut TV series, Running Wild, and Howerd was sliding down into one of his own dark spells in the doldrums.

'We were at a charity function,' Wise would recall, 'and I remember on that first meeting commiserating with him, trying to cheer him up. Frankie had a much tougher time than we did. We had one another for support. He really had no one, even though his friends stood by him and did all they could. But it's tough when you're a single act and the phone doesn't ring.'

Howerd was inclined, in such bleak times, to curl up and hide away, but Wise, though never forceful, refused to let him be alone. He called him, wrote to him, visited him, and seized on any opportunity to give him an appreciative mention in public. 'It was all very humbling and touching,' Howerd would say, 'and it helped, it really did.'

Wise and his wife Doreen also went out of their way to invite Howerd to join them for dinner, accompany them to various show business events and even, on occasion, on holiday. It did not matter that Ernie, like Eric, was facing plenty of stresses and strains of his own as Morecambe & Wise continued to try to establish themselves on television; he always found time for the more senior star who was currently down on his luck.

A few years later, in the mid-Seventies, when Morecambe & Wise were by far the biggest act around and Howerd was again experiencing a depressing slump in his career, Ernie and Doreen used to socialise him with him in Malta, where both of them had holiday homes. The older comedian, depressed and frustrated, alienated a few of his friends at that time with his embittered rages at the perceived injustice of it all, but Ernie, knowing what he was going through, simply absorbed it and understood it.

'He had a very sharp tongue,' Wise said of these dark moods. 'Usually it was heavy sarcasm. He could be very prickly. Luckily he was a Morecambe & Wise fan, and we never fell out!'

Once they were back in Britain, Wise would take Howerd to the White City dog track whenever his own greyhound - 'Short Fat Hairy Legs' - was running. They never won anything (the aptly-named dog was somewhat on the slow side), but Wise would spend the evening talking Howerd through the various options that he was pondering and building up his confidence to battle his way back to the top.

'However great your success,' Wise would say, 'you never get rid of the taste of failure. You wear the scars for ever.' The consequence was that, however strong and bright his own career currently was burning, he always noticed when other ones were beginning to flicker and dim, and he did whatever he could to help them through to a better time.

Another comic with a similarly caring mentality was Wise's contemporary, Bob Monkhouse. Always quietly and discreetly, he helped innumerable performers and writers to either save their careers or rise to another level.

One former radio broadcaster, for example, was astonished when, as he was detoxing from drug and alcohol abuse in a clinic, a cheque arrived from Monkhouse, along with a funny and touchingly inspirational message (apologising for the 'cheeky intrusion') expressing his deep concern. They had only met once, twenty years before, but Monkhouse had remembered him and, once he heard of his current plight, had tracked him down to offer help.

As soon as the man was back out and had regained his health, Monkhouse arranged for him to do the voiceovers for one of his quiz shows, and made sure that his name was networked around the industry.

It was merely what Monkhouse was like. He never forgot anyone or anything, he loved encouraging other people, and he always noticed when someone was in need. Even when he knew that he was dying, he was still busy trying to find the best way to boost the morale of, amongst others, a veteran comedian, Mike Yarwood, and an up-and-coming one, Ricky Grover, by getting them involved in what he knew would probably be his final shows.

One of his favourites of the many TV series that he made was the one that he did for the BBC during the 1980s, The Bob Monkhouse Show. He liked it so much, he said, because it gave him the opportunity to celebrate those of his fellow comedians whom he admired the most, and heighten the profile of those whom he wanted to see reach a bigger and broader audience.

Robin Williams was a guest, as were Steven Wright, Jim Carrey, Les Dawson, Bob Elliott and Ray Goulding, Peter Cook, Spike Milligan, Joan Rivers, Phyllis Diller, Tommy Cooper, Frankie Howerd, Emo Philips, Bill Maher, Sid Caesar and Victoria Wood. Those critics who accused him of sycophancy on the show completely missed the point, because, in his usual unselfish way, he simply wanted to do what he could to make those who were good look good.

