Dennis Main Wilson: The maverick

Sir Huw Wheldon, in his valedictory speech as Managing Director of BBC TV in 1975, warned his younger colleagues: 'Beware of the Grey Men'. His hope was that future broadcasters would be strong enough and committed enough to resist being made to conform according to whatever fear or fashion was currently constraining independent thought and discouraging creative ambition. As far as icons of such an irreverent spirit are concerned, aside from Wheldon himself, there is surely none more inspirational than Dennis Main Wilson.

This is the man who brought different, difficult and dangerous comic talents and shows to the radio - such as Spike Milligan and The Goon Show - and to television - such as Johnny Speight and Till Death Us Do Part. This is the man who stood up for the unusual, the imaginative and the eccentric. This is the man who defended his artists and defied his bosses. This is the man who, many years before Peter Finch's embattled character in Network, was always on the verge of exclaiming: 'I'm mad as hell, and I'm not going to take this anymore!'

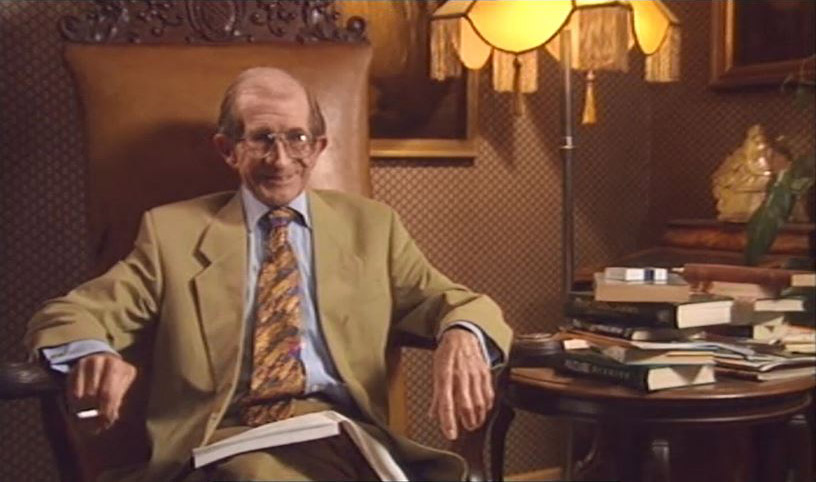

He did not look much like a fighter - he was skinny and rather short, with big eyes made to seem even bigger by the thickness of his spectacle lenses, large protruding ears like slanting jug handles and fingers stained so yellow by nicotine that, rather aptly, they looked like they'd been dabbling in gold dust, and, in later years, he somewhat resembled a tortoise that had been squeezed out of its shell - but he was ferocious when he felt that it really mattered. 'I like to start things,' he once said. 'I like to start programmes. I like to start arguments with management. In my experience, the two usually go together.'

The Main Wilson Way sometimes ran along similar lines to the BBC Way, but, on those occasions when it deviated quite dramatically, no one was sure they were safe. 'I have on two occasions,' he would reflect in later years, 'actually bashed an actor round a rehearsal room. This was towards the end of a series when we were all very tired. A very big star. With megalomania. He had to be sorted out. I see nothing wrong with it. At the end it was all love and friendship.'

There were one or two better all-round producers than him, and better all-round directors - he could soon get bored and be overly casual or erratic in his approach, sometimes a little careless or clumsy, and he was certainly not a great polisher of programmes - but there was no better, or more passionate, enthusiast than Dennis Main Wilson. If he saw a promising performer or writer, or heard of an interesting idea, no one else would prove a greater supporter of their cause.

There are a number of things that made Dennis Main Wilson such an indomitably individualistic programme-maker. One was that, if he saw potential in someone, he would fight for their chance to flourish no matter what anyone else might have thought.

Another was his conviction that, if a project was good enough and important enough, then nothing should stand in his way as he sought to bring it to the broadest possible public. He was also more than ready to bend or break any rule if he felt that doing so would benefit the progression of a programme.

He was a maverick who worked in the mainstream, and, as a consequence, just about everything that he did was memorably eventful.

To understand Main Wilson's broadcasting career, however, one needs to understand Main Wilson's pre-broadcasting career. No one else was so driven by the experiences of a time from before the life lived in the studio.

