Setbacks & Fightbacks #1: The fall and rise of Max Wall

'Everyone has a plan,' Mike Tyson once said, 'until they get punched in the mouth.' It's a plausible enough sentiment no matter to what profession one belongs, and, as far as people in comedy are concerned, it certainly has its examples. The great comedians, however, managed to get back up off the canvas, beat the count, and get on with their careers.

One such figure was Max Wall. Long before the first Weeble wobbled, and Chumbawamba launched their chant, Max Wall found himself reeling from the punches, becoming, in the process, a kind of poster child for anyone else who was fighting against the fading of fame.

For Wall, the fall came in the mid-Fifties. One minute he was up, and the next one he was down.

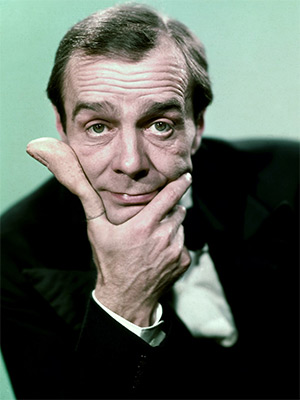

Born Maxwell George Lorimer in Brixton in 1908, he grew up in a family of music hall entertainers so steeped in the show business world that he made his own stage debut, regardless of whether he was aware of it or not, at the age of two. There was no doubt as to what future was being mapped out for him; the only doubt was how well, or poorly, he would fare once he was thrust into it.

He was trained as an eccentric dancer, dubbed 'The boy with the obedient feet,' and, from the mid-1920s, sent out on tour in a steady succession of music hall revues. Adapting his stage name from his stepfather, Harry Wallace, the young Max Wall soon became a master of his art (his remarkably fluid and flexible movements later inspiring countless imitations and tributes, right up to John Cleese's Ministry of Silly Walks), which he complemented with his own increasingly inventive comic patter (which he punctuated by punching the air every time he got a laugh and shouting: 'Success!').