It was no great coincidence that the contemporary who approached his own show in a similar manner was Des O'Connor (on Des O'Connor Tonight), because he was always shaped by a similar generosity of spirit. He had been one of the first celebrities, apart from Ernie Wise, who reacted when Eric Morecambe suffered his first heart attack, telling his ailing friend that in concert the following evening he had urged the audience to pray for him - thus inviting the affectionate put-down from Eric: 'Those six or seven people might have made all the difference'.

He was, in fact (as Morecambe well-appreciated), delighted whenever he could cue such a quip from a comic. Indeed, one of the least-publicised aspects of his long and distinguished career was his role as a facilitator of other people's fame. An example is the part that he played in promoting the career of Jack Douglas.

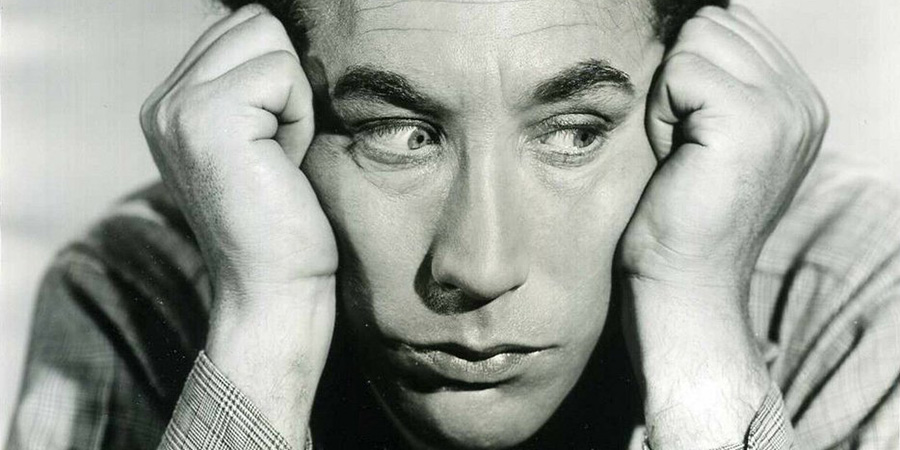

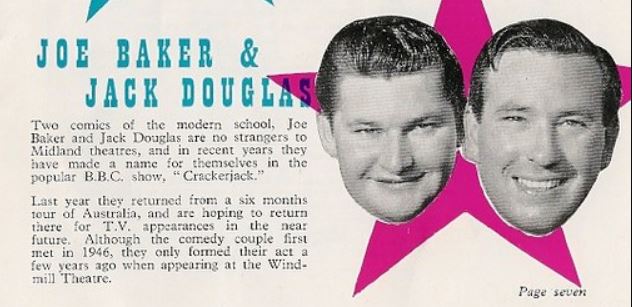

Douglas was one half of quite a successful double act with Joe Baker when, in 1962, the latter decided to leave to try his luck as a solo performer in America. After a decade of duty as a straight man, Douglas suddenly found himself stranded.

Although he went on to work every now and again with a number of well-established comedians (including Bruce Forsyth, Arthur Haynes and Arthur Askey), he realised that being a freelance straight man hardly promised a stable and secure future, so he told his agent, Leslie Grade, that he wanted to become a comic. Grade merely said to him, 'You don't look funny', and tried to persuade him to carry on being a feed.

Douglas, however, was adamant: 'Leslie,' he said, 'if I can't become a comic I'll quit show business.' Grade replied, 'Oh, you'll never do that,' but that is exactly what Douglas did. A keen cook, he opened a pub/restaurant in Blackpool (the Winmarith - nowadays known as the Spen Dyke - on Lytham Road), lived over the top of it, and busied himself with running it.

'I'd been doing that for about six months,' he would later say, 'when I got a phone call - I seem to remember it was in the middle of the night - from Des O'Connor. "Would I come back," he asked. So I went back.'

O'Connor was booked to make thirteen shows for ATV, starting in May 1963, in his first series as a star, and he made it clear that he wanted Douglas to be a regular participant. 'What do you want me to do?' Douglas asked. 'Whatever the bloody hell you like,' O'Connor replied.

