The ever-intriguing Fenella Fielding

If you were to ask any British comedy fan of a certain age if they remember Fenella Fielding, they would almost certainly say yes without the slightest hesitation. If, however, you were to go on to ask them to name more than a couple of things that they remember her actually being in, they would probably find it quite a struggle to respond.

This is the odd thing about Fenella Fielding. For more than half a century, she seemed to keep flitting in and out of the spotlight so frequently but so swiftly that she made a name for herself without ever finding a place for herself.

There was not the steady run of movie roles that, say, Barbara Windsor or Joan Sims enjoyed. There were not the regular and prominent television appearances that the likes of June Whitfield or Wendy Craig were experiencing. Audiences felt that they knew and liked Fenella Fielding in spite of the strange elusiveness of her presence.

Her sultry, saucy, slyly subversive voice could be heard in countless commercials (everything from OMO soap powder to Carson's liqueur chocolates, from Bel Air hairspray to BP 'super performance' petrol), but slipped away again just as quickly as each campaign concluded. Her 'catty-foxy' features (as she herself described them) could be seen in numerous TV shows (ranging from Danger Man and The Avengers to Call My Bluff and Comedy Playhouse), but they were usually one-off appearances that, in the days before home recording, evaporated straight up into the ether.

The most abiding and iconic image of Fenella Fielding comes, of course, from that famous scene in Carry On Screaming! (1966), when, as the voracious vamp Valeria, she appeared in a long, low-cut, red velvet dress, reclining on a chaise-longue as clouds of dry ice billowed around her breasts, and inquired of her startled visitor: 'Do you mind if I smoke?' For the rest of her life, right up to her ninetieth and final year, people would keep asking her to say the line again just for them.

There was, however, so much more to Fenella Fielding than that one film and famous phrase. She was a very intelligent, versatile and deeply distinctive character whose elusiveness, compared to the ubiquity of some of her peers, made her even more of an intriguing figure.

Born Fenella Marion Feldman in Hackney in 1927, the youngest child of a Romanian mother and a Lithuanian father, she had endured a difficult upbringing. Unlike her elder brother Basil (who grew up to be the businessman and Conservative Party peer Baron Feldman), her relationship with her snobbish and self-obsessed parents was never easy, frequently strained and sometimes alarmingly violent.

As a young child, she seemed to speak in little more than gibberish; indeed, her mother and father feared that she was failing to develop basic language skills until they chanced upon her one day in animated conversation with a doll. 'I suppose,' she later wrote, 'I just didn't want to speak to my parents'.

Both of them bid to block her whenever she aired any independent ambition. She managed a spell at RADA, only for her mother to cut her stay cruelly short ('Really, darling, these people...these common people...'), and she spent a few months studying at St Martin's School of Art, only for her father to do the same ('I don't think you're going to go on with this'). When she attempted to apply to university, her father flatly refused to let her even send in her forms ('I'd rather see you dead at my feet').

Perversely, her parents intervened even when she followed their own plans for her future life. They sent her to learn secretarial skills at Pitman's, the business school, with a view to her finding a role in an office somewhere, but then became impatient for her to start work, and so they dragged her back out long before her training had been completed. 'It was so depressing,' she would reflect, 'to think that I wasn't even a competent shorthand typist'.

Whenever she tried to rebel against the draconian parental rules, her father (whom she later described as a 'street angel and house devil') would simply beat her with his fists, while her mother, she said, 'would egg him on'. It was hardly much of a surprise, given these circumstances, when she ended up attempting suicide by swallowing 'about seventy aspirins'.

Even this failed to crack the carapace of coldness that her parents kept hiding behind. 'They never mentioned the incident to me afterwards,' she would recall, 'but part of me would have liked them to have said, "How awful it would have been if you'd died"'.

She ran away, inevitably, as soon as she possibly could, found a flat, changed her surname to 'Fielding' ('I thought it sounded crisper, better...and it was a new start'), and commenced her acting career. There then followed a succession of poorly-paid and lowly-rated jobs in cabarets and chorus lines until, at the end of the 1950s, she got not one but two big breaks in quick succession.

The first came in 1958 when she was cast in the Sandy Wilson satirical musical Valmouth. She played Lady Parvula de Panzoust, a hobble-skirted man-eater of uncertain age who is intent on seducing a simple shepherd. Considered a rather unrewarding part on paper, Fielding (in what was described as 'the most audacious piece of show-stealing for years') surprised the critics with her energy, wit and invention, prompting one of them to praise her for pursuing her prey with 'the comic concentration of a lovely and lithe Siamese cat'.