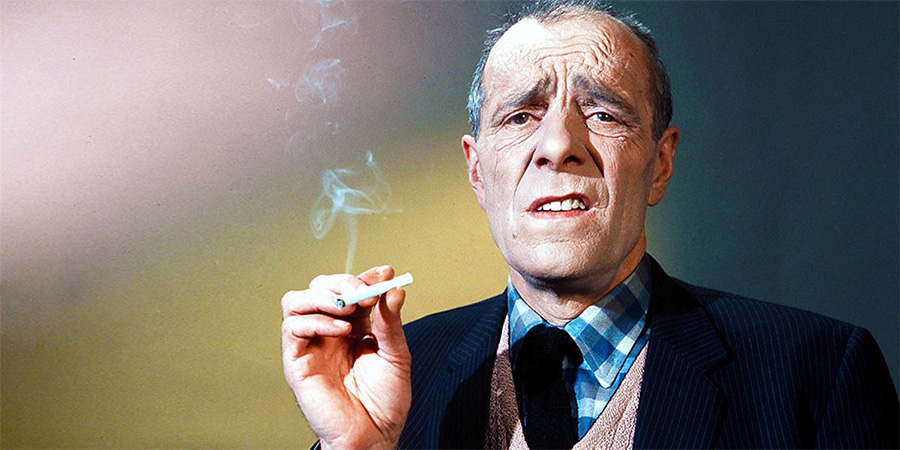

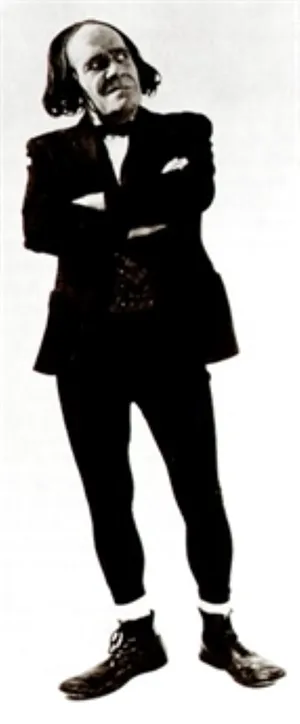

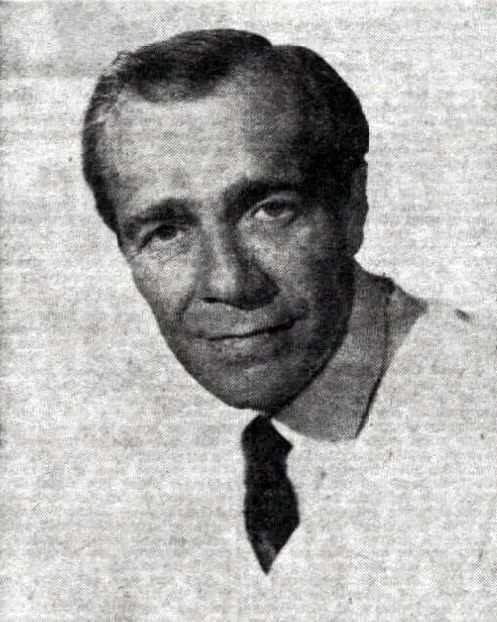

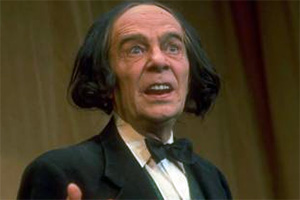

Deeply resentful about having been denied a decent education, and prone to depression, he could be a very difficult character to manage, but the natural lugubriousness (combined with the deep and droll nasal drone of his voice) was channelled quite cleverly to make his comic persona more interesting and edgy, and it was easy enough to admire his act, which was saturated in self-irony ('Max Wall standing before you, ladies and gentlemen,' he would start. 'In the flesh, not a cartoon. Man's answer to the peacock'). The highlight was his appearance as a character he called Professor Wallofski - a deeply eccentric figure sporting a long and dishevelled dark wig and dressed in a black dinner jacket, bow-tie, tights and big clumsy-looking boots, who would strut swiftly but strangely about the stage to the driving beat of a military drum.

Puckish and pawky, he was a powerful performer, strikingly different from anyone else on the variety circuit, and it soon made him into a star. By the late-Thirties onwards he was regularly placed high up the bill in the big London shows, earning increasingly large sums of money, building an even broader national following with his many radio appearances, playing golf with King Edward VIII and socialising with members of the aristocracy. Even Charlie Chaplin, one of Wall's own heroes, was moved, after seeing him perform, to call him 'the world's greatest comic'.

Then came the Fifties, and, still fiercely ambitious, Wall worked harder than ever to maintain his momentum, looking for new challenges and exploring different media (he even started adapting his act for the currently-fashionable arena of ice shows). He was a big star, but he was driven to be even bigger.

He was married (since 1942) to the former dancer Marion Pola, and had five children (twelve-year-old Michael, ten-year-old Melvin, six-year-old Martin, and the two baby twins, Meredith and Maxine). He lived with them all in a smart Edwardian house (dubbed 'The Seven Walls') in Park Avenue, East Sheen, Surrey, and everything about his lifestyle seemed to echo his famous catchphrase: 'Success!'

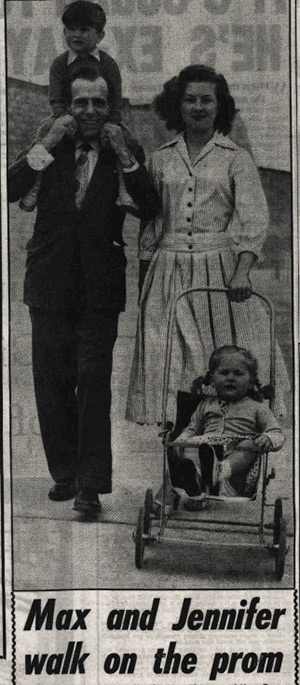

Always a mercurial sort of character, never inclined to camaraderie, Wall had probably made far more enemies than friends within his profession on his way up to the top, with some of his fellow comedians resenting his arrogance while envying his wealth ('He was a brilliant comic,' commented Charlie Chester, 'but he was not a loveable man. He could be very aggressive'). At this stage in his life, however, he appeared to have found some kind of contentment, both in his professional life (which had now just about reached its peak) and his personal one (he had recently posed for a series of publicity pictures featuring him playing with his young children, and looking adoringly at his wife, like a husband who could not be happier).