Seizing on the chance to prove himself as a comedian, Douglas devised the character of Alf Ippititimus, a northern labourer, dressed in a cloth cap, steel-rimmed spectacles, blue denim overalls and big black boots, whose abrupt, noisy and violent twitches - 'Whu-haaaay!' - were a bit like an act of self-mugging. One second he would be talking in that deep drawl of his, and the next he'd be off - 'juh-hur-whu-huua-phwah-whu-haaaay!' - spinning round to the right, to the left, and then, with a quick adjustment of the cap, he would resume his conversation.

For his first appearance in character, he strode on in front of the camera looking as though he was a stage hand about to effect an urgent repair. 'Mr O'Connor?' he said, looking slightly disoriented under all of the lights. O'Connor said, 'What's your name?' Douglas said, 'Alf Ippititimus'. O'Connor said, 'Ippiwhatamus?' Douglas replied, 'No, Ippititimus'. O'Connor asked, 'How do you spell it?' Douglas answered, 'Two ipps, a pip and a titimus'. The character was an immediate hit, and O'Connor was delighted.

'I must say the most unselfish comedian I've ever worked with in my life,' Douglas would later acknowledge, 'is Des O'Connor, because the more laughs I got, the happier he was.'

Their relationship, on stage and off, became so strong that they continued working together, on and off, for the next few years, at venues all over the world. O'Connor swiftly established himself as one of British television's most popular entertainers, as well as quite a successful recording artiste, while Douglas remained at the more modest level of a 'supporting' comic performer, but O'Connor never treated - and made sure no one else ever treated - his friend as anything other than an equal.

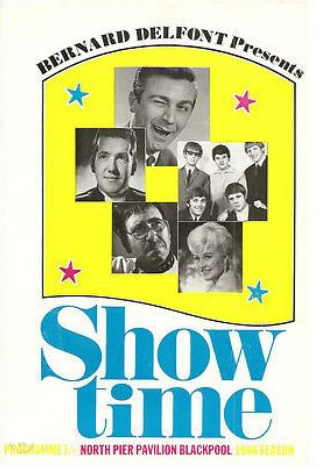

They were appearing together at the North Pier Pavilion in Blackpool during the summer of 1966 when there was a knock at their dressing room door. Douglas opened it and there was the boss of the show, the impresario Bernard Delfont. 'I'm popping in to see Des,' Delfont said. 'Nice to see you, goodbye,' and Douglas found himself stuck outside as Delfont passed him to go inside and shut the door behind him.

Intrigued, Douglas tip-toed off, got a glass, tip-toed back, held it up to the door and started eavesdropping. What he heard was Delfont saying, 'I want you to do the Royal Variety Performance for the Queen Mother this year, Des,' and then Des O'Connor replying, 'Oh, wonderful, Mr Delfont, thank you'.

Delfont went on: 'But instead of you doing one half of the show and another comic doing the next half of the show, I want you to host the whole show.' O'Connor thanked him even more effusively, but then said, 'I'd like to use Jack'. A surprised Delfont replied, 'Well, you'll be compèring the show - you don't want anyone else on it with you, they could steal your applause'.

O'Connor answered, 'Mr Delfont, when Jack comes down in the finale, does he go better than me?' Delfont said, 'No, of course he doesn't'. So O'Connor said, 'Fine. Well, then, I'm having Jack on the show'.

The two men went on the show together and performed several warmly-received routines, with O'Connor proving an expert feed to Douglas's comic turns. 'It's about time,' one critic would write at the end of that night, 'Douglas was recognised as one of our funniest comedians,' while another said that the 'stooge became a star [...] poaching the longest laughs of the show'.

After the performance, back in the dressing room, the two of them were relaxing when Robert Nesbitt, the show's producer, rushed in to tell them to get changed and join the line-up to meet the Queen Mother. O'Connor said, 'Hang on - if Jack gets changed, nobody will know him, because they don't know his face'. The producer looked at Douglas, still in his dirty overalls and big boots, and exclaimed, 'Well, he's certainly not meeting the Queen Mother dressed like that!'