Born Dennis Geoffrey William Wilson (the other family name of 'Main' would be added at a later date) on 1st May 1924 on an old co-op housing estate in East Dulwich, London, he was a working class grammar school boy with a love of sport (excelling at athletics, rugby, cricket and football) and a knack for learning languages (quickly becoming fluent in German, French and Spanish). Always interested in broadcasting, he left school at seventeen and, sounding upper class ('My school [Colfe's] had taught me to say "hice" instead of "'ouse"') and being multi-lingual, got accepted by the BBC's European Service at Bush House in London.

He was given the job of a recorded programmes assistant, working under Lindley Fraser (an eminent political economist), Alan Bullock (a distinguished historian), Richard Crossman (a future Cabinet Minister) and Hugh Carleton Greene (a future Director-General). 'It was,' he would say, 'better than going to any university, working with brains like that.' He was also charged with the task of writing (mainly in Hochdeutsch) satirical anti-Nazi propaganda for dissemination across the continent.

Called up to the Army in 1943, he was trained to drive a tank and work the wireless, then sent to Sandhurst and commissioned in the Armoured Cavalry. The rest of his time in the military was remarkable: he served in a special mobile 'dirty tricks unit' (which necessitated him being coached in the dark arts of killing someone 'swiftly and silently in plimsolls', discreetly blowing up bridges and sowing subversion behind enemy lines); he became the liaison officer and bodyguard of the key strategist General Sir John Tredinnick Crocker; and was among the first British troops ashore at Juno Beach on D-Day.

In 1945, at the end of the war in Europe, he was seconded to the Allied Control Commission for Germany, and resumed his broadcasting career in Hamburg, running radio light entertainment for Nordwestdeutscher Rundfunk (whose controller was now one of his old bosses from Bush House, Hugh Carleton Greene).

His primary task there was to 'de-Nazify' the German radio system. Apart from studying classified documents to identify and remove anyone known to have Nazi connections, he was also handed the formidable challenge of teaching his vetted German staff how to write radio comedy ('Poke fun of the British occupying authorities if you like,' he told them, 'but for God's sake make people LAUGH!').

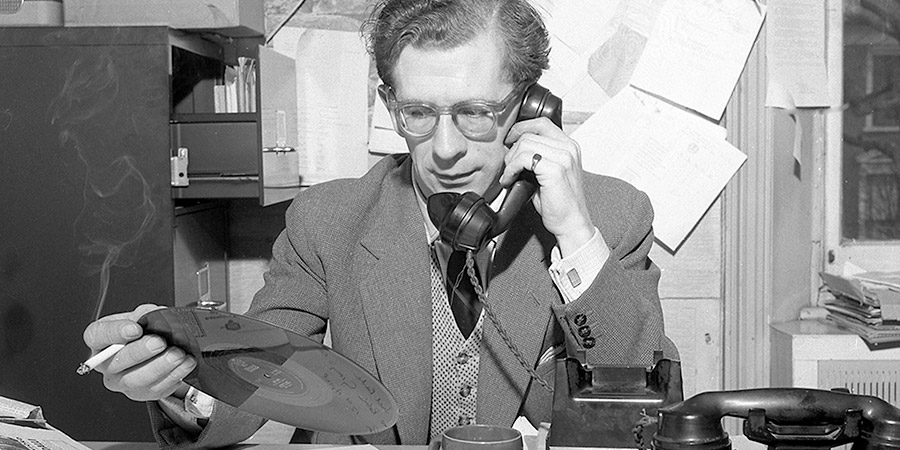

Demobilised eighteen months later in 1947, he joined the BBC once again, this time in the radio variety department. His first job there was to audition all the entertainers returning from military service, which meant that he became the first 'official' broadcasting figure to get to know most of the best young entertainers emerging back into civilian life.

The BBC gave him six months' residency in the downstairs studio of Film House in Wardour Street, where - 'sustained' by crates of Bell's whisky (it was not for nothing that he was nicknamed 'Dennis Main Drain') and endless packs of unfiltered Senior Service cigarettes ('Dennis wandered,' said one wag, 'with his own lonely cloud') - he held auditions every day of each week from ten in the morning until ten at night (seeing in total, according to his own estimate, more than six thousand performers). What he was doing, in effect, was overseeing the recruitment of an entire generation of entertainers, and, as a result, he would become their champion long before any of his colleagues had formed an opinion.

