This Town Ain't Big Enough For The Both Of Us: Comedy Rivalries

We all know about the comedians who worked together and eventually fell out; close relationships can crumble like that. What is rather more peculiar are the comedians who never really worked with each other but still ended up falling out; they are the ones who cut out the friendship and went straight for the festering resentment.

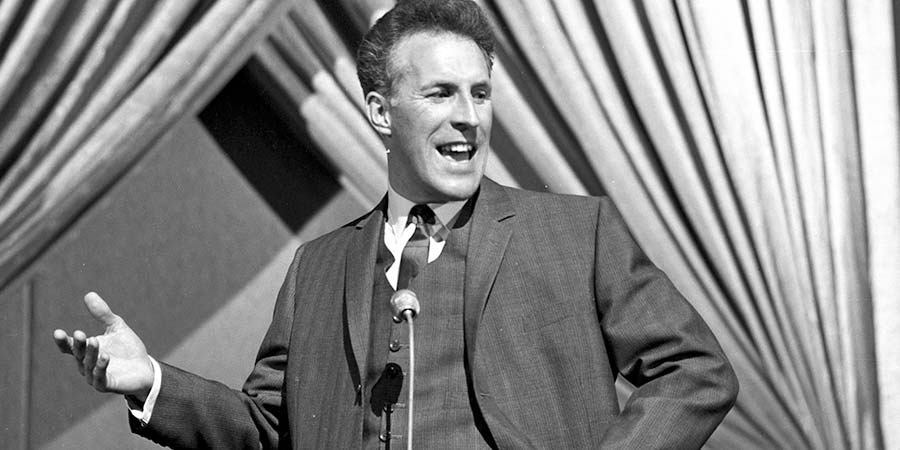

There are two such non-relationships that, in the history of British comedy, are particularly fascinating for the fierceness of their antipathy. One concerns Tommy Trinder (pictured below) and Bruce Forsyth, and the other is about Frankie Howerd and Larry Grayson. What drove these rivalries on was the conviction of one comedian that the other one was threatening to erase them by ripping off their own act.

The rivalry between Trinder and Forsyth, indeed, came to seem like a bitter sci-fi-style clash of the clones, with each one intent on annihilating the other to take sole ownership of the one identity. There were simply so many things that these two men had in common that, eventually, there only seemed room enough for one of them in the show business world.

Both men, for instance, came from London- Trinder from the south of the city, in Streatham, and Forsyth from the north, in Edmonton. Both men came from similar family backgrounds - Trinder's father was a tram conductor, Forsyth's a car mechanic. Both men were driven to perform and entertain from an early age - Trinder making his stage debut at the age of twelve, Forsyth at fourteen. Both men toured in their teens in revue, with both of them combining comedy with singing and dancing. Both men taught themselves how to win over tough audiences in difficult conditions - Trinder during the war in bomb-battered venues and Forsyth just after the war at the Windmill - and both men made their mark on television during the 1950s.

They also, of course, looked and acted remarkably similar. Both of them were tall and whippet thin, both had broad grins and famously protruding chins, both made a point of associating themselves with catchphrases (Trinder's was 'You lucky people!' and Forsyth's was 'I'm in charge!'), both had a special gift for ad-libbing and both were sharp-elbowed, loud-voiced, swift-talking southern stand-ups who looked to dominate whatever company they were in.

Trinder, as the older of the two by some nineteen years, simply got to be famous first. Hailed by some (including himself) as one of the entertainers 'who kept Britain laughing' during the war, he had been a regular at the London Palladium since the early 1940s, topped the bill in numerous West End revues, appeared in several home-grown movies and enjoyed some hugely successful tours of Australia and South Africa.

Combining the skin of a rhino with the gift of the gab (once, when he opened his act at Mayfair's then-fashionable Embassy Club with his usual fog-horned self-introduction of 'Trinder's the name,' a glum Orson Welles, having earlier that day been divorced from Rita Hayworth, growled back, 'Well, change it,' to which Trinder retorted brightly: 'Is that an offer of marriage?'), he had emerged from wartime as by far the most confident operator in the often unpredictable context of live television, able to cope with everything from audience heckles to technical troubles.

