Sounds Familiar: The secret history of US comedy on UK radio

In 1949, the BBC issued its employees with a set of rules - The BBC Variety Programmes Policy Guide For Writers and Producers - with a view to improving broadcasting standards. Soon known informally as 'The Green Book' (because of its khaki covers), it listed all of the so-called 'taboos' - which included advertising; expletives; impersonations of public figures; libel and slander; biblical and political references; drink; physical or mental infirmities; and 'vulgarity'. One of the most misunderstood of these stern admonitions, however, is the ban on 'American material' and 'Americanisms'.

The caution in question declared:

Various fairly obvious factors, such as American films and the fact that much modern popular music originates in America, tend to exert a transatlantic influence upon our programmes. American idiom and slang, for instance, frequently find their way quite inappropriately into scripts, and dance band singers for the most part elect to adopt pseudo American accents. The BBC believes that this spurious Americanisation of programmes - whether in the writing or in the interpretation - is unwelcome to the great majority of listeners and incidentally, seldom complimentary to the Americans.

There is and always will be a place in programmes for authentic American artistes and material but the BBC's primary job in light entertainment must be to purvey programmes in our own native idiom, dialects and accents. The 'Americanisation' of British scripts, acts and performances is therefore most actively discouraged.

This particular prohibition has been interpreted by some later commentators - especially by a few blinkered academics who had never even bothered to explore the relevant archives - as being mainly or solely to do with some kind of backward-looking and insular idea of 'Britishness', or a sign of 'post-colonial insecurity', or merely a snooty form of xenophobia. The truth, however, is much messier, and more intriguing, than that.

The fact is that - as a number of writers and producers working at that time have since confirmed to me - there was a real fear of a potential scandal lurking beneath the surface of these words. Yes, some of the BBC's executives were indeed unimpressed by hearing performers from Putney or Preston trying to sound as if they hailed from Brooklyn or Boston, and, yes, they were also keen to see more programmes engage with distinctively British themes and situations rather than ersatz American ones, but there was far more to it than that. They were also desperate to stop British programme-makers stealing from American shows.

The practice - a kind of dark web of derivation - had been going on since the 1930s, and throughout the Second World War, but, by the late 1940s, it had spread alarmingly throughout British entertainment and was basically out of control. A whole generation of budding comic writers, desperate to make a mark in the medium, had realised that the easiest way to come up with an abundance of good quality material was to 'borrow' it from American radio, where, far more so than in Britain, whole teams of experienced writers were churning out masses of gags on a weekly basis.

The main source of it all, for the British, was shortwave radio. Warm up the wireless, they realised, and they could have American writers, quite unwittingly, supplying free scripts for British shows.

'We all knew it was going on,' Eric Sykes (who never himself resorted to such stratagems) would tell me. 'I mean, the writers knew, maybe not the bosses. You'd hear about it: they'd sit by the radio, pen and pad at the ready, headphones on or ear pressed against the speaker, and they'd scribble away, getting as many gags down as they could. Some of them had girlfriends or sisters who were secretaries, so they'd enlist them to sit alongside them writing it all down in shorthand. And then they'd type them up and send them in! A lot of them would mix in the gags with their own stuff, but some would just lift whole sketches and routines. The smart ones, the careful ones, would "translate" them, you know, replacing things like "sidewalk" with "pavement" and "elevator" with "lift," but the lazy ones probably didn't even notice that much and the odd phrase would get left in. They were in too much of a hurry to get paid.'

There were many shows in the market for such material. Most British radio shows of the time were modelled on American sources.

There were, for example, all of the variety shows, such as Band Waggon, ITMA (pictured), Variety Bandbox and Stand Easy, which followed the standard US formula of fast-paced sketches, songs and stand-up, hosted by rapid-talking hosts such as Tommy Handley, Charlie Chester, Derek Roy and Arthur Askey. Being American formats, they naturally fed off American scripts, and so, week after week, British writers found it all too easy to tailor their transcripts for a quick commission.

Brad Ashton, another very busy scriptwriter of the time, would later note that there was fierce competition to hear the original US shows as quickly as possible and gut them all for their best gags. 'Bob Monkhouse usually beat everyone else. He had an excellent radio set and was really quick to recycle it all. Jimmy Grafton [the pub owner, part-time writer and early champion of The Goons] had the best aerial - he was able to pick up shows from all over the place. But lots of us were at it every week as part of the usual routine.'