So O'Connor replied, 'Mr Nesbitt, if Jack doesn't meet the Queen Mother, neither do I'. Alarmed, Nesbitt stuttered, 'B-But, you can't do that, you-you've got to-' and O'Connor replied, 'No, I don't - either Jack meets the Queen Mother with me, or I don't meet the Queen Mother at all'. Nesbitt, not knowing what else to do, relented and walked off.

Douglas, still dressed as Alf Ippititimus, duly met the Queen Mother. Standing next to a beaming O'Connor, he took off his cap as she approached and tucked it under his belt, ready to shake her hand. 'You may not be the smartest man here this evening,' she said with a smile, 'but you're one of the funniest.'

Douglas would never forget the loyalty and support O'Connor showed him during their time together. 'Quite simply,' he said of his friend and erstwhile partner, 'Des is one of the kindest, most thoughtful and most decent men in the business.'

In a suitable karmic spirit, Jack Douglas would behave just as well himself throughout his own comic career. His kindness towards Terry-Thomas, in particular, was typical of his compassionate nature.

Privately diagnosed with Parkinson's disease in 1971, Terry-Thomas had struggled through several more movies - including Spanish Fly (1975), The Last Remake Of Beau Geste (1977) and The Hound Of The Baskervilles (1978) - before his physical symptoms became so noticeable that he made his condition public, recording an appeal for the Parkinson's Disease Society that was shown on BBC TV in 1977.

By the late 1980s, long after the work had stopped, the cost of medical bills had forced him to sell his homes in Ibiza and London, and he and his wife and two children moved, via a church-linked housing association, to a small, three-roomed, unfurnished flat in a property in Barnes. Now gripped tightly by the debilitating disease, the once-indefatigably ebullient T-T sat dimmed and drained in the shadows.