It therefore came as no surprise when, in 1955, Trinder became the first host of Sunday Night At The London Palladium, ITV's new flagship entertainment show, which would go on to become one of the longest-running and most successful television variety series in the history of British TV. Playing regularly to an estimated twelve million viewers, the programme quickly cemented Trinder's status as one of the country's biggest stars, as well as (thanks to his bulging property portfolio) probably the wealthiest.

He had everything. Having everything, however, is traditionally when comics start worrying about losing everything. They begin looking around for possible rivals, potential usurpers, and, in Trinder's case, that caused him, after a couple of years as 'Mr Sunday Night,' to begin looking at, among other up-and-coming performers, Bruce Forsyth.

Trinder had been aware of Forsyth for some time. The young comedian had kept sliding into sight, like a shark fin surfacing in the sea, with increasingly frequent regularity during recent months. One could almost hear the ominous stabbing cello sounds growing louder and louder as one long-jawed performer watched the other long-jawed performer come closer and closer.

They were finally set to meet when Forsyth was booked to appear, on 17th November 1957, as a guest on Trinder's show - which, on this particular occasion, was taking place at the Prince of Wales Theatre rather than the Palladium (because the latter was being used for rehearsals for the forthcoming Royal Variety Performance). The news of this had plunged Trinder into a neurotic state of mind, because he already suspected that his own position was becoming increasingly insecure.

A classic loose cannon, he had fired off far too many broadsides, and upset far too many people (the popular singer and dancer Pat Kirkwood, one of his old co-stars, had called him 'rude and insulting and downright nasty,' and many others agreed). He had offended the managing director of ATV, Val Parnell, on multiple occasions, as well as Parnell's deputy, Lew Grade, and he had already rattled his newly-installed producer, Brian Tesler, too. He had also upset countless colleagues and competitors with his arrogance and abrasiveness, and he knew that plenty of enemies had been made.

Nothing had been said so far about his long-term future, in terms of new contract discussions, but he had started to speculate as to what machinations might be going on behind the scenes. He was feeling decidedly edgy. When, therefore, this younger and more energetic-looking version of himself was signed up for an appearance on the show, he started to think, and worry, and plot.

Forsyth was blissfully unaware of what was about to happen. He was simply delighted, after years of slogging his way around the provincial circuits, to have made the breakthrough and won a spot on such a major mainstream TV show. Before he could even reach the microphone, however, it suddenly became clear to him that Tommy Trinder was out to ruin his big moment.

The stage convention is that one leaves the stage on the same side as one entered it. In this case, Trinder was due to exit on the left and Forsyth was set to enter from the right. Trinder, however, had other ideas.

As he was introducing his guest, Forsyth started to walk on from the right-hand side, expecting Trinder to turn and walk off to the left. Instead, Trinder, with a fixed shark-like grin and a menacing cold-eyed stare, marched off to the right, straight at Forsyth, as if on a collision course.

The younger comedian, as Trinder had intended, was startled. This was live television and here was probably the best-known and most powerful host in the country deliberately trying to make him look foolish.

'I was left with no alternative but to react spontaneously,' Forsyth would later recall. 'I grabbed hold of him, looked him straight in the eye, spun him round, went to centre stage, looked towards where Tommy had gone, and said to the audience, "Oooo, hasn't he got a big chin?" This got me a good laugh from the audience, who probably thought it was part of the act. But it was not.'

It was, symbolically, the first knockdown of the title fight. Trinder was now stuck in the wings, seething, as he listened to the young pretender bask in the laughs.

In the days and weeks and months that followed, Trinder would do all that he could behind the scenes to hinder the progress of this dangerous comic doppelgänger. He briefed all of the friendly journalists he knew about Forsyth's supposed 'borrowings' from his own act and material, discouraged producers from trusting such a 'raw' and 'limited' talent, and gossiped to other performers about how ruthlessly ambitious he was. Forsyth, in turn, did not hesitate to let as many people as he could know just how unprofessional and unfair Trinder had been, and how other up-and-coming comics should protect themselves from him in future. The blows, from both sides, were now coming in low and hard.