The following year, she was co-starring alongside Kenneth Williams in the revue Pieces Of Eight. Written chiefly by the precociously brilliant Peter Cook (who was still a student at Cambridge at the time), with other contributions from Harold Pinter, John Law and Lance Mulcahy, the sketches were refreshingly sharp, literate, and youthfully irreverent, and the production - a harbinger, really, of the next decade's satirical era - was predicted by one newspaper to become 'one of the highlights of the year in the theatre'.

It was this step towards stardom, however, that led to Fielding experiencing the less salubrious side of show business. Kenneth Williams, by his own admission, 'never got on with actresses' (with one or two exceptions), and he did not get on with Fielding to such an extent that he made her life a misery.

Insecure about how the show would go now that he finally had his name in lights above the theatre, he was nervous and irascible from the start, and saw his co-star (whom, resentfully, he took to calling 'Madam' or 'La Fielding' or sometimes even 'It') as a potentially hazardous variable in a production he was keen to control.

Having already been rattled merely by the fact that she had asked for, and been granted, star billing alongside him, Williams retaliated by ensuring, unofficially, she would not have 'co-star rights' (meaning that, while he could veto whatever material he disliked, she could not). This resulted, predictably, in Williams keeping those sketches that suited his strengths, and losing those ones that he suspected might suit the strengths of his co-star. Fielding was thus left furious: 'Every bloody thing that I thought I would like, Kenneth has said no to, but I hadn't been told'. The gloves, therefore, were already off before the production had even reached the stage.

Round two commenced during rehearsals, when Williams did his best to render her a nervous wreck. First he would urge her to ad-lib more, and then complain to the director that she was improvising too much. Then he would tell her to stick rigidly to the script, and then complain to the director that she was a slave to the written material.

Round three of the tussle began when the show started its try-out run outside of London. While the critics were in general very kind to Kenneth Williams, many of them were even nicer about Fenella Fielding. The positive comments kept on coming: 'delightfully vivacious'; 'sly and sexy'; 'warm and vital'; 'an actress with a flair for the satirical'; 'as soon as she comes upon the stage she casts a spell'; 'a beautiful butterfly of comedy'; and 'a fascinating new star in the making'.

Williams took it badly - very badly. He not only arranged for a couple of friends to criticise her performances loudly outside the theatre, directly above her basement dressing room window, so that - he hoped - she would hear it and her confidence would be crushed, but he also started shrieking insults at her in rehearsals and sometimes in breaks backstage during shows, frequently reducing her to tears. 'I wouldn't have thought,' Fielding later said, 'anybody could be so open about it as to say the things he said to me.'

The next stage in the conflict occurred on the eve of their West End debut. Although by this stage Fielding, feeling harassed and helpless, was doing her best to avoid him ('I thought, God! I can't help the fact they've said something nice about me'), Williams sought her out, produced a number of press cuttings from his pocket, read out all of her critical praise in his most nasally withering tones, and then threw them aside, exclaiming, 'It's outrageous!' Things then turned more sinister, with Williams coming closer, warning her 'not to be too successful'. Fielding was genuinely alarmed by the air of menace in his voice: 'I've never been so frightened in all my life.'

The West End run went on, and on, and so did the tensions both on and off the stage. Sometimes, for example, Williams would ad-lib a line, get a good reaction, and the two of them would keep it in for the following evening, but if Fielding ever did the same, she would find the next night that Williams would either leap in and pinch it for himself or else deny her the cue to say it. Then there were the days when Williams would conserve his energy by leaving his co-star to carry the matinée performance, and then he would suddenly snap back into forceful action for the second show, shouting over her lines and doing whatever he could to exploit her exhaustion. It was a relentless campaign of intimidation, and Fielding would later say that she spent most of the period in a desperate state, 'crying my eyes out the whole time'.

