That's Me In The Corner: Four Comedy Stooges

You don't really see them these days: those odd, idiosyncratic, seldom-speaking comic characters - performers whose entire raison d'être is to be the recurring butt of a well-known comedian's jokes. Go back forty years or more, however, and they were common sights on the comic landscape, enjoying a strange kind of success from serving as a stooge.

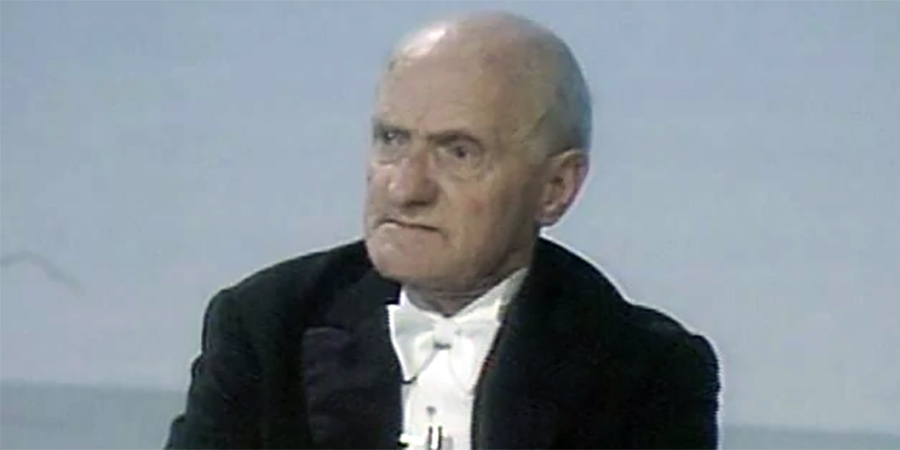

One of them, with one of the longest careers, was a lugubrious-looking little man named Johnny Vyvyan. From the mid-Fifties through to the early Eighties, he was a fixture on British television, popping up in many of the most popular comedy shows of the era.

Imagine an under-fed pug standing on its hind legs, dressed in a cheap suit. That was what Johnny Vyvyan looked like. One half expected him to be on a lead.

Nicknamed 'The Grinless Wonder', he had a small, round head, with big, dark, sad eyes, a stubby dummy's nose and a narrow, pouty mouth. He always seemed slightly lost in thought, his expression frozen midway between belligerence and bewilderment as the tall funny man standing nearby either barked orders at him or told jokes about him.

Born in 1924 in the small town of Boggabri in north-western New South Wales, Australia, as John Haddon McGuire, he had shown an interest in showbusiness from an early age, and, straight after leaving school, he moved down to Sydney to work in a theatre there as a stagehand. No one quite knew what to do with this would-be performer: he was only four-feet eleven inches tall (in stark contrast to his brother, Milton, who was a towering six-feet three), so any suitable acting roles were few and far between, and even in terms of a variety act his inability to sing, dance or do stand-up suggested that his future was more likely to be behind the scenes rather than out in the spotlight.

McGuire, however, remained undeterred, and, after changing his surname to the more memorable-sounding Vyvyan, he started working on his ability to perform some acrobatic slapstick routines, as well as exploiting his unusual looks as a straight-man. He also started sending in comedy scripts to local radio stations, and, much to his delight, some of his material began being used on comedy shows. In 1948, buoyed by his recent writing successes, he sailed off to Britain in the hope of starting a new life and cultivating a career in comedy.

Initially, however, his attempts to break into showbusiness in London were greeted with much the same sort of bemusement as he had encountered back home, but then he got lucky: he met Derek Roy.

Derek Roy was a comedian - a very mechanical, unoriginal sort of gag teller, but much in demand for his safe and reliable style of patter. Already, by the late 1940s, a regular on the BBC's hugely popular radio show Variety Bandbox (where he alternated - and enjoyed a friendly mock rivalry - with a young Frankie Howerd), he would go on to star in his own show, called Happy-Go-Lucky (1951), as well as host the UK version of the American-originated TV show People Are Funny (1955).