Once these sessions were finally over, he was free to start making programmes as a radio producer, and feature some of the talents that he had spotted. None of his bosses at the BBC, however, had any idea what kind of person they were now letting loose on their variety programmes.

The war had turned Dennis Main Wilson into a crafty kind of social chameleon. He might have acted and sounded appropriately 'posh' and clubbable when in the company of his bosses, but, beneath that reassuringly conservative exterior, he remained strongly working-class in spirit, despising snobbery and elitism and hating The Establishment in general. He had no time for departmental politics, no time for playing games - he wanted to get good things done, and he was quite prepared to fight to do so.

'During the war,' he would later say, 'I saw the most horrendous things happen [and] I saw incredible bravery, and if you lived in that great mish-mash of emotion and danger - incredible bravery and suffering - you're not going to be put upon by some berk up on the 6th floor of the BBC who has got no balls to do something worthwhile.'

In retrospect, therefore, there was a sense of inevitability about Main Wilson's first major project: The Goon Show. Indeed, it seems unlikely that such a programme, in that era, would ever have reached the air, and stayed there, without someone like Main Wilson to push it through.

The writer Barry Took once said, very perceptively, of Dennis Main Wilson that his greatest strength was also his greatest weakness: namely, he empathised so well. His ability to empathise was a strength in the sense that it enabled him to appreciate what an artist was trying to achieve, and believe in it almost as passionately as they did as he worked with them to realise the ideal on the air. The same ability was a weakness in the sense that, to the extent that the artist became increasingly difficult, unpredictable and impractical, so, too, did he - even when the production was teetering on the edge of anarchy.

This would certainly become thrillingly, as well as painfully, evident when Main Wilson worked with Spike Milligan. Socialising together in the pub night after night, they soon realised that they were kindred spirits: sick of war, regimentation and rules, and desperate for freedom, experimentation and fun. When, therefore, Milligan, in 1951, came up with the idea for a new show that epitomised that disposition, Main Wilson made it his mission to bring it to life. 'I was the one,' he would say, 'who bashed the BBC until they let us do it.'

He actually only managed to get a pilot edition commissioned after a more senior producer, Pat Dixon, became involved, but, once it had been recorded, Dixon (somewhat shaken by the chaos that had ensued) sent a memo to the bosses saying that he had no wish to do a series and Main Wilson should be made sole producer. The series - initially called Crazy People - thus went ahead with Main Wilson at the helm, and it proved just as odd, inventive and irreverent as many had hoped or feared.

A second series, broadcast in 1952, was, if anything, even more wild and unpredictable, mainly because its producer was having far too much fun to intervene and impose at least a modicum of order to the proceedings. That, as far as his superiors were concerned, was the problem with Main Wilson's management of the programme: he had effectively 'gone native' and allowed the whole show to become a kind of private joke.

He had also, it was felt, ignored the fact that it was his responsibility to maintain some kind of quality control. Milligan, under Main Wilson's indulgent patronage, was pushing against an open door, and as he was pushing against an open door he was all too often falling down flat on his face. In order to make the most of the comic sorcery that Main Wilson had gleefully released, therefore, someone else was needed to step in and start pushing Milligan to come up with sharper and more structured scripts.

The consequence was that Main Wilson was relieved of his duties and replaced by the far more sober, steady and conventional Peter Eton. It did not really surprise him - he had himself been frustrated and even rather embarrassed by the shambles some episodes had sounded ('I was in the wrong. I was as mad as The Goons. What The Goons needed was someone with a bullwhip') - and he would learn just enough from the experience so as not to leave himself ever again quite so hopelessly exposed.

He certainly improved as a producer during his next major project, which saw him mentor the two young writers Ray Galton and Alan Simpson, along with the comedian Tony Hancock, when they combined to make Hancock's Half Hour. This time, he would still be exceptionally supportive of the talent, but he would also be ready and willing, when he felt it was needed, to criticise and coax better performances from all concerned.

The result was a show, beginning in 1954, that got better and better until it became a social and cultural phenomenon. Thanks to Main Wilson, the writing improved, the characters improved, the acting improved and the stories improved.