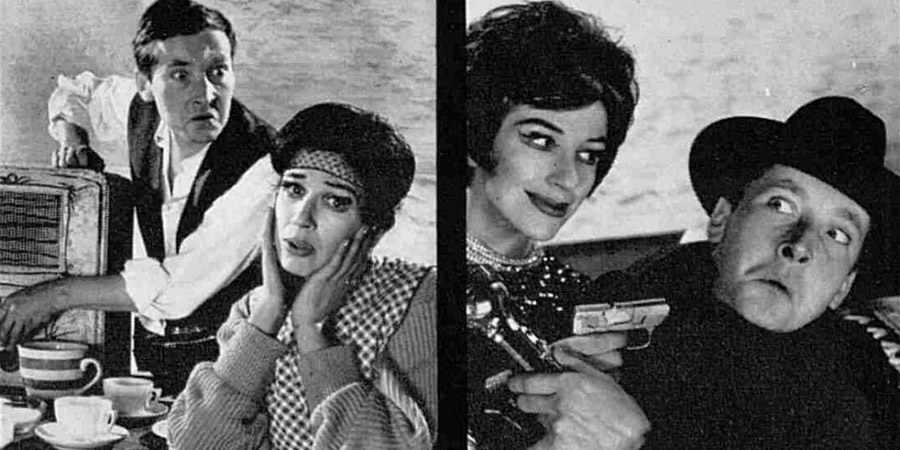

Things came to a head one evening, during a performance of a darkly comic sketch in which Williams and Fielding, rather aptly in the circumstances, played two ultra-competitive spies, whose succession of boasts and counter-boasts culminated with a challenge to see whose secret poison would produce the quickest suicide. After they both downed their respective draughts, Williams's character was supposed to die first, but, on this occasion, he doggedly refused to keel over, staggering around the stage using various comic voices in the hope of leaving Fielding looking helpless. Eventually, however, she decided to take charge of the situation, shouting out 'Last one dead's a sissy!' and falling down herself.

It got a huge burst of laughter and applause from the audience, and the curtain came swiftly down. After the show, however, Williams was incandescent with rage. 'She called me a homosexual,' he screamed at the management, 'in front of the whole audience!' She had not meant anything of the kind, but he seized on it as a sign of her 'poisonous' attitude.

After that, there was no hope left. 'He wouldn't speak to me,' Fielding would reveal. 'It was really foul'.

She tried to get out of the production, but she was needed, and so she stayed. Williams, himself utterly sick of the situation, came and went each night without acknowledging her existence. She sat alone in her dressing room, spending most of the time in tears, and the experience would scar her for life: 'I used to be innocent. I used to be trusting. But after eighteen months of that...'

Once it was all finally over, they gratefully went their separate ways, both of them hoping never to work with the other one ever again. Then, in 1966, they discovered that they were set to act alongside each other again in the movie Carry On Screaming!, with Fielding playing the predatory, pink-petalled-cheeked, sexually intoxicating Valeria, and Williams her snow-faced, wide-eyed and repeatedly jump-started undead brother, Dr Orlando Watt (HIM: 'What time is it?' HER: 'Just past December').

Neither of them, to put it mildly, were looking forward to the reunion, but, much to their mutual surprise, they ended up getting on rather well. Williams, to begin with, was merely reserved and coldly professional, but Fielding decided to take the initiative, disarming him by behaving so eccentrically that, while he could not work out what on earth she was actually doing ('She is such an enigmatic creature,' he wrote in his diary), he could no longer see her as a threat.

There was one moment, midway through, when she won him over completely. They were filming outside on location, sitting close together inside a vintage car. Suddenly, just before a take, she turned to him and said, 'Why is your bum so hard? Do you leave it out at night?'

His brain quickly buzzed through the states of surprise, alarm and bemusement, and then, wide-eyed, he collapsed in a fit of giggles. 'I went to her dressing room afterwards,' he would say, 'and told her truthfully, "I haven't laughed so much for years"'.

After that they were fine. 'We used to sit and gossip between shots,' Fielding later revealed.

The role, regardless of their relationship, was a near-perfect one as a showcase for her distinctive comic gifts. Parting her long dark hair away from her body like a curtain revealing a play, she dominated every scene, seizing on a script pumped full of the saltiest of innuendos ('Bung? That's a very fitting name!'), and provided the Carry On format with an attractive female figure who was refreshingly smart, self-assertive and very much in control ('I am your mistress!').

The critics, once again, loved her, and predicted bigger and better starring roles for her in future movies, but then Fielding, once again, seemed disinclined to pursue such a populist path. She chose instead to record a new production of Sheridan's classic comedy of manners The Rivals for radio, pop up on the odd TV chat or panel show, make a few personal appearances for BP, provide some voiceovers for The Prisoner and do more work in the theatre (starting with the Victorien Sardou play Let's Get Divorced, which she would regard as 'the moment when I really got my acting badge').