Not all of his many writers could stand what he did to their material - Spike Milligan, especially, hated what he regarded as the comedian's incompetence at 'selling' a gag without resorting to the most brazen tricks of the trade ('When he came to the punch line,' Milligan fumed about his radio performances, 'he put a funny wig on to get a laugh') - but he was an amiable enough human being, and his chronic need for new material meant that his shows were magnets for anyone starting out who felt they could come up with comic ideas (among his 'discoveries' would be Ray Galton and Alan Simpson).

Fortunately for Vyvyan, Roy was a very approachable man - he'd happily stop and listen to anyone who approached him at the stage door, in a pub or on the street, partly because he was naturally sociable but also because he was always on the lookout for free or very cheap stories and sketches from people new to (and naïve about) the business - so the recently-arrived Australian sought him out and asked him for work. Roy asked for some samples of his writing, liked much of what he read, and promptly added him to his ever-expanding network of gag-suppliers.

What precisely happened next has, frustratingly, been left lurking somewhere deep in the mists of time, but, for some reason or other, Roy went on to appoint Vyvyan as his secretary, lodger and all-purpose in-house dogsbody. He continued to use the odd bits and pieces of his comic material, but was mainly happy to let him deal with all of his administrative affairs.

They made a decidedly odd couple. Whenever producers or writers would visit the Roy residence (which was situated inside the large Art Deco apartment block Du Cane Court in Balham, South London) they usually found (regardless of the time of day) the comedian sitting up in bed and the diminutive Vyvyan hovering around looking almost aggressively melancholic.

Theirs was not, as far as we know, a gay relationship - both men, at least publicly, identified as heterosexuals (as by law in those days they would have to have done), and Roy, at the time, was about to marry his stage partner, the glamorous dancer and comic performer Rona Ricardo (the first, it would turn out, of four wives) - but it was certainly a bond that generated a fair amount of discreet gossip, simply because it seemed such an eccentric arrangement.

Budding scriptwriters would have to sit by Roy's bed and read out whatever gags or routines they had managed to produce for that particular week. The comedian, meanwhile, would lie there partly-hidden under the sheets, his head propped up by a pillow, staring at the ceiling while murmuring 'yes' or 'no' in response to each portion of patter they offered. At the end of the whole process, he would ring a small antique silver bell on his bedside table to summon Vyvyan, who would enter the bedroom carrying a metal money box, from which he would pay the writers in cash, at the rate of five shillings per gag, and then escort the visitors back out of the apartment.

Roy soon took to using Vyvyan occasionally on stage in the odd routine, having him come on (sometimes as a 'plant' in the audience), look miserable and awkward, and absorb a few sarcastic barbs, before slouching back off again. It was not long before other comedians, seeing how this strange little man (who had come to be labelled 'The Face') seemed able to resist cracking a smile no matter how much laughter was going on all around him, started 'borrowing' him from Roy to serve as a stooge in their own acts.

Peter Sellers, for example, used him in 1952 when he played the Palladium, and the likes of Harry Secombe, Jimmy Edwards and Tony Hancock followed soon after. He was still contributing material for several radio shows (including Jon Pertwee's 1953 series Pleasure Boat), but from now on his main role would be as a novelty sidekick for comics.

The agency Associated London Scripts, once it was established in the mid-1950s, signed him up on to their list of writers and performers, and that ensured that he became part of a stellar circle that included Spike Milligan (who started using him on Son Of Fred), Galton & Simpson (who started using him on the TV version of Hancock's Half Hour) and Eric Sykes (who started using him in just about everything that he did).

For the next couple of decades or so, Vyvyan seemed near-ubiquitous as far as comedy shows were concerned. He appeared alongside Tommy Cooper, Tony Hancock, Sid James, Benny Hill, Frankie Howerd, Alfred Marks, Charlie Drake, Hattie Jacques, Des O'Connor, Bruce Forsyth, Les Dawson, Mike Yarwood and many others. Everyone seemed to want to use him either as a slightly truculent-looking character in the background of their sketch or sitcom or as a stone-faced stooge in some of their comic routines.