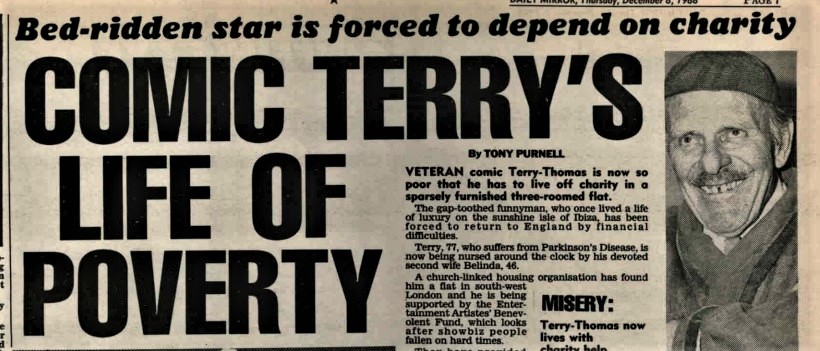

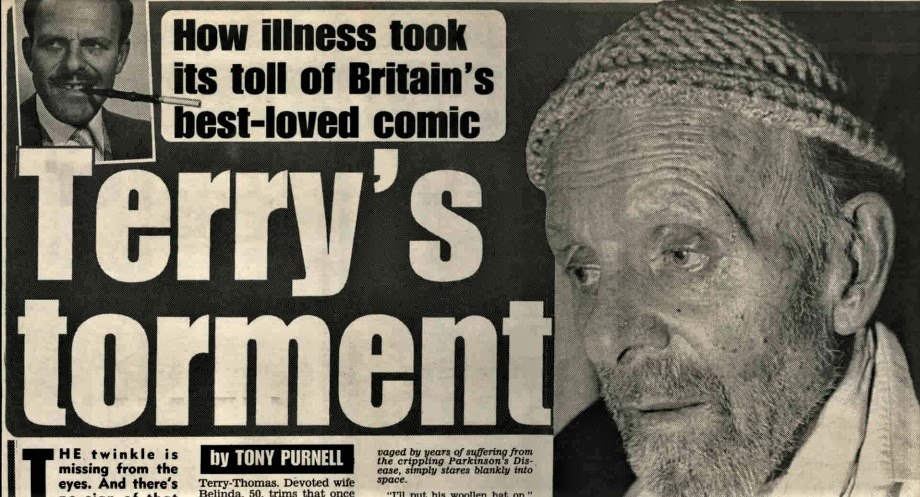

The Daily Mirror, upon discovering his pathetic plight, carried an article bearing the headline: 'Comic Terry's Life of Poverty'. The piece - published in December 1988 - told the story of how the actor was now practically bedridden and living hand-to-mouth in South-West London. 'It is very sad,' a representative of an actors' charity was quoted as saying; 'he is in a very bad way.'

The paper returned to the story the following morning. Beneath a photograph of the seventy-seven year-old actor looking grey, glazed and gaunt with an untidy beard and a shapeless woollen hat, the report revealed that 'the former funny man' now 'simply stares into space' for much of each day, warmed by a one-bar electric fire, while being cared-for round the clock by his wife. It was said that she no longer shaved her husband because she had grown too afraid of cutting him as he shook, and, now that her own back was weak from lifting him in and out of bed, she dreaded him taking a fall. Underlining just how impoverished the couple had become, the article pointed out that any hot water had to be boiled in an old saucepan because they did not even own a kettle.

Much was made of the fact that Terry-Thomas had apparently been either forgotten or abandoned by so many of his fellow stars. The newspaper noted that, apart from his ever-loyal cousin Richard Briers and his old friend and colleague George Cole (both of whom had visited several times and offered their enduring assistance), there had been no contact with other celebrities. 'I'm sure there are lots of friends who are unaware that we are even back in England,' his wife was quoted as saying. 'A lot of them must have thought Terry was dead.'

The response was immediate. The Daily Mirror, with traditional tabloid self-effacement, trumpeted the news that the show business world had been 'stunned' by its 'exclusive' story that 'the film world's upper class gent is sadly on his uppers', and that various celebrities had started sending in cash and offering help. 'I thought he was still comfortably off and still living in the Spanish sunshine,' Bob Monkhouse was reported as saying, as he contributed £1,000. Michael Winner, one of T-T's old directors, donated £250 and a few kind words, while, in America, Mickey Rooney spoke on behalf of the Hollywood community when he expressed his concern for 'one of the greatest purveyors of laughter there's ever been in the history of the motion picture business', and promised some concerted support.

The Mirror, meanwhile, managed to find enough spare cash in its budget to buy the ailing star six pairs of woollen socks, a two-slice toaster and a brand new electric kettle, and then launched an appeal for further financial assistance from among its predominantly working-class readership.

The prospect of an additional source of support arose early the following year, when a lifelong admirer of T-T's, the writer and broadcaster Richard Hope-Hawkins, travelled to visit him and was shaken by what he saw. Later that same day, Hope-Hawkins went on a pre-arranged visit to see some friends who were appearing in a show at the Arts Centre in Horsham, and his distress was still evident to everyone there whom he met. 'All of them - Ed Stewart, Peggy Mount, Jack Douglas and the others - said, "What on earth is wrong with you, Richard?"' he would recall. 'I tried to avoid saying anything, but Jack insisted, so I told them where I'd been and what had happened.'

Alarmed by what he heard, Jack Douglas then asked Hope-Hawkins to take him to see T-T as soon as was possible, so another trip to Barnes was duly arranged. Douglas came close to tears when he saw what had become of the individual whom he, like Hope-Hawkins, still considered a huge personal hero: 'He was wearing a balaclava and an army greatcoat, which completely swamped his now emaciated frame'.

There was no hope of a conversation, so Douglas just knelt down, took hold of one of his fellow actor's frail and clammy hands and talked to him while searching for the occasional flicker of recognition in his dark and rheumy eyes. When the meeting was over, Douglas just managed to make it back out the door before breaking down in tears, asking Hope-Hawkins: 'How could a man like Terry, who'd brought such pleasure to millions of people, have ended up like that?'