This bitter battle came to an end one year later, in 1958, when Tommy Trinder was fired from Sunday Night At The London Palladium, but it was his fault, not Forsyth's. It was down to that long-standing double act of Tommy Trinder and hubris.

Trinder was one of the first stars of Britain's television age to believe in his own hype and abuse the trust that his masters bestowed. He had gradually moved on from mocking some of his own guests and the standard of his own show, to complaining on air about the overall quality of the channel that employed him.

So long as his barbs got laughs he simply didn't care what targets he attacked. His bosses, however, had a different opinion.

They had long disliked his abrasive nature and startling lack of respect, and, as they were now looking to take their variety output a little 'upmarket', they were wincing more and more at his earthy, old-fashioned, salty style of humour. As usual, however, popularity mattered more than principles in commercial television, and so they had tolerated him while his appeal still seemed strong.

Now, however, they smelt the first few drops of blood. Some of the tabloid critics had started to tire of Trinder - there were several disparaging remarks about his 'stale material' and 'laboured clowning', and one reviewer had complained that, while Trinder still metaphorically 'used a cudgel or a piece of lead piping' to elicit some laughs, the success of other hosts who used subtler means 'has proved that people who watch variety shows are often intelligent people'. It was just what the executives at ATV had wanted to hear. Now, they knew, they could act.

A myth has grown up over the years (encouraged in part by the man himself) that Trinder was sacked 'at a minute's notice' for some dramatic misdemeanour, possibly involving an insult aimed at Bernard Delfont and/or Lew Grade (above). That is not, in truth, how it happened.

When Trinder finished the second series of Sunday Night, in the summer of 1957, it was made clear enough to him that the new producer, Brian Tesler, was looking to 'shake things up a bit', and there could be no guarantees as to his long-term future as resident compère. This - as expected - was quite enough to provoke Trinder into a bitter rage about the ingratitude and disloyalty of his employers, and, in a bid to keep some control over his own career, he promptly arranged a lucrative concert tour of South Africa - where he was still hugely popular - for the autumn. It was then announced that the next series of Sunday Night would begin in his absence with a number of guest presenters, and then Trinder would return to host the final few episodes.

This is what actually happened. Trinder was back for the second half of the series, concluding the run on 11th May 1958. There was no high profile announcement that he had taken his final bow, but neither was there some sudden sacking. Both parties had known, for months, that the parting of ways was coming. Trinder simply moved on to star in a summer season, and the producers prepared to move the show on without him.

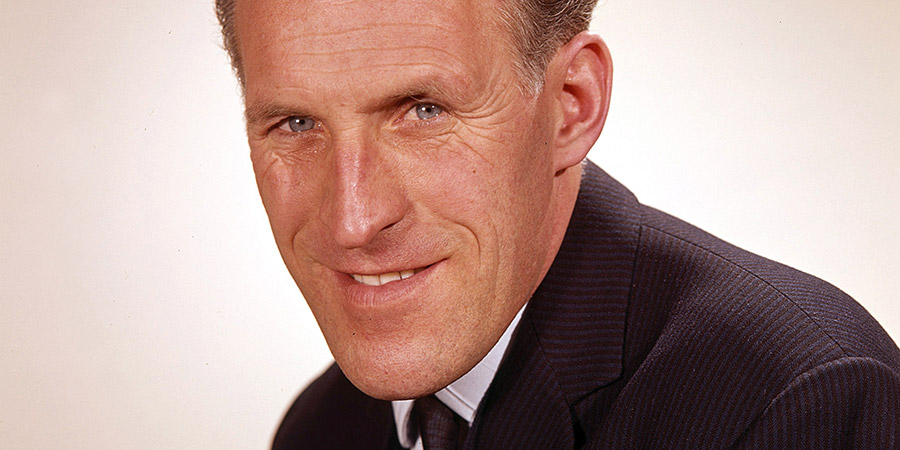

Parnell and Tesler could now turn to selecting his successor, and it did not take them long to fasten on Bruce Forsyth as the right man for the job. He had only just turned thirty, was fresh and funny and full of energy, he shared Trinder's common touch but also had a certain flair that suited perfectly his producer's plans for a more polished and sophisticated sort of show.