Bob Monkhouse himself later admitted as much. He would claim that he and many other comic writers shared a common affliction throughout the 1950s called 'shortwave ear' (excessive redness, flaky lobes) due to pressing their heads so close to their radio sets in order to listen to shows on the American Forces Network.

It was hardly a surprising phenomenon. Whereas American radio shows generally had large and well-established teams of extremely self-disciplined and industrious writers producing their comic material (Bob Hope, for example, paid for eight of them out of his own salary and used them for everything that he did), British broadcasting was still reliant on a decidedly amateurish and disorganised process for building up its scripts.

Some stars would insist on using their own 'private' writer (such as Frankie Howerd did, for several years, with Eric Sykes (pictured)); other stars (such as the less-than-choosy Derek Roy) would turn up at the rehearsal room with a few gags and routines they had bought from total strangers at the stage door and simply slipped them into an existing script; sometimes a BBC producer would hire a regular writer and monitor his work in-house; and sometimes one or two producers, out of desperation, would cobble together some material from old scripts, or even draw on their own ideas, in order to get a show out and on air. 'You usually didn't have the luxury of being able to sit back and ponder where you'd heard something before,' one programme-maker told me. 'You were under pressure to just meet your deadlines and get on with the next thing.'

It was thus a fairly safe context for the copyists. Only a relatively tiny proportion of the general population was tuning in to any shortwave broadcasts, and, within the BBC itself, whatever was being listened to on a regular basis was for other reasons rather than mere amusement. Without any effective means of general or centralised surveillance, therefore, there was more than enough informality, fluidity and chaos to ensure that comic material kept on creeping in from all kinds of murky sources.

There were, of course, some producers who were sufficiently familiar with American shows and performers to spot some of the lines, sketches and routines that had been imported from across the Atlantic, and would either cut such material from the scripts or see that they were re-written to disguise their origins. Others, however, were either too busy, or too naïve, to notice, and the borrowings went in without any immediate doubts arising.

It also did not help, of course, that radio in those days was regarded as such a transient medium. Shows were planned, recorded, broadcast and then, usually, forgotten.

Once enough of the executives finally realised what had been happening, however, it was obvious that something would have to be done. Acknowledging the problem publicly would have been disastrous for the Corporation, leaving itself open to innumerable law suits as well as wrecking its reputation, and so, at the end of the 1940s, The Green Book dealt with the issue more discreetly.

Unfortunately, however, the strategy failed to work. The Green Book's self-consciously noisy embargo on American material was certainly a shot across the bows, but, after the initial fright of having been found out started to fade, many writers simply carried on as before, only rather more cautiously, with all of the 'Americanisms' now safely edited out. It was simply too lucrative a practice for most of them to surrender: why struggle to come up with enough decent comic material to fill one script (if that) every week, when you could avail yourself of the best that a whole other country had to offer and fill several more scripts every month?

The BBC, as a consequence, was left to endure several more years of the censorial equivalent of the game of 'whack-a-mole', pouncing on one after another case of plagiarism whilst multiple new cases kept popping up in various other places. The copiers merely got craftier, and the regulators more resigned, and the practice continued far into the 1950s.

The worst abuses now occurred on those shows that were largely controlled by their own stars. Arguably the most egregious example of this type of personality-led programme-making was the family comedy Life With The Lyons.

One of the first sitcoms broadcast on British radio (and the template for such later shows as My Family and Outnumbered), it starred the real-life married couple of Bebe Daniels and Ben Lyon, along with their two children, Barbara and Richard, and ran from 1950 to 1961. The American-born Daniels and Lyon had been actors in Hollywood, but had been based in England since the start of the Second World War, contributing to such popular radio shows as Hi, Gang!. Their commitment to the national cause had made them much-loved honorary Britons.

Life With The Lyons (pictured) was their first bona fide starring vehicle, and it saw the redoubtable Bebe assume an unprecedented amount of control over its production. Using her and her husband's own London town house - on Southwick Street, just behind Marble Arch - as the programme's work base (as well as the show's situation), she appointed herself as the official writer of the show, but privately hired two professional writers at a time to actually come up with the scripts.