Her apparently unmethodical approach puzzled plenty of people in the industry. Indeed, when she was a guest, in 1967, on the BBC's Desert Island Discs, the presenter Roy Plomley, in the manner of a somewhat disappointed headmaster, echoed many when he observed: 'Your career hasn't had a very definite pattern, has it? In fact, it seems you've rather fought against it taking a pattern.' Fielding, however, was unapologetic. She had decided, she said of the peculiar course of her career, 'that if anything was going to make it change, I must make it change'.

The truth was that, while always eager to test her talents, she was never driven purely by any deep desire to be a star - at least not in any simplistically conventional sense of that term. She had previously turned down the lead role in Carry On Cleo, for example, because she preferred to spend time with a boyfriend in New York. She would also soon pass on the chance to work with Federico Fellini on an unnamed project because, after hearing rumours about how he would sometimes be captivated by certain actors only to become bored with them a few days or weeks later, she got 'a bit scared' and stuck with her existing stage commitments instead.

So what did she do while others were chasing fame? She enjoyed herself a great deal. She certainly enjoyed herself socially and sexually, making a point of being the one who controlled each situation.

Socially, she became one of the signature people of Sixties London: a regular client of Vidal Sassoon, Mary Quant and Biba; a familiar fixture at The Establishment, Ronnie Scott's and the Colony Room Club; photographed by David Bailey, Lewis Morley and Terence Donovan; and mixing with the likes of Paul McCartney, Francis Bacon, Cleo Laine and Kenneth Tynan. The gossip columnists loved her - one of them dubbing her 'the wittiest woman in London' - and lauded her as one of the most glamorous role models for a new generation of fashionable, free-thinking, free-spirited female figures.

Sexually, she was equally à la mode. On one sultry summer's afternoon, for example, the notoriously louche journalist Jeffrey Bernard arrived at her apartment to interview her for an upmarket magazine profile. After listening to her voice for a few minutes, he closed his notebook and declared solemnly that he could not possibly continue. 'Why not, darling?' she asked, fluttering her long and spidery coal-black lashes. 'I just can't concentrate,' he complained. 'And why's that?' she said with the arch of an eyebrow and a playful scarlet-lipped smile. 'Because all I'm doing is sitting here thinking how much I'd like to fuck you'. Now grinning, she replied: 'And so you shall, you silly boy,' and led him off calmly to bed.

She also had a satisfyingly vindictive strategy if she ever found that a lover had dared to be unfaithful. She would visit his flat when he was out, enter his bedroom and pour a whole bottle of her very distinctive perfume all over his mattress and carpet, thus sentencing him to months of being asked: 'Who on EARTH have you had in here?'

Her career, meanwhile, was gradually being undermined by the fact that she was currently being 'guided' by an agent who, slowly but surely, was swindling her out of increasingly large amounts of her earnings. By the time that she finally realised what had really been happening, she was broke, had to sell her home, and was left alone, feeling utterly humiliated as she was forced to go on the dole. 'It's rather awful sitting in a room waiting for benefits and everybody knows who you are,' she would recall. 'I had a terrible feeling I was finished. You've gone from this to that, and it's just like you're a failure. You think: what happened? Wow! WOW!'

She eventually found a trustworthy agent, and began to slowly rebuild her finances and career, but she remained far more wary than most of her peers about what passed as the show business world. She had been hurt once, and she was determined not to be hurt again.

Sexism was one hazard she was not prepared to accept. For much of her career so far, Fielding had to contend not only with the kind of misogynistic verbal aggression exemplified by the acidulous Kenneth Williams, but also with the physical attacks that, in those days, were routinely excused and explained away (when 'stars' were involved) by the industry's powers that be. 'There was a time when every man I met,' she said sadly, 'was really something horrid.'

When, for example, she worked with Norman Wisdom on Follow A Star (1959), she had been left on her own to defend herself against his repeated attempts at not so much seducing as assaulting her. 'Not a pleasant man,' she later said of him with over-generous understatement. 'Always making a pass - hand up your skirt first thing in the morning. Not exactly a lovely way to start a day's filming.'

It happened on several other productions over the years, and, while she was very adept at evading advances ('You had to make sure you nipped about a bit'), she grew understandably sick and tired of being expected to navigate her way around such masculine nonsense.