In a rare interview he gave in 1978, he would insist somewhat improbably that, away from the cameras, he was actually a perfectly cheerful person ('You should see me at home,' he protested, 'I love to laugh my head off'), and he confirmed that it was quite a strain to maintain his sad-faced expression ('They all try to make me smile. The things they say in my ear which the microphones won't pick up are unprintable'), but he knew that he had found a niche, and he had no ambition other than to keep on doing what he was doing. 'If I did laugh,' he reasoned, 'it would kill me stone dead. Look at me, I'll never play Hamlet. Why change a winning streak? Too many people change their image - and they are never heard of again'.

He thus worked on steadily until close to the end of his life, which came prematurely, at the age of 55. After suffering from heart problems for a number of years (he'd only recently had a pacemaker fitted), he was found dead in his bungalow in Ewhurst, near Godalming in Surrey, on 3 September 1984, although it was thought he had probably passed away two or three days earlier.

He would have been in favour of the headlines that marked the sad occasion: 'Grumpy-faced comic dies'. His face, after all, had been his fortune.

One of Vyvyan's contemporaries, who enjoyed a similar cult status as a stooge, was Arthur Tolcher. Like Vyvyan, he had not set out to play such a menial role on stage - he had actually spent many years previously as a specialist musical act - but he ended up being known, by the majority of the British public, for being told repeatedly by Morecambe & Wise: 'Not now, Arthur!'

Born Arthur John Stone-Tolcher in Bloxwich, Walsall, in 1922, he was brought up by parents who were themselves music hall performers. His father, Charles, was described initially on his billing matter as an 'Anglo-Indian Comedian and Facial Artiste,' and then later as 'the Funny Australian Comedian,' and later still (once he'd finally remembered that he was English) as 'the Irreproachable Comedian,' while his wife, Beatty Tolly, was a singer and dancer.

Arthur started treading the boards at the tender age of eleven (billed as 'The Wonder Boy Harmonica Virtuoso'), and was already getting on air by the age of fourteen (thanks in part to all the letters his mother would keep sending in) when he started performing his act on the BBC's Midland Regional programmes; one year later - in 1937 - he appeared in his first pantomime alongside his father.

In 1940, he joined the cast of the impresario Bryan Michie's 'discovery' show, Youth Takes a Bow. It was here that he struck up a friendship with two other eager young solo performers, the comedian Eric Bartholomew and the song and dance man Ernie Wise - later, of course, Morecambe & Wise.

'Ernie was lonely and I often used to slip down into his dressing room for a chat,' Tolcher would later recall. 'We were both kids away from home. One afternoon we stood at the side of the stage to watch the boss auditioning new boys for the show. This tall, sallow kid with glasses, a kiss curl and trousers half way up to his knees came on stage. He had an oversized lollipop in his hand and he sang a daft song called I'm Not All There. His name was Eric Bartholomew, and he had us in hysterics even then'.

The very likeable and permanently cheerful Tolcher was an excellent harmonica player (he would play a number of sizes, from standard chromatic all the way down to a custom-made midget model - 'one inch long and eight notes' - which he would move around the inside of his mouth as he played it). The problem was that, even when the variety circuit was still very active, an act featuring one man and his mouth organ was never going to be a bill-topping attraction, so while, after the war, the now-renamed and reunited Morecambe & Wise began progressing in their shared comedy career, Tolcher found himself falling further and further out of fashion.

By the 1960s, he was back in the Black Country, living in a council house in Bloxwich with his widowed mother, keeping budgerigars and breeding newts, still upbeat and uncomplaining but increasingly reliant on the annual cycle of summer seasons and pantomimes to keep him busy. His doting mother, when interviewed late on in the decade, admitted that the decline of live theatrical entertainment, in spite of her son's positive nature, had hit him hard: 'Terrible heartbreak for Arthur, that is'.

Eric and Ernie, however, had not forgotten their old friend, and, in the early 1970s, they devised a recurring gag for him on their TV show. As a sign of their respect and affection, they told the press that they had wanted to use him for some time only to find that he was always too busy, but in truth he had been asking them for a while to see if they could find him some work.

The gag they came up with was actually 'borrowed' from a routine all three had seen during their Youth Takes a Bow days more than thirty years before. A trumpet player named Gee Jay would keep coming on stage, only for the host Bryan Michie to keep shouting out, 'Not now!' Eric remembered it, and the laughs it always got, so he and Ernie adapted it for Arthur.