Those who wrote for the sitcom (the list would include, at various stages, Ronnie Hanbury, Brad Ashton, Bob Block and Bill Harding) would later describe it as 'like being in a prison', because the ultra-demanding Daniels expected them to be at her beck and call for twenty-four hours a day ('The fact that we had other commitments was irrelevant to her,' one of them told me. 'You'd be working on something for another show or performer, or maybe you'd just settled down for dinner, or be taking a bath, or settling into bed, and the phone would ring, and it would be Bebe: "I need a re-write, I need this, I need that". She really cracked the whip').

They were required to work in a room on the top floor of her house - where there were two tables, two chairs and two typewriters - and come up with comedy as if they were in a factory. 'There were no illusions,' one writer said. 'You were clocking in and you would need to produce a certain amount of stuff before you could clock out again.'

It was here that, each week, they had to take Bebe Daniels's one-page storyline for the next episode and turn it into a script, which always had to be broken down into eight separate scenes, with one writer producing scenes 2, 4, 6 and 8, and the other one coming up with scenes 1, 3, 5 and 7, each one of which had to consist of precisely 500 words. These sections would then be handed over to Bebe's three private secretaries - June, Joyce and Joan - who would (because Daniels herself realised that she lacked proper comic judgement) go through the material independently of each other, each one using a different-coloured pencil in order to signpost lines deemed 'B' for a big laugh, 'A' for an average laugh and 'S' for a small laugh. Daniels would then collect these scribblings and depart for a secluded section of the house, where she would sum up the consensus and decide on what needed to be changed.

The writers themselves, meanwhile, were allowed downstairs at 10:30am each day for a brief tea break in the kitchen - except on Thursdays. They never knew what happened on Thursdays; it was a mystery that festered while they kept toiling away upstairs.

They were barred from coming down on Thursdays, we now know, because Thursdays were the days when a very large package arrived from America. Unbeknownst to the writers, this package contained multiple reel-to-reel recordings, made by Ben Lyon's cousin in Missouri, of every major US radio comedy show from the previous fortnight.

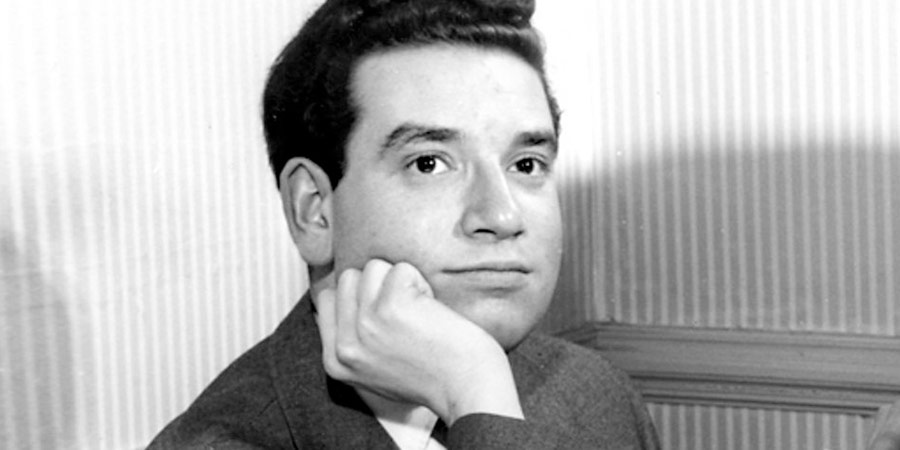

Daniels had secretly arranged for the young and ambitious Denis Goodwin (pictured), a former Dulwich College student and future scriptwriting colleague of Bob Monkhouse, to turn up each week to listen to all the tapes, transcribe them, and then select the best jokes, dialogue and sketches. These would then be broken up and filed away in special subject-specific folders, such as 'Travel', 'Food', 'Kitchen Appliances', 'Parents', 'Children', 'Automobiles', 'Maternity' and 'Money'. Goodwin was also required to use the material to fill about ten pages of 'ideas' each week which could be slipped into the script for the latest episode of Life With The Lyons.

'We couldn't figure it out for a while,' Brad Ashton would say. 'We'd get these pages handed to us, with all these comic lines on them, and each one would have these initials after them - "BH", FKB", and so on. And eventually we realised, "FKB" meant Father Knows Best - a big American radio show of the time - and "BA" meant Burns and Allen, you know, "BH" - Bob Hope, "JB" - Jack Benny, "SA" meant The Steve Allen Show, and so on and so on.'