Significantly, Main Wilson had matured as a manager, proving himself much more adept at dealing with sudden production problems. One of the most dramatic of these concerned the time in 1955 when Hancock went missing from Hancock's Half Hour.

It happened just days before the date of the first recording for the second series. Hancock had been locked into a long and gruelling run in The Talk Of The Town at the Adelphi Theatre, and, slowly but surely, had worked and worried himself close to an emotional and physical breakdown. One night, instead of completing his performance and then going off for a meal before bed, he walked out on to the London streets and just disappeared. When Main Wilson, as usual, arrived armed with the first script of the new series, the old stage-door keeper told him: 'If you're looking for the boy, sir, 'e's gone'.

The puzzled producer, knowing his star's predilection for drowning his sorrows in drink, searched all of the usual West End pubs and clubs in vain, but was woken in the early hours of the following morning by a telephone call from an old friend of his who was now a Chief Superintendent of Special Branch at Scotland Yard: Hancock, he was informed, had been spotted at the airport boarding the last plane bound for Rome.

Another report came a few hours later: upon arriving in the city, the comedian had booked into a local hotel and then driven south in a hired car to rest and recuperate at the village of Positano on the Neapolitan Riviera. Back in Britain, Main Wilson was left to come to terms with the fact that, when the first episode of the new series of Hancock's Half Hour was recorded, H-H-H-Hancock was going to be A-A-A-Absent. Had this been the more reckless Main Wilson of a couple of years before, he might have hopped on a plane and joined the missing star, but by now he was paying far more attention to his production compass.

Unable to postpone the series until Hancock felt able and willing to return, he discussed the matter with Galton and Simpson and then, with the clock ticking loudly, secured the services of a last-minute replacement: his old Goon Show colleague Harry Secombe. The series thus started on time, with the incongruous-sounding introduction: 'We present Hancock's Half Hour, starring Harry Secombe...'

In this and the next two hastily re-written episodes, the uncomplaining Secombe helped hold the action, and series, together. Hancock finally returned to the country mid-way through the first week in May ('like a little dog,' Main Wilson would say, 'with his tail between his legs') - just in time to appear in the fourth half-hour of his own series. The crisis was over, and Main Wilson had proven to himself, as well as to his bosses, that he could take a step back when required and rescue his friends, and his programme, from danger.

It was this feeling of greater maturity, along with the extraordinary success of the show, which made Main Wilson start believing that he was ready to work in television. Whether television was ready for Main Wilson, however, was another matter entirely.

He made the move in 1957 (he would have done so two years earlier had it not been for the fact that, unbeknownst to him, his radio boss, Pat Hillyard, had been so keen to hold on to him that he'd been intercepting all of his applications and tearing them up on the spot). There followed a period where his talents were tested on such diverse formats as the popular music show Six-Five Special (hating the then-fashionable skiffle, he tried smuggling some jazz into it) and the panel show What's My Line? (he respected its success but personally found it desperately dull) until he was allowed to concentrate on comedy.

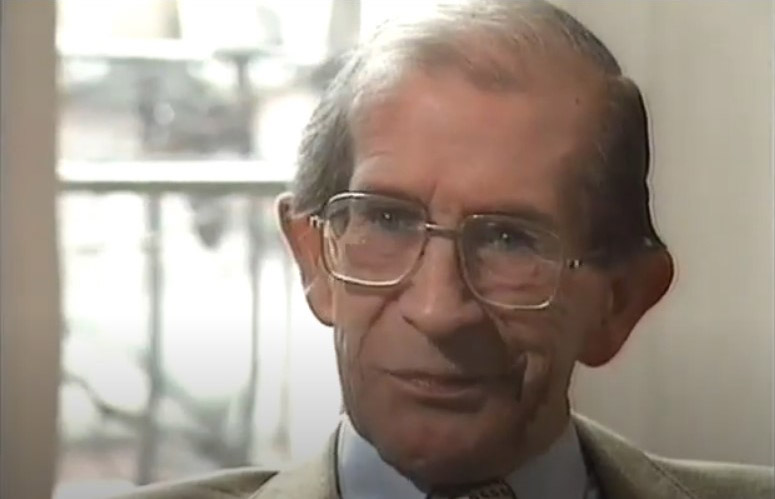

This was when Main Wilson benefitted from the most propitious of coincidences. Just when he was ready to start challenging expectations and taking big risks with BBC comedy, his old friend and colleague Hugh Carleton Greene (pictured) became (in 1960) the BBC's new Director-General.