The year 1956 thus started off for the Wall family with yet another projection of this positive image of domestic bliss. On 3rd January, Marion wrote in a newspaper that, although she had once been a performer herself, she had no regrets about giving up that career because she now found the role of a 'full-time wife and mother [far] more rewarding'. 'In our household,' she went on to say, 'the seven of us share a million jokes, and I enjoy the sort of companionship which could never be found in a career.'

Max himself certainly had every reason to look forward to the new year. His role in the hit West End musical The Pajama Game (which had opened a few months before) had finally won him the kind of 'respectable' critical acclaim for which he had long been craving; his new fortnightly prime time TV series, The Max Wall Show, was due to start being screened by the BBC at the beginning of February; and he was also embarking on an ambitious new venture as a Svengali figure, signing up talented young people on personal contracts with the promise to personally plot their route forward in show business.

Then quite suddenly it all started to go horribly wrong. Before the month of January was over, Wall's marriage had collapsed. Then, at the start of February, his new series was undermined by a musicians' strike.

The news of the separation from his wife was, initially, treated sympathetically by the press, who expressed respect for the estranged couple's privacy, and hope that their problems could be overcome. The disruption to the show, however, seemed only to spark a certain amount of schadenfreude. One critic - noting that the programme had been billed as 'a half-hour of music and laughter' - sneered, 'The loss of the music could be explained. But what happened to the laughter?'

Things grew far worse for Wall that spring. On 11th April, it was announced that he was being sued for divorce by his wife after fourteen years of marriage. The decree nisi was granted in the middle of May, with Marion being awarded custody of the children.

Then came the scandal. Two days after the divorce was confirmed, it was revealed that Wall had been in a relationship for several months with one of his protégés (whom he had signed up on a five-year contract). Her name was Jennifer Chimes, the 1955 Miss Great Britain and a married mother of two small children, who was his junior by a quarter of a century and had only a few weeks before made her TV debut as a singer on his own show.

Speaking to reporters, the twenty-two-year-old Chimes announced excitedly that she and Wall were 'very much in love and very happy,' and they planned to marry 'as soon as my husband divorces me'. She also said that, although he had taken her on as a budding performer, she was now going to abandon her nascent show business career 'to be a wife to Max and a mother, running a happy family'.

It appears that Wall himself had not intended to be quite so candid about the relationship; the only comment he made, when questioned separately the same day, was merely to acknowledge that he and Chimes were 'good friends'. Once her quotes were published, however, he knew what kind of reaction was coming.

Like sharks spying blood, the tabloids (never needing much prompting to provoke the public into what the historian Thomas Macaulay called 'one of its periodical fits of morality') seized on the story and started tearing Max Wall to shreds. Poignant-looking pictures of the 'ash-blonde' Chimes with her young son (aged four) and even younger daughter (eighteen months) were plastered all over their pages, along with some plaintive quotes from her shunned insurance agent husband, Frank ('He was supposed to be giving her singing lessons,' he raged), and some condemnatory columns about all of the pain and suffering Wall was causing.

The television critics followed suit. His show, which had recovered somewhat from its union-hit start, was now subjected to a noticeably more negative set of reviews, as every flaw - which had previously been either largely ignored or explained away - was now magnified for forensic inspection.

'I have just one piece of advice,' one reviewer (who had only recently pronounced himself a fan) wrote by way of an open letter to the now-controversial comic. 'Finish your TV series, which gets drearier every fortnight, before it finishes you.'