The news was thus announced, in a very low-key manner, on 28th August 1958: Bruce Forsyth had been awarded 'one of TV's plum jobs' - Sunday Night At The London Palladium. When the show returned in the autumn, he would be the new permanent host.

Tommy Trinder, upon hearing the news, was convinced - quite erroneously - that the producers had picked Forsyth as his successor long before he had actually left the show, and he was also convinced - again erroneously - that the younger man had been actively campaigning behind the scenes to achieve that end. From that moment on, therefore, Tommy Trinder would despise Bruce Forsyth as the man who, in his eyes, had robbed him of his career.

He certainly had nowhere left to go on commercial TV. Trinder had indeed upset Bernard Delfont and other ITV bosses sufficiently in the last couple of years to have ensured that he would not be welcome on the channel for the foreseeable future.

In one incident in particular, when the now-sacked Trinder was hosting the (untelevised) annual Television Producers' Guild awards event, he deviated from the script and suddenly announced: 'And now I've a special word for the award-winners. You think you're lucky people? You think your future on TV is assured? Let me tell you, my friends, as far as I'm concerned these awards don't mean a damn thing!'

He then produced from his jacket pocket a gold cigarette case that Val Parnell had once given him, with the engraved tribute: 'For Tommy Trinder, who has absolutely proved himself on so many occasions to be ATV's outstanding man.' Holding the memento high above his head, he snarled bitterly: 'I know what I'm talking about - I was given this gold cigarette case for compèring Sunday Night At The London Palladium - and the following week I got the sack!'

The fact that he had trimmed the timeline for dramatic effect - the gift had actually been given to him more than a year prior to his departure - only enraged those insiders present (including a scarlet-cheeked Val Parnell) even more. If any ITV executives had still been even slightly sympathetic to Trinder up to this point, they no longer felt anything but anger and resentment towards him by the time that the occasion was over.

In the age of two-channel TV, therefore, Trinder had effectively switched one of them off. He had no choice, therefore, but to seek out and accept whatever other options he could find.

There would be a short-lived variety-style series on the BBC called Trinder's Box (1959), but after that -aside from theatrical work - he was limited to the odd guest appearance on other people's shows, where, increasingly, he seemed like some ghost from an earlier era. As the Sixties went on, growing increasingly youth-conscious, Tommy Trinder, looking lined and tired in his trademark trilby hat, only appeared at home on nostalgia shows like The Good Old Days.

Forsyth, meanwhile, went from strength to strength, quickly eclipsing his old rival to establish himself as Britain's master of live TV entertainment. He was Trinder 2.0, the new and improved model, suited perfectly to a medium that was now getting faster, looser and more daring. Just like his predecessor, he could charm the masses; unlike his predecessor, he could charm his bosses, too. His future was well and truly secure.

The two men did not meet again for several years. No effort was needed to stay apart: Forsyth was starring on TV and in the West End, while Trinder was reduced to touring the provincial theatres. Then, in 1967, their paths finally crossed once again.