Once back in their respective homes, the pair called each other and resolved to do what they could to help. 'You've got an idea, haven't you?' Douglas remarked. Hope-Hawkins said that he did: 'I've never done anything like it before, but why not have a gala and raise some money for Terry-Thomas?' The pair agreed to proceed.

Hope-Hawkins later told me: 'I rang ITN - Jack was involved in this as well, of course - and said, "Will you come and film Terry-Thomas?" But I added: "There's one proviso: we only want one film crew in with Terry. So you must syndicate it." They agreed. So I drove from Bristol to Terry's flat in Barnes and we filmed it, and, of course, it really took off after that. The footage went all over the world.'

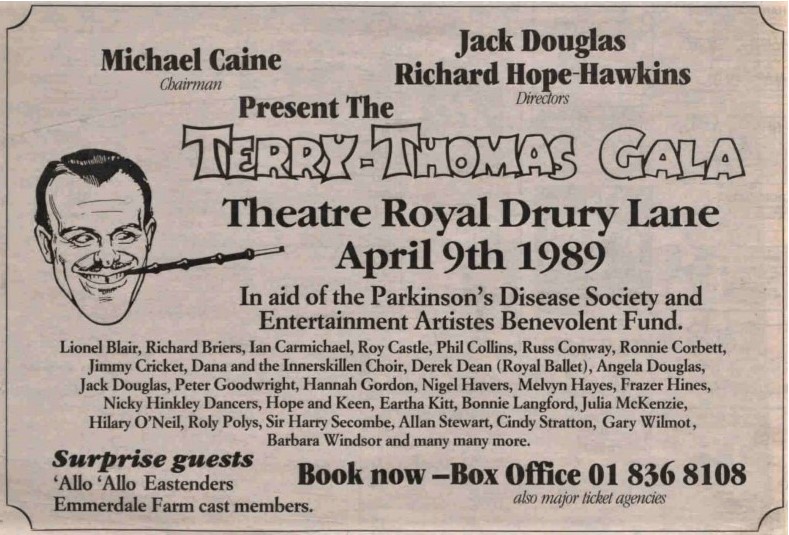

Jack Douglas, in the meantime, had made contact with the hugely influential agent Dennis Selinger, and asked him if he could come up with a star big enough to act as a figurehead for the fund-raising project. 'Is Michael Caine big enough for you?' asked Selinger rhetorically. Douglas was delighted.

Douglas and Hope-Hawkins then called on John Avery, who was the current head of the Moss Empires chain, and suggested staging a high-profile charity show. Avery agreed, promptly made the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, available at no charge ('If it's for Terry-Thomas, it's for free') and told the pair of them to go ahead and start assembling a cast.

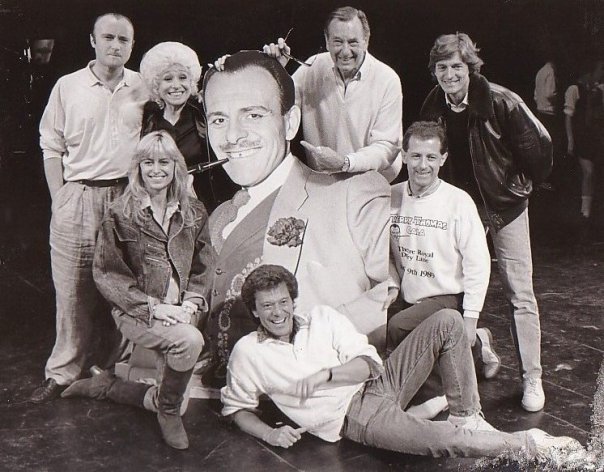

It did not take them long to enlist the services of a large and eclectic collection of British-based performers - ranging from a coterie of old friends and former colleagues (such as Richard Briers, Harry Secombe, Ronnie Corbett, Barbara Windsor, Lionel Jeffries, Eartha Kitt, Janet Brown, Ian Carmichael, Angela Douglas and the re-formed Tiller Girls troupe) to a mixture of recent and longstanding fans (including Nigel Havers, Susan George, Kit and the Widow, Peter Goodwright, Julia McKenzie, Russ Conway, Hannah Gordon, Roy Castle, various cast members from 'Allo 'Allo!, EastEnders, Emmerdale and Coronation Street and one of the biggest international pop acts of the time, Phil Collins). They also quickly attracted the attention of the national media, and, once Michael Caine had agreed to act as the chairman of the organising committee, the interest extended far across the Atlantic.