The show did soon end - late in June - and many of the final reviews certainly did their best to finish him off, too, branding the series 'a depressing and dismal episode' which deserved to be instantly forgotten. The bad news, however, kept on coming.

Another wave of damagingly bad publicity arrived in July, when Wall was named as co-respondent in the divorce suit filed by Chimes's husband. The judge found in the husband's favour later that month, with costs awarded against Wall.

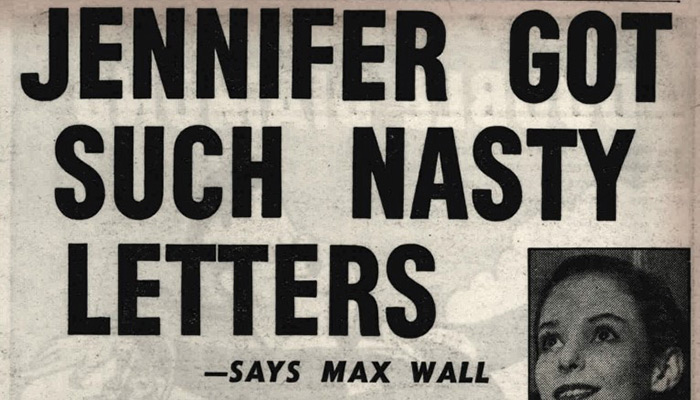

By August, he decided that it was finally time for him to start fighting back. Described as looking 'pale and tired', he gave several interviews to the press to complain about the 'hate campaign' that had, he revealed, driven his new partner into hospital. 'The upsets she has been through lately have worn her down,' he said. 'She has been getting some very nasty letters - which only goes to show how rotten some people can be.'

He also hinted that he might soon have to enter hospital himself. 'I have had as much as I can take.'

The strategy, on the whole, failed to work. The tabloids were as unsympathetic as before, and so, it seems, were those members of the public whose letters were picked for publication.

'So comedian Max Wall is complaining about people sending him nasty letters?' wrote one angry reader to the Daily Mirror. 'What did he expect - bouquets?'

Other negative stories started appearing, not only about the relationship but also about past 'unprofessional behaviour' by the comedian. Anyone, it appeared, with a long-standing grudge against him - and, in truth, there were quite a few - was now being given a public forum in which to vent their spleen.

The pressure continued to weigh down heavily on the couple, who in September announced that they were delaying their plans to get married 'until things have settled down'. They aimed, they said, to wait until Christmas, at the earliest, to decide on the date.

Whether that statement was made at the time with sincerity, or was simply intended to misinform the press, is contentious. What actually happened, however, was that they went ahead and married on 2nd November, at Brighton Registrar's Office.

It was a sign of how big a star Wall now was, and perhaps how controversial he had become, that hundreds of people, it was reported, gathered outside to see the couple emerge. Some, it was said, were there to cheer, some to jeer, and some simply to stare.

The new Mrs Wall (whose hair colour, it was noted pantingly, had been altered from ash blonde to auburn) was quoted as saying at the wedding reception that she and Max had had 'a terrible row' about ten days before ('We are both highly strung and life since our divorce[s] has not been easy'), but had reconciled a week later, and then decided to get married straight away. They both hoped, she added, that they could now be left to get on with their life as a couple.

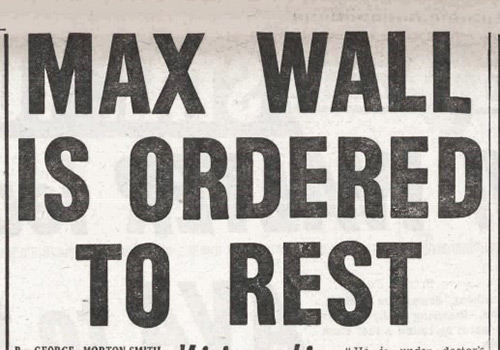

All of the trials of the past year, however, had taken their toll. Just a couple of months after the wedding, Max Wall suffered a mental breakdown. He left the cast of the still hugely successful Pajama Game, cancelled all of his other forthcoming engagements and entered a nursing home not far from his new flat in London's Bayswater Road. Jennifer, meanwhile, who was dealing with her own emotional issues, was left to struggle on alone and isolated as she tried to keep in some kind of control for the sake of her children.