It was perfect timing: the maverick was now being managed by a man who actually liked mavericks. Greene, like Main Wilson, had been through a hard war, and witnessed the intolerance and brutality of Nazism at first hand, and it had left him determined to celebrate diversity and liberty and tolerance in everything that the BBC did. Under any other boss, Main Wilson might well have been distracted by so many battles that he would have ended up being driven out; under Greene, however, he was able to thrive.

He would further protect himself, from interference lower down in the hierarchy, by resorting occasionally to a couple of crafty strategies: rogue publicity and attritional loquacity.

He cultivated a network of friends in the press, to whom he would leak stories of forthcoming decisions, favouring himself and his plans, before the decisions had actually been made - knowing that his bosses would probably rather go along with it all rather than be seen to be 'backtracking'. He also discouraged executives from asking too many questions of him by making any answer far too long and elaborate for most of them to endure (an in-joke at the time was that a simple inquiry as to what Main Wilson had thought of last week's radio output would almost certainly prompt him to begin, 'Well, to answer that, one must first go back to Bologna, in the late-1870s, and Marconi's experiences as a boy...').

Having an ally right at the top of the BBC, however, would be the making of him in this medium. Greene was the first great enemy of the Grey Men, and he was counting on people like Main Wilson to bring some colour to the Corporation.

It also helped that Main Wilson's immediate superior was the similarly liberal Eric Maschwitz, who was Head of Light Entertainment at the time and no stranger himself to a little harmless mischief. Amused by his young producer's sometimes overly secretive way of working, he gave him the affectionate nickname of 'Dr Sinister' and largely left him to his own devices.

Main Wilson's first major innovation, in such a progressive creative climate, was to set up a sitcom that not only dealt with industrial conflict but was also full of strong roles for strong women: The Rag Trade (pictured, 1961-63). Written by the two Ronnies, Chesney and Wolfe, it featured a basic workers-versus-management situation, but, aside from Peter Jones as the boss and Reg Varney as the foreman, the show was driven mainly by the likes of Miriam Karlin (as the militant shop steward), Sheila Hancock, Barbara Windsor, Esme Cannon, Ann Beach and Wanda Ventham. Massively successful, it helped Main Wilson make his mark.

His biggest hit, however, and his biggest controversy, was yet to come. In 1965, the left-wing writer Johnny Speight came to him with a script for the pilot of a new comedy, featuring an ignorant, loud-mouthed working-class bigot, called Till Death Us Do Part. The 'anti-sitcom' of its time, with its unsympathetic characters, its unhappy family context and its angry arguments about such divisive contemporary topics as the Monarchy, party politics, race relations and immigration, sex and sexism, censorship, social mobility and sport, it was just the kind of show for which Main Wilson had been looking.

Eric Maschwitz, by this time, had departed, and his replacement was the far more conventional, and cautious, executive Tom Sloan, but Main Wilson, employing all of his tried and tested tricks of persuasion and evasion, still managed to smuggle the project through to the screen. When it was first broadcast as a pilot episode, the producer would recall, he and Speight could hardly contain their shared sense of excitement:

Johnny and I went drinking in the White Elephant in Curzon Street that night. All our friends had seen it and hooray: champagne! And in the Elephant you get next morning's papers round about half past eleven in the evening. The crits were super, so we decided not to leave the Elephant, and we stayed there and drank champagne all night and then had breakfast. Turned up at the BBC Club bar at lunchtime, still on champagne, and all our friends came up and said: 'Wow, follow that!' [They said] it was aggressive - within the first three pages we'd destroyed Harold Wilson, we'd destroyed Ted Heath, anybody in charge in Britain. [...] It was a total breath of total fresh air. It had never been done before and it was flat out. [...] And the audience didn't know what had hit them.