Pigeonholing was another problem that increasingly strained her patience. Offers of roles would keep coming in, usually from low-budget producers, for under-written roles that were often only described in terms of a type: 'the vamp'; 'the femme fatale'; 'the nymphomaniac'. 'I'm just sick of being looked at in that particular way,' she eventually told her agent, 'for the same kind of parts.'

Even some women seemed disinclined to see her except through the prism of prejudice. The novelist Doris Lessing, for example, watched her in the West End give a critically-praised performance in Hedda Gabler and declared afterwards, 'Fenella, you don't know what you're doing there on stage. It's so marvellous.' Fielding - who always knew exactly what she was doing with a performance - angrily dismissed the patronising comment as belonging to 'the department of fucking cheek'.

Determined to do only those projects that interested her rather than any of her supposed admirers, she picked and chose her roles and productions in terms of their depth and diversity. She relished radio especially because, without the distraction of her looks, she felt able to use the full range of her skills, so she worked regularly in the medium, appearing in plays by, among others, Noel Coward, George Bernard Shaw, Emlyn Williams, Alexander Ostrovsky, Isaac Babel, Chekhov, Michael Frayn, Charles Dickens and Shakespeare.

She would still accept invitations to appear on television, but only if her contribution was treated with proper respect. The Morecambe & Wise Show (clip), for example, became a favourite engagement (she appeared in it no fewer than four times) because its stars were always so keen to collaborate with her as equals: 'Morecambe and Wise were different,' she would reflect. 'They did want you to show them off, but they wanted you to show yourself off, too. They wanted you to be ever so good, so they made sure that you had jolly nice parts.'

Most of the time, however, she stayed away from the screen, and, as a result, while some of her contemporaries were consolidating their fame by fighting to remain as visible as possible, moving from one sitcom or drama series to the next, Fenella Fielding, as the years went by, grew curiously obscure - and it seemed to suit her.

In her later years, she was, true to form, still very busy in an elusive sort of way, doing a dazzlingly wide variety of things without ever pausing very long to pose in the public eye. She taught some drama sessions at London's City Lit; recorded some remarkable readings of literary classics (including a collection of pieces by Colette, TS Eliot's Four Quartets and JG Ballard's Crash); contributed a quite extraordinary covers album (The Savoy Sessions) that re-styled contemporary songs ranging from an entertainingly evocative interpretation of New Order's Blue Monday to an hypnotically effective but hilariously disdainful cover of Public Image Limited's Rise; worked alongside Rik Mayall and Adrian Edmondson in the movie Guest House Paradiso; made a cameo appearance in Channel 4's teen drama series Skins; and provided humorous readings for the intervals in a BBC Radio 3 broadcast of Die Fledermaus.

As far as public appearances were concerned, she found time to appear in and tour with numerous plays; occasionally consented to a few low-key one-woman shows; performed, quite beautifully, some adapted translations (by David Stuttard) of Greek classics, including a particularly moving reading of Hekabe from Euripides's The Trojan Women; and accepted an invitation from Jarvis Cocker to appear in his 2007 curation of the London South Bank Meltdown festival.

She also, thanks to the kind and caring assistance of her friend and Pilates partner, the psychotherapist Simon McKay, finally got round to publishing a memoir, with the inevitable title of Do You Mind If I Smoke?, in 2017. Stylishly presented, and structured in themes rather than chronological sections, it was full of endearing and teasingly elliptical 'Fenella-isms' (e.g. 'That's where I had chickpeas for the first time in my life. I remember that as clearly as the first time I had sex'), revealing just as much, but no more, than the author wanted to, while providing the reader with the most charming of literary company.

She died from the after effects of a stroke on 11th September 2018, having only recently been awarded, far too belatedly, an OBE 'for services to drama and charity', and been reminded, during her tour to promote her book, of how big and broad and loyal her audience remained, in spite of her spending so much time operating safely underneath the show business radar. She left knowing that she was loved.

She once said, entirely sincerely, 'I wasn't just all larks', and many people appreciated that fact, and many more should now follow suit.

Fenella Fielding was genuinely different: an authentic individual in a culture that felt more comfortable with submissive and pliable stereotypes. Producers knew what to do with those who were willing and able to play the formulaically male-orbiting females: the dumb blondes, the doting wives, the dotty spinsters, the misguided mistresses and the barking battle-axes. They never quite knew what to do with, or how to write for, a strong, independent and unpredictable woman like Fenella Fielding.

Perhaps, while they always claimed not to mind the smoke, deep down they feared the fire.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more