Max returned to work after his rest, but was still resentful of what he sensed was a media-driven decline in his popularity. Often too absorbed by his own anger and anxieties to notice his wife's lingering distress, there would be some explosive rows at home, followed by some forced attempts to put on a show of public affection (both of them were painfully aware that the newspapers were actively and eagerly seeking any gossip that suggested their marriage was falling apart).

It looked as though a corner might have been turned when, in September 1957, ITV (albeit under the auspices, somewhat ominously, of the notoriously cheap and cheerless Jack Hylton production company) offered Max a return to television as the star of a new sketch series entitled That's Life. Delighted to be back, more or less, where he felt he belonged, but now, belatedly, more aware of how neglected Jennifer had been feeling, he resolved to get her involved in the project, persuading her to accept a small role in the opening episode. 'If it goes all right,' he said, 'she may do a little more in later programmes' (and, under the stage name of 'Jennifer Martyn', she would indeed make more appearances in the episodes that followed).

Any hopes or expectations that putting their relationship back into the public eye would help heal any wounds would soon be rudely disabused. The critics quickly complained about the nepotism, dug back up all of the so-called dirt, and dragged both of them through a fresh shower of hate.

The show in general was also damned definitively. 'It was without a smile for thirty minutes,' one reviewer moaned. Another condemned the 'chimp-like humourist' for using material 'which would not have satisfied Shrimpton Pier'. A third dismissed his efforts as 'lunacy without wit'. A fourth even decided to take great offence, on behalf of the entire country's working class, about a Johnny Speight-scripted sketch about one less than honourable plumber.

The knives were out, yet again, and the stabs kept spreading. There was arguably more than the odd reason for some people, quite legitimately, to dislike Max Wall, with some of their complaints concerning his behaviour towards past partners, and some to the way he behaved towards colleagues and the so-called supporting staff, but, by this time, the torrent of abuse was becoming relentless.

'The critics,' he lamented half way through the run, 'might have been more helpful in pointing out how [the show] could be improved, instead of coming down on the show like a ton of bricks.'

Increasingly rattled by all of the negative reviews, he took to arguing with the crew during rehearsals, cutting material at the last minute and relying instead on tried and tested routines from his past, or even losing faith in some sketches while he was actually performing them and trying to ad-lib his way to something better, which only caused further complaints about how jaded, and incoherent, it all seemed. No matter what he did, the ratings kept falling and the criticisms kept coming.

Once the series was over, he tried to sound bullish about the immediate future, claiming that he was in talks not only with ITV but also the BBC about his next television project, but, in truth, he was once again feeling worn out, and once again his marriage was in trouble. The couple would spend that Christmas apart, she in Warwickshire with her parents and two children and he, much to the tabloids' fascination, with his ex-wife Marion and their children in New Barnet.

1958 would be yet another year of more or less relentless misery. It started with Max, who was appearing in pantomime in Bournemouth, having to deal with the new speculation as to the state of his marriage.

There had been no row, he insisted, merely a pre-arranged break for the benefit of their respective families. '[The recently divorced] Roberto Rossellini and Ingrid Bergman spent Christmas together for the sake of their kids, didn't they?' he protested. 'Everyone understood why no one gossiped about a reunion between them. Why can't the rumour-mongers grant me the same kind of understanding?'

In reality, however, his life was continuing to spiral out of control. He was drinking increasingly heavily by now, which only made his eruptions of anger even more frequent and violent, and his behaviour was alienating more and more of those around him.

The newspapers, at this stage, seemed to finally be reaching the realisation that their chronic pillorying of Wall and his wife had probably gone on for long enough, and they started to settle instead on treating their ongoing troubles as more of an occasionally titillating soap opera. The damage, nonetheless, had been done.

Early in March, Max was arrested