So we are back [the following week] - it's now lunchtime-ish - in the BBC Club bar, on a Wednesday. And Wednesday is [the day of the weekly] programme board meeting, to review last week's output by all the bosses of BBC Television. And our mates were buying us drinks, and in came Tom Sloan, who was the head of my department - entertainment. Johnny Speight, who had this stutter, bless him, [...] went up to Tom and he said: 'W-w-w-what about that for a bloody series, mate, eh?' Tom froze and actually said: 'Over our corporate dead body do we make a series out of subversive muck like that!' And my heart sank. Luckily, down from the same board meeting came the Controller of BBC One, Michael Peacock, and the Controller of BBC Two, David Attenborough. And David giggled and nudged Peacock and said: 'If you don't want it on One, I'll have it on BBC Two!'

Peacock promptly commissioned a series for BBC One, Sloan cooled down and wished it luck, and Till Death Us Do Part was guaranteed a future. An ecstatic Main Wilson was convinced that he and his team were now set to make something truly extraordinary: 'I'd started with The Goon Show, I'd done Hancock's Half Hour, I'd done the first all-girls' show, The Rag Trade. I'd done some wild shows, all experimental so far, and this was going to be the big one.'

When, therefore, he bumped into Frank Muir (the BBC's then Head of Comedy) a few weeks later - once again in the bar (which often seemed like his second office) at Television Centre - he could hardly contain himself as he revealed his plans for a ground-breaking, Orson Welles-style opening sequence that, he announced with bright and widened eyes, was going to be shot from high above London in a helicopter. Muir - who considered Main Wilson to be 'twenty per cent near-genius and eighty per cent over-enthusiastic' - put down his glass of white wine, raised his eyebrows and reminded Main Wilson that he had already exceeded his budget for the entire run and the actual series had not even started.

'Bugger the budget!' barked the producer, who protested that it would only cost the Corporation an extra four hundred pounds to realise this brilliant little dream. Muir smiled weakly but sympathetically: he rather liked the idea, and he admired Main Wilson, so he said that they could go ahead with the shot.

The conversation, however, did not end there. 'I'm afraid there's a problem,' said Main Wilson, who was now blushing slightly and glancing down nervously at his feet. 'The four hundred pounds only stretches to a single-rotor chopper,' he mumbled, 'and in that we are only allowed to fly over the Thames - that is, over water. To fly over land we have to have a twin-rotor job.'

Muir tried hard not to gasp: 'And how much would that cost?' Main Wilson shuffled awkwardly and said, 'The twin-rotor chopper comes in at eight hundred and fifty pounds per hour.' Muir thought to himself for a moment, wondering where any spare funds might be found, sighed deeply and then said: 'Go ahead with your shot.'

Main Wilson shook his hand vigorously, patted his arm and started smiling: 'Thanks so much. I knew I could count on your support.' Then he paused, threw Muir a shy look, took a quick breath and added: 'The fact is I did the shot last Thursday. It didn't work.'

The following week, therefore, Main Wilson and Speight went back up in the helicopter:

We did a flight over Wapping in a chopper. [We were] looking for an area which would encompass all the location sequences - the area as we were going to describe. And it had to have a bit of a playing field, a pub round the corner, a church not too far away. It had got to be near the docks, got to be near the river. It had to be in Wapping High Street if at all possible. So we did all of that. And we then persuaded them to let us go back to opposite Big Ben, and I said to the pilot: 'When I say "go," split us from opposite Big Ben to the end of Wapping High Street, where it becomes a dog leg and becomes Garnett Street, where the cement Silo is'. He got that and we did it in one minute and twenty-three seconds - which is brilliant because it's one minute forty-three for Big Ben to strike the hour and chime eleven, and that was the opening titles.

The tireless producer, however, was still not quite finished yet. While Speight thought long and hard about each one of his characters, Main Wilson fussed over every aspect of the set:

I called in my set designer to discuss what kind of house they lived in. And it was to be a twelve foot square front room with a scullery out the back, with an earthenware sink, a bath in the scullery with a lid on where you keep all the crockery, a copper where you heat up all the hot water to hand-bail the water into the bath and run the cold tap, and a bog out the back, and a tiny garden, and a front door that opened into a hall and the stairs go straight up and you turn left into the front room. In the front room there's got to be a two-seater settee, two armchairs, a piano, a dining table, four chairs and a sideboard, in a twelve foot square room. That [would become] our trademark; that was it. That in fact was the exact floor plan and the furniture arrangement of my Mum and Dad's house, and they never spotted it. And they thought the Garnett family lived in the most dreadful circumstances!