Every now and again, in between sketches or just after the stars had left the stage, Tolcher ('He's a man of many parts,' Eric would say. 'Unfortunately, one or two of them are not working') would sneak up, dressed in white tie and tails, and, sensing that the coast was clear, he would walk towards the microphone, smile excitedly, put his harmonica up to his mouth and start playing the Spanish Gypsy Dance - only to be stopped a few bars in by either Eric or Ernie, or both, suddenly reappearing to shout: 'Not now, Arthur!' Then, head down and shoulders slumped, he would walk disconsolately back off the stage.

It would sometimes get even crueller. The show would be coming to an end, Eric and Ernie would sing their closing song, take a bow and dance their distinctive way off, and then Arthur, who had been in hiding, would come racing on to try again, blow into his harmonica... and the screen would go blank.

Suddenly, as a result of such comic exposure, Arthur Tolcher found himself a nationally-recognised figure. Everywhere he went, people driving past in cars, pausing in shops or passing by on the streets would shout out, 'Not now, Arthur!' He was thrilled.

He even made plans, coming up to Christmas in 1974, to record his very first album, which was set to be called, of course, Not Now, Arthur!. Unfortunately for him, however, it was discovered that the comic actor Arthur Mullard was ready to release his own novelty single, called Not Now Arthur, and the project ended up being scrapped. Tolcher soon got over the disappointment; he was enjoying every fragment of fame that was finally coming his way.

Morecambe & Wise did not just use him on their TV shows. They also used him on what they called their 'bank raids' - those brief provincial 'in and out' tours when they would take their old stage show to towns and cities up and down the country and charm their masses of fans with some tried and tested routines. Tolcher would sometimes travel ahead, pick up a local newspaper, see if there was the odd topical reference they might want to slip into the show that night, and then meet up with them for a cup of tea and a chat.

'Just to be there with those two is a tonic,' he said at the time. 'It's as if the years roll away and we are all kids again'.

He would remain a semi-regular on all their BBC shows right through to their penultimate Christmas show in 1976, and even made a cameo appearance in one of their later specials for ITV. The bond between him and them had lasted almost forty years, and it ensured that, while the public might have thought of him merely, though very fondly, as a comic stooge, he meant an awful lot more to Morecambe & Wise.

He died on 8 March 1987, aged 64, in his beloved Bloxwich. A recording of him and his harmonica was played on that sad day - and this time it was played all the way through.

Characters like Vyvyan and Tolcher seemed irreplaceable, but when Benny Hill came up with the notion of using a little old bald-headed man as his stooge, he liked the idea so much that when the first one retired, he went ahead and hired another one. The first man to have his scalp smacked repeatedly was Jackie Wright, and the second was Johnny Hutch.

The Irish-born Jackie Wright was perfect for the part. He was four feet two inches tall, a wiry little man, with a light-pink landing patch of a balding head, dark little darting eyes, black-rimmed spectacles and a slightly jutting chin that jabbed anxiously away at space when he spoke.

Born in 1904 in Belfast, he had spent his first few adult years assembling cars both at home and in the US before, belatedly, drifting into showbusiness, first as a musician (he played the trombone) and then as a singer, dancer and comic. Billing himself first as 'Jackie Wright - the little bundle of mischief' and then, once he started losing his hair, as 'The Blonde Bombshell,' he gradually made quite a name for himself touring around Northern Ireland from the Thirties through to the early Fifties ('He's an entertainment in himself,' wrote one critic admiringly of his multi-tasking talents), before venturing out further afield (basing himself in Walworth, South London).

Benny Hill spotted him as an extra in a number of TV shows (including fleeting scenes as a drunk in a couple of episodes of Z-Cars), and couldn't stop thinking about the comic potential his rather vulnerable features suggested. He eventually recruited Wright for his own comic troupe of quirky characters, but only after some persuasion - having actually more or less retired from performing at that point in his life, Wright was sceptical about taking on such a high-profile commitment, but Hill finally won him round. Wright first started having his head slapped in the 1968 series of The Benny Hill Show, and, from that point on, he was a regular.

Already well into his sixties when the relationship began, Wright was content to do whatever Hill wanted him to do. He had no burning ambitions by that stage in his career - he was just happy to be enjoying a bit of belated fame.