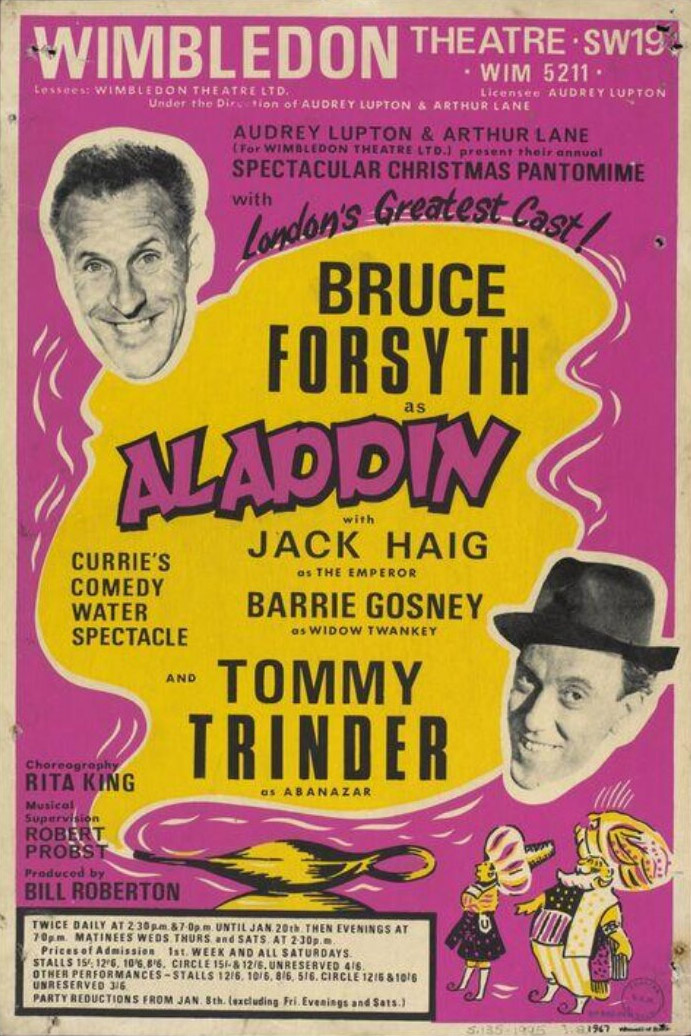

It took Forsyth completely by surprise. He was working one day in the north of England when he decided, on a whim, to telephone his good friend Frankie Howerd to catch up on some chat. Howerd's sister, Betty, answered the call: 'Hello, dear,' she said, before adding brightly, 'By the way: good luck to you in the pantomime at the Wimbledon Theatre!'

Forsyth was bemused. 'What?' he exclaimed. 'Bruce, it's in the Evening Standard,' said Betty. You're there for Aladdin at Christmas.'

If that news was not bad enough - he was not even much of a fan of pantomimes - then what came next would really alarm him. 'Who else is in it?' he asked. 'Tommy Trinder,' she replied.

Forsyth felt as though someone had punched him in the stomach. 'How can I be in a show with HIM?' he groaned.

Once he got back to London, he started to investigate the situation, and discovered, to his horror, that the news was true. His imperious agent, Miff Ferrie, had made the booking without even bothering to consult him.

Forsyth had been fighting with the notoriously uncompromising, ultra-controlling and unnervingly dour Ferrie for some time: they had been dragging each other in and out of the law courts since the early days of the decade. This latest act, for Forsyth, was the last straw.

He agreed to pay Ferrie £20,000, there and then, just to be rid of him once and for all. The pantomime, however, was not something he could wriggle out of so easily, and so he had to find a way to get through it without having to deal with, or speak to, Trinder.

It wasn't just that Forsyth had no desire to spend time with the man who had tried to block his progress. It was also because he still respected the older man enough to fear that, even now, he might be able to embarrass him if they shared the same stage. They were, after all, so similar, with more or less the same set of skills, that each performer would surely feel as though he was trying to outwit himself, like moving to catch out a mirror image. Trinder, still eager for revenge, might have been relishing that challenge, but Forsyth had no appetite for it at all.

'I had a word with the producer,' Forsyth would recall, 'and said I didn't want to be involved in any stage action where I may have to match him for ad-libs. Believe me, Tommy was a great ad-libber.'

The result was that the producer, bowing to the power of the now-bigger star, arranged the action so that at no point would Trinder be on the stage at the same time as Forsyth. The final round of their long-running fight would thus never actually happen.

They went their separate ways, for good, after that. Forsyth soared on to other game shows and quiz shows and stage shows, enjoying massive audiences and winning many awards. Trinder, in contrast, slumped to smaller and smaller venues, and fewer and fewer people who remembered what a big star he once had been.

He could easily have retired, licked his wounds and enjoyed the rest of his life. He had done enough, achieved enough and earned enough to shake off any lingering resentments and enjoy doing other things.