Proving that there were no hard feelings since the incident with the helicopter (as well as demonstrating how supportive BBC executives could be during this era), Frank Muir would make a point of praising all of Dennis Main Wilson's prodigious efforts during this period, declaring that it 'was almost impossible to overstate [his] contribution': 'Dennis did nothing by halves. In the early days he almost lived with Johnny Speight to help get the Till Death scripts out on time, and even wrestled Johnny out of Annabel's nightclub in Berkeley Square in the early hours of one morning to make sure that there would be a script for rehearsal later that day.'

The series, which began in June 1966, would run for almost ten years, watched by as many as twenty million people each week, and - much to Main Wilson's huge delight - would provoke near-constant criticism from diverse directions. 'Our intention,' he would later reflect, 'had been to put Alf Garnett on show and say to the British nation "This, for better or for worse, is you - there is something of this guy in all of you, and don't pretend there isn't, be you working class, middle or upper class, an MP, whatever. Everybody is an Alf Garnett". And we did it for seven series.'

Main Wilson, however, was the last one to rest on his laurels. He simply never tired of finding and fostering new talent and accepting other battles to fight.

It was him, for example, who spotted the potential of Dick Clement and Ian La Frenais and pulled the right strings to get The Likely Lads (pictured) on the air. It was him who nurtured Marty Feldman not only as a writer but also as a performer, overseeing his rise to stardom. It was him who managed to get the [o[]BBC[/o] to give Barry Humphries his first major TV show. It was him whom a humble BBC scene shifter named John Sullivan sought out ('I've heard you're the chap who is willing to give unknowns a chance') to discuss his plans for writing a sitcom called Citizen Smith (which Main Wilson made sure got made).

It was also him who gave Clive Anderson and Griff Rhys Jones their first chance on TV when he televised their Cambridge Footlights revue in 1974, and it was him who did the same for Emma Thompson, Stephen Fry, Hugh Laurie and Tony Slattery in 1982 (pictured). Right up to his retirement in the mid-Eighties, he kept on looking, listening, believing and encouraging.

He also never stopped himself when he felt that criticisms were required. Some of the more self-indulgent of young sketch writers tended to frustrate him. 'They do the joke on page 3 and go on until page 94,' he complained. 'It's their bad luck that they have never had to go out and work to an audience.'

He was much more irritated by 'busy' comedy directors whose basic insecurity caused them to show-off their own skills rather than those of the performers. 'The director's job on television in general, but in television comedy in particular, is solely to make sure that what is happening in front of the camera is an entertainment,' he insisted. 'Stick Frankie Howerd in front of a camera for twelve minutes and he will stop the show four times without a camera-cut anywhere. If direction is noticeable it is bad direction. The camera is an ancillary thing. Is the show funny or not is the only thing that matters.'

He never, however, carped for carping's sake. While he could see straight through those who sought to use 'modernity' as a specious means to resist learning any lessons at all from the past, he stayed a staunch supporter of the genuinely innovative, the daringly different and the fiercely idealistic.

If you were a fake he was your enemy. If you were a proper talent, no matter how raw or flawed, he was your friend.

Some executives had never stopped thinking of him as a troublesome non-conformist ('Oh, Dennis, oh dear, he was all over the shop,' one of them said to me, shaking his head at the memory. 'Oh, God, yes. ALL OVER THE SHOP!'), but most of them, over the years, had come to appreciate his special contribution, and, more importantly, all of the comic performers with whom he worked would love him for all that he had done for them.

When Dennis Main Wilson died, aged seventy-two, in 1997, the industry was fuller than ever of Wheldon's dreaded Grey Men, which caused creative people to feel his loss even more deeply and keenly. He was one of those who dared to dream, and dared others to dream, and was passionate about producing things that provoked surprise, pleasure and pride on both sides of the screen.

The best way to honour his memory, therefore, is to continue to be inspired by his individualism, and his big, messy, noisy enthusiasms, and stay true to his own insistent dictum: 'If you believe in something, then stick your bloody neck out and go for it!'

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more