'I don't want to work all the time,' he told a journalist in the early Seventies. 'Three months of the year with Benny is fine. I like what I do now. If I did more it would be work. I don't want that'.

Thanks to his chain-smoking (he could barely get through a scene without having at least the odd furtive puff), he had a rasping 'Norn Iron' accent that he used to excellent effect, but most of his appearances were in sketches where the only sounds were the dubbed 'pat-pat-pats' that accompanied Hill's speeded-up slaps on his head. One of Wright's few notable speaking parts was as 'Fred Needle', a surgical appliance outfitter, who was a contestant being questioned by Hill as 'Magnus O'Magnussen' in a memorable parody of Mastermind.

MAGNUS: You have chosen to answer questions on general knowledge, is that right?

FRED: ...Pass.

MAGNUS: What is celery?

FRED: High class wages.

MAGNUS: Anaemic rhubarb. What is baloney?

FRED: Sausage.

MAGNUS: Baloney is where you find the hem of a nice girl's skirt. What do you call Russian napkins?

FRED: Pass.

MAGNUS: Soviets. Why do cows wear bells round their necks?

FRED: Cos their horns don't work.

MAGNUS: Well done. And you will be. What does it mean when your palm itches?

FRED: Visitors are coming.

MAGNUS: And when you itch all over?

FRED: They've arrived.

MAGNUS: O'Duffy fell down two flights of stairs with a pint of whisky, none was spilled. Why was that?

FRED: He kept his mouth shut.

MAGNUS: What is hire purchase?

FRED: Er, hire purchase is feathering your nest with a little down.

MAGNUS: Hire purchase are what brave budgies stand on. What is a bachelor?

FRED: A man who hasn't thought seriously about getting married.

MAGNUS: A man who has thought seriously about getting married. What is an asset?

FRED: Er...a little donkey.

MAGNUS: An ascot?

FRED: A little donkey's bed.

MAGNUS: A pathologist?

FRED: Erm...a man who can find his way through a wood.

MAGNUS: Unabridged?

FRED: Um...A river you have to wade across.

MAGNUS: What is it that a man does standing up, a woman does sitting down, and a dog does with one leg raised?

FRED: Pass.

MAGNUS: Pass what?

FRED: I don't know the answer.

MAGNUS: The answer is: 'Shake hands'. I am nineteen years old, I have a lovely soft speaking voice, a gorgeous figure, a passionate disposition, soft red lips, eyes like pools of liquid, I own a pub and I don't drink. Who am I?

FRED: Who cares - kiss me!

Most of the time, however, it was more of the same pat-pat-patting, and Wright never minded a bit. After so many decades of touring as a solo act, he finally felt part of a family. 'If we are on location on my birthday,' he said, 'Benny sees I get a cake and gives me cigarettes as a present. We have a party'.

He only gave up, eventually (in 1983), because of his declining health. He died, after a long illness, on 22 January 1989, aged eighty-four, in a hospital in his hometown of Belfast. Benny Hill, upon hearing the news, said that he was 'saddened beyond words'.

He hadn't quite been able to resist, however, finding a replacement. The man whom he had chosen was, in many ways, the most remarkable of this quartet of stooges: a performer called Johnny Hutch.

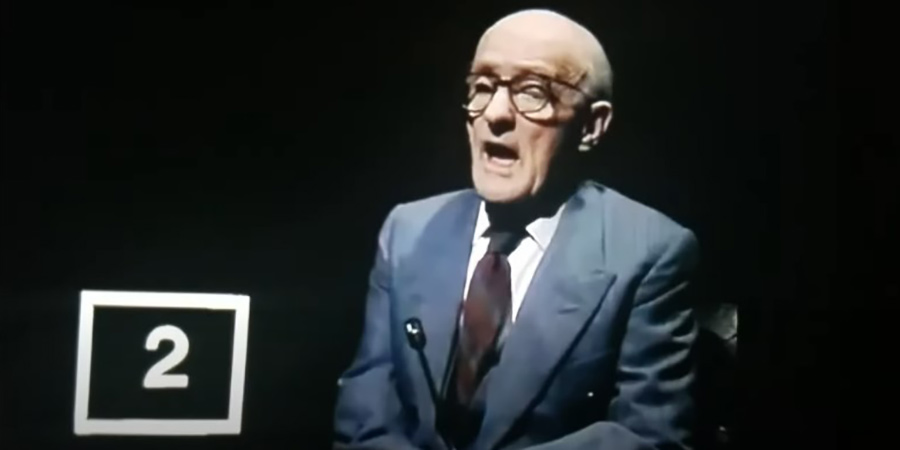

Johnny Hutch became Hill's new bald-headed slap-magnet in 1988. He was, however, a considerably more accomplished character than that.