On the evening of 22nd March, several old friends and former colleagues gathered together at one of T-T's favourite American places, the very English-style King's Head pub in Santa Monica, and recorded their warmest wishes for him. Appeals were broadcast, messages of support were circulated and donations despatched. Fans in France, Italy, Spain, Germany, South America, Australia and elsewhere expressed their urgent concern. 'It was wonderful to find out just how much so many people genuinely cared about Terry,' Hope-Hawkins would recall. 'He was universally loved.'

Directed by Jack Douglas, The Terry-Thomas Benefit Concert took place on Sunday 9th April 1989 in front of a full house of 2,387 people. In addition to the more than one-hundred-and-fifty stars (both advertised and unbilled) who were present on the stage, the event also promised recorded contributions from the likes of Michael Caine, Jack Lemmon, Julie Andrews, Dudley Moore, Roy and Karen Dotrice, Mickey Rooney, Lynn Redgrave, Milton Berle, Ken Annakin, Glynis Johns and Shirley Anne Field.

'On the night,' Hope-Hawkins would recall, 'it was like the premiere of a big Hollywood movie. You really couldn't move outside in the street.' Some of those who appeared inside up on the stage simply wanted to underline how much T-T still meant to them. The actor Melvyn Hayes, for example, recalled one particular private act of kindness:

Twenty-five years ago, I had a very bad accident. I was knocked down by a car and smashed up. And I was lying in hospital, my personal life was in a terrible mess and my body was in a terrible mess, and I was in traction and I'd got pneumonia - I was in a terrible state. And I'd been like this for two months when the phone rang by the side of my bed. And I picked up the telephone and a voice said: 'Hello, my name's Terry-Thomas, you don't know me, but I understand you need cheering up a bit. So what do you want to talk about?' And for about half an hour he gave me a one-to-one cabaret. He told me some of the funniest things and it was hysterical. Nobody knew about this except me and him. And at the end of half an hour he said: 'Well, I hope I've brought a little bit of happiness into your life'. And I'd just like to say: Terry, it's taken me twenty-five years - I've not had the opportunity - to say, 'Thank you'.

Most of those performers who participated enjoyed being part of the occasion so much that they overran by several minutes each, thus causing the event as a whole to continue far beyond the end of its official schedule: 'At about a quarter past midnight,' Hope-Hawkins would recall, 'Phil Collins got on stage and said, "I've shaved three times since I arrived in the theatre!" And then he was the last act on stage'.

The subject of the tribute, though sadly not well enough to attend, was shown a special video of the concert soon after. He watched it with tears rolling down his otherwise expressionless face.

The production raised over £75,000 (more than £200,000 by today's value), and the subsequent television tribute added another £23,000, all of which was shared out between the newly-created Terry-Thomas Trust and the Parkinson's Disease Society. It enabled T-T to start living in comfort at the £200-per-week Busbridge Hall Nursing Home in Godalming, Surrey.

'I went to see how he was settling in,' Jack Douglas recalled, 'and found him sitting up in a comfortable bed wearing a smart red-check dressing gown. I took hold of his shaky hand and was relieved to discover that this time it felt warm, instead of icy cold.'

Something, at last, had been done. 'This is to pay you back for all the laughter and entertainment you've given to us over the years, Terry,' said Douglas, who then added: 'But no chasing these nurses, mind.' T-T remained silent, staring ahead, but, after a while, Douglas felt that he understood: 'He gripped my hand and smiled with his eyes'.

It was interesting that such kindness received far less press coverage than the plight to which it responded. Decency, alas, is rarely deemed newsworthy. It is good to be reminded, however, that the quality is still very much around in comedy, even if some, during their day job, prefer to keep it a secret.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more