The sad thing was that he remained addicted to performing, long after the demand for him to perform had died away. He played obscure clubs, small corporate events and holiday camps. He even, much to the astonishment of one young comedian who witnessed him there, did some warm-up work for Tyne Tees Television in Newcastle, toiling away trying to amuse a young audience that seemed mystified by the old man in the hat. 'I know what you're thinking,' Trinder told his fellow comic over a drink afterwards. 'But I just want to be part of it still'.

While Bruce Forsyth had scored a knockout in his bout with Tommy Trinder, the clash between his friend, Frankie Howerd, and Larry Grayson (pictured below) would prove a rather more complicated affair. The climax of it would, ironically enough, be caused, unwittingly, by Forsyth himself.

For a long time, there had been no tension at all between Howerd and Grayson (even though, in terms of age, they were contemporaries), simply because they had moved in very different circles. Howerd had been one of the best-known comedians in Britain since the late 1940s, starred in numerous shows on radio and television, and also enjoyed a couple of huge hits in the West End. Grayson, on the other hand, had spent the first thirty years or so of his career toiling away in the relative obscurity of male revues and drag shows.

The two men only started to think of each other as competitors at the start of the 1970s, when Grayson, aided by the expert guidance of his then-agent Michael Grade, finally broke into television, first via a few well-received guest appearances and then with his own popular ITV show, Shut That Door! (1972-4). This was the moment when Frankie Howerd started to be alarmed.

Both men, of course, were closeted gays, and both used a clever brand of camp that managed to mock their own identities, and the prejudices of their audience, in such an engaging and playful way that there was real warmth and affection in the way that they were received. Up until now, however, Frankie Howerd had monopolised this means of charming a large audience; the relatively sudden arrival of Larry Grayson into the same spotlight, therefore, made the more established comedian distinctly uneasy.

He had, after all, struggled even on his own to maintain a career with a style of humour that seemed to keep slipping in and out of fashion. He had been a massive star in the forties, only to slump somewhat in the early fifties; then he rose and fell again; suffered a nervous breakdown; clawed his way back up to the top yet again; then slid down a little yet again; then came back as the star of his own BBC sitcom, Up Pompeii! (1969-70) - and now, just as Grayson's career was taking off, Howerd was sinking down into another period of intense insecurity. Now, he reasoned, there were two of them competing for the same scarce resources.

What made it worse for Howerd was the fact that he was convinced that Grayson was copying his act - an act he had spent decades perfecting. He did, it must be said, have a point.

Howerd, for example, was known for his comic vulnerability, fussiness and hypochondria ('Coh, I've had a terrible week!'); so, now, was Grayson ('Ooh, I've had a funny week!'). He was known for his gossipy, 'over the garden wall', manner of conversing and conspiring with the audience ('Psst - come here: liss-en, liss-en...'); so, now, was Grayson ('Now, this is just between you and me...'). He was known for his mock indignation at his listeners' 'dirty' minds ('What a rude woman!'); so, now, was Grayson ('What a common fellow!'). He was known for his sensitivity to inclement weather ('It's chilly tonight, 'tis, yehsss, it's bitter out!'); so, now, was Grayson ('The draught in here!'). He was known for his constant carping about unseen authority figures - producers, directors, managers - who were forever bossing him about ('The NERVE of the man!'); so, now, was Grayson ('I can't take much more of him!'). He was known for his battles with his hapless pianist sidekick ('No, don't laugh, it might be one of your own!'); so, now, was Grayson ('Come on - you're not embalmed!'). He was known for apologising about his lack of a proper act ('I haven't got much for you this week'); so, now, was Grayson ('I really don't know what to do').

Of course, Frankie Howerd's own craftily camp performance had not emerged from nowhere - if his hero Sid Field had still been around, he would no doubt have recognised elements from his own act (e.g. 'Nay, nay and thrice nay!') - but his first few views of Grayson in the early 1970s must have stunned him with the similarity of the whole persona. Once the shock wore off, however, the resentment started to rise up.