Born John Hutchinson in Middlesbrough on 8 August 1913, the son of a docker, he was a veritable force of nature. Once he could walk and make sense of the world around him, he started throwing himself about in order to get a reaction from anyone who happened to be watching. When he found ways to elicit some laughs, his physical daring grew ever more striking.

He was just fourteen when he answered an ad in the local Gazette calling for 'a small boy for Empire stage door'. He ended up on top of a human pyramid of acrobats called the Hadji Mohamed Troupe.

Later renaming themselves The Seven Royal Hindustans, they trained Hutch, as he was now called, in all of the smart arts of tumbling, and took him with them on their tours of Britain and abroad. Precociously gifted - he became the first English acrobat to perform a double twisting somersault - he spent the next few decades, aside from his wartime duties, leading a succession of high profile acrobatic acts, culminating with a comedy tumbling troupe known as The Halfwits.

He also set up The Johnny Hutch School of Professional Acrobatics and Stagecraft ('Producers of High Class Specialty Acts, Knockabout and Fight Sequences, Traditional Trap Routines'), helped establish Zippos Circus, served as a stunt coordinator for the Royal Shakespeare Company - for Marlowe's Tamburlaine The Great (1992) and Rostand's Cyrano de Bergerac (1997) - and as a consultant on the movie Chaplin (1992), and trained the Teletubbies, as well as, amazingly, winning the Circus World Championships in 1976 at the age of sixty-four with a full-twisting backward somersault.

He was an extraordinary physical performer. Sir Antony Sher, who was coached by Hutch for Tamburlaine, would recall: 'I shall never forget the surprise of walking into the gym for our first session and discovering that my teacher was a diminutive man of seventy-nine. In reply to my "Hello, how are you?" he said in a broad Yorkshire accent, "No all right, ta, just a bit of arthritis in me wrists - it stops me walking on me hands, and I always like to start the day with a little walk on me hands". I was speechless. My own father was roughly the same age, and could barely walk on his feet. Who was this man? Quite a phenomenon, it turned out'.

Benny Hill had known and admired Hutch for years, having watched him from the wings on countless occasions when they were in the same variety shows. Once Jackie Wright retired, therefore, and Hill started to miss the main character that he had played, he didn't hesitate to sign up Hutch.

Hutch lacked the comic vulnerability of the whippet-thin Wright - the stockier-looking successor always seemed quite capable of smacking the smacker back - but he certainly brought some acrobatic energy to the role. He could bend his legs to look ridiculously bow-legged, he could exploit his modest five-foot frame for laughs and he could propel himself wherever Hill wanted to throw him.

His limitations when it came to delivering comic dialogue meant that he was usually restricted to short and sharp badinage - for example: MAN: 'Have you got a book called Man: The Superior Sex?' LIBRARIAN: 'You'll find it over there - under fiction'. He could, nonetheless, make a physical scene all the more effective because of his technical expertise.

He probably would have continued to be Benny Hill's stooge indefinitely, but The Benny Hill Show was cancelled, rather abruptly, in 1989 and Hutch was left to explore the many other offers he was receiving. By that time he was in his mid-seventies, but still fighting fit and ready for further adventures (and he would work on until his death, aged ninety-three, in 2006).

As far as TV fame was concerned, however, Hutch - like Vyvyan, Tolcher and Wright before him - remained defined by his memorable spell as a stooge. None of them would have minded. Being remembered by millions for being 'that man with the miserable face,' or 'him who never got to play his harmonica,' or 'the little old chap who always got his head slapped,' might not have matched the ultimate end of their ambitions, but all four were grateful, nonetheless, for the special place it gave them in British comedy history.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more