What Daniels was thus doing, in her self-appointed role as 'head writer', was recycling as much material as she could from the shows of her homeland. Every instalment was stuffed with imported gags and bits of dialogue (which, thanks to Bebe and Ben's authentic American accents, were easier than ever to hide in plain sight and sound), but there were also plenty of occasions when entire episodes were loosely re-worked copies of certain US shows. An edition of Father Knows Best called A New Housekeeper, for example, became a Life With The Lyons episode entitled The New Maid, and an old instalment of The Great Gildersleeve (another hugely popular US domestic comedy) called The New Neighbor was revised as The New Neighbours, while several storylines from The Adventures Of Ozzie And Harriet and My Favorite Husband (two more very similar family sitcoms) were lifted for the Lyons.

It was in this way that the show became, right under the noses of the BBC's bosses, a kind of clandestine weekly British omnibus of the best comic material on American radio, adopted free of charge. Some of the second-hand situations and exchanges might have seemed somewhat bland and impersonal in their new environment, but the vast majority of listeners, rather pleased to have yet another show that sounded so slickly foreign yet still familiar, gobbled it all up like slices of processed cheese:

RICHARD: Well, Barbara, congratulations and felicitations!

BEN: Richard! Did that come out of you?

RICHARD: Sure - I know a lot of six cylinder words.

BARBARA: You mean syllables. A cylinder is something round and hollow. Like your head.

RICHARD: Thank you, dear sister!

BARBARA: Well, I can't help it. What's the matter with you, Richard - do you want to grow up illiterate?

RICHARD: I dunno - how are the hours?

Listened to, at its peak, by more than eleven million people each week, it would go on to spawn a version on the West End stage, two movies and a couple of separate series on commercial television. To those in the know, it served as a reassuring symbol of the continuing benefits of suffering from shortwave ear.

It would not be until the second half of the decade when the fashion would finally start to fade, and, when it did so, it was not primarily because of the warnings in The Green Book. It faded away mainly because of a couple of other developments that combined to dry up the well.

One factor concerned the belated modernisation of British comedy writing. The emergence, in the late 1940s and early 1950s, of a few new writing agencies (such as Ted Kavanagh's organisation and Associated London Scripts) would start to stabilise - and professionalise - the system by nurturing home-grown writers. Led by the likes of Denis Norden and Frank Muir (pictured), Spike Milligan and Eric Sykes, Johnny Speight and Ray Galton and Alan Simpson, this new wave of writers were far more interested than their predecessors in engaging with their own nation's culture and creating the kind of shows that seemed authentically and meaningfully British. They were stylists rather than recyclists.

The other development that started to atrophy all of the appropriations was the fact that American radio, in stark contrast to its British counterpart, was by this time in rapid decline. Network television was now the burgeoning commercial medium on the other side of the Atlantic, and the vast majority of writers and stars were thus being lured from sound to vision. Fred Allen, for example, bowed out of radio in 1950; Henry Morgan, along with George Burns and Gracie Allen, did the same in 1950; Lucille Ball left in 1951; Father Knows Best and The Adventures Of Ozzie And Harriet followed in 1954; and both The Jack Benny Program and The Bob Hope Show ended in 1955. More and more of America's top entertainers were moving their starring vehicles on to television, and radio, as a consequence, was left behind to wither away on the vine.

There was thus less and less left for British writers to listen to and lift. The copying culture was finally coming to a close.

What followed, as a result, was a whole new era of increasingly distinctive British radio comedy, with the character and quality of The Goon Show, The Al Read Show, Hancock's Half Hour, Beyond Our Ken, The Navy Lark, I'm Sorry, I'll Read That Again and Round The Horne. The kind of comedy shows, with the kind of figures, words and wit that could only have been created in Britain, by the British and for the British.

The BBC's much-mocked attitude in The Green Book to American material, therefore, should not be depicted these days as in any way 'reactionary' or 'insular'. It was, on the contrary, both a proper (albeit panicked) response to the widespread practice of plagiarism, and a positive step towards cultivating original and inventive home-grown radio comedy.

Looking back from now, therefore, we should celebrate the move rather than sneer about it. This was the start of the moment in the medium when we began to find things to laugh about from over the garden fence, instead of all the way from across the pond.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more