Here was the arch-worrier Howerd, sitting disconsolately at home, terrified that he was once again in danger of being phased out of his profession, watching someone on TV basically being, well, him. It grated even more that Grayson was not just being 'him,' but also being a slightly more outrageous version of him - more obviously camp, with more knowing winks and nudges woven into the material - and the broad national audience was still embracing him.

That, to a man who had been obliged to fight to protect his popularity and sometimes even save his career during a time when homosexuality was still illegal, blackmail threats and beatings were rife and many bosses in the business were aggressively homophobic, really rankled. It felt like he had run most of a one-man marathon, only to discover that it had now turned into a relay race, and someone else, with fresher legs, was running off with the baton.

Sure enough, as Howerd struggled for decent new projects to pursue, Grayson seemed to have one excellent offer after another land right in his lap. After Shut That Door! ended he hosted his own prime time special, The Larry Grayson Hour Of Stars (1974), before going straight into a new starring vehicle, The Larry Grayson Show (1975-77), and he was also popping up on panel shows, chat shows and variety specials, embarking on lucrative theatre tours, releasing novelty singles and starring in high profile pantomimes.

Howerd, meanwhile, had to make do with one series of Whoops Baghdad (1973) - an uninspired and generally poorly-received 'sequel' to Up Pompeii!. By the middle of the decade, feeling unwanted and unappreciated by British television, he was having to resort to finding work abroad, making one sitcom in Canada (The Frankie Howerd Show, 1976) and another in Australia (Up The Convicts, also 1976).

By this stage, it was becoming painfully clear to his friends and old colleagues how embittered he was about Larry Grayson. Barry Cryer, for example, was having dinner with him one evening at a restaurant near the comedian's Kensington home when, quite innocently, he asked: 'Frank, what do you think about Larry Grayson?'

Howerd's eyes widened and then narrowed, his cheeks reddened, and then he banged his fist on the table and snarled, 'That man stole my bread and butter!' It was quite an ear-catching thing to shout out in a restaurant, but, oblivious to all of the attention, he then raged on and on about the damage Grayson's 'plagiarism' had done to his own career. Cryer sat there, as if in front of a vintage hair dryer, nodding in sympathy as the hot air blasted at him. He would not be the last person to wish that he had never asked.

Howerd was not, in fact, the only camp comedian moaning about Larry Grayson. Kenneth Williams was also busy scribbling barbed remarks about him in his diary: 'Of course! They've found other people to do [the act], and cheaper people in every sense.'

Williams, however, had little to really complain about, because he and Grayson were actually very different performers, suited to different formats. Howerd's anger, on the other hand, was far more justified, and it was about to reach an intensity that was positively volcanic.

The catalyst would be, of all things, Bruce Forsyth's decision in 1977 to leave his role as host of The Generation Game. The show was one of the highlights of the BBC's Saturday night schedule, regularly attracting audiences of about twenty-one million, and it had elevated Forsyth to even greater fame than before. Bill Cotton, the BBC's then Head of Light Entertainment, was determined to find a replacement who could keep the programme at the top of the ratings.

This is when Frankie Howerd, in the anxious and frustrated state that he was now in, somehow convinced himself that this was the show that could catapult him high over Grayson and straight back to the top of the business. Already excited just by the thought of it, he picked up the telephone and called Bill Cotton; once he was through, he gabbled away, telling the executive that he felt he was perfect for the job, had lots of ideas to make it his own, and would gladly audition and jump through whatever hoops were deemed necessary in order to win over any doubters.

Cotton, listening to all of this, felt increasingly awkward. 'I loved Frank,' he would tell me, 'I had always been a huge admirer of his talent, but he was a stand-up comedian - a truly brilliant stand-up comedian - and not a host. If he had a script for a routine, learnt it and mastered it, then he'd be superb, but on a show like The Generation Game - he didn't have the discipline for it, or, by that stage, the energy. There were so many different things that needed doing, so many technical things to get right - with Frank it would have been chaos! So I said no, as tactfully as possible. I told him we'd look out for something else for him, which we did do, but, no, we couldn't consider him for The Generation Game.'

If that was not a hard enough blow for Howerd, the subsequent news of who had been chosen to host the show would be almost unbearable. Cotton, initially, had wanted Cilla Black, a good friend of Howerd's, but she had turned it down. Then he had considered a number of alternatives, including Jimmy Tarbuck, before eventually making his choice: Larry Grayson.

Howerd was furious. He felt that, if they had decided that he would have been too nervous, easily-flustered and prone to confusion to host the show, then why did they go for Grayson, who also looked as though he would be too nervous, easily-flustered and prone to confusion to host the show?

It was a fair enough question, but there was a degree of reason in the BBC's apparent madness.

First, they had decided, after some discussion, that they wanted someone who would not seem like they were simply trying to copy Forsyth; they wanted someone different. Second, they felt that Grayson, unlike Howerd, would actually take advice, follow direction, put in the hard work and have the energy to keep the show moving at the right pace. Third, they believed that Grayson would be better with members of the public than the well-meaning but sometimes cantankerous Howerd. Grayson seemed, in short, far more malleable and manageable.

The irony is, however, that the BBC, after Grayson stumbled his way through a quite dramatically shambolic (and never broadcast) pilot for the show, was forced to revise the format in such a way that it was now far better-suited to Howerd as well as Grayson. 'Larry had struggled with a few aspects of the show,' Bill Cotton would tell me, 'but what he'd really been hopeless trying to do was a really crucial thing: explaining to the contestants, in clear and simple English, what each game required them to do. So we solved that problem by handing over that duty, and a couple of others, to the woman we'd booked to be Larry's Girl Friday, Isla St Clair. After that, Larry was freer to relax and be more himself.'

Howerd, watching at home once again, would no doubt have thought that Grayson was now freer to be more like him. The sense of rejection hurt so much that, in future, he would do his best to block out the show's - and Grayson's - existence.

All of this was rather unfair on Grayson himself, who was a kind-hearted and decent man without any desire to cause upset or distress. Yes, his act was indeed highly derivative of Howerd's, and he certainly owed him a huge debt not only for his influence but also for working so hard to make their kind of camp humour acceptable on mainstream TV, but he also had his own distinctive characteristics, as well as an engaging and endearing personality, that explained why he was now enjoying so much success.

There was also, for all of Howerd's fears, just about room enough for both of them on the nation's screens. Grayson would continue with The Generation Game until 1982, and then remained fairly busy until he started to drift into semi-retirement. Howerd, although he struggled to find a decent enough starring vehicle, still received plenty of work, and, by the 1980s, would enjoy yet another surge in popularity as he was embraced by the student community.

Theirs had been a strange rivalry. It was very one-sided, but very intense, and, mercifully, far less directly and personally wounding than the clash between Trinder and Forsyth.

What, though, do these two clashes teach us about the world of comedy in particular, and show business more broadly? The answer, beyond the banalities about the competitiveness and insecurity inherent in the profession, is surely that, when other unwilling duos find themselves stuck in the same situation, they and those around them should try harder to appreciate, and show compassion for, those suffering most from the transience of stardom and fashion, and trust a little more in the affection felt by the audience for the authentic as well as the artful.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out moreSunday Night At The London Palladium - Volume One & Two

Debuting on ITV's opening weekend in 1955, Sunday Night At The London Palladium swiftly established itself as one of the weekly televisual highlights for the British viewing public. Lasting fourteen years until 1969 (and enjoying a revival in the 1970s), the show gained average viewing figures of 14 million and Top Ten placings most weeks, and was one of the core shows that helped establish commercial television in the UK, transcending class, denomination and age group an unquestionable success which still provides a high benchmark that today's variety shows can only aspire to.

The show's hosts included Tommy Trinder, Bruce Forsyth and Jimmy Tarbuck, and among its numerous guest performers were The Beatles, Pete and Dud, Frankie Howerd, Morecambe and Wise, Sammy Davis Jr., The Supremes, and Judy Garland.

This 5-disc set contains the previous two released volumes: the highlights of what little of the series remains in ITV's archive.

First released: Monday 10th October 2011

- Distributor: Network

- Region: 2

- Discs: 5

- Catalogue: 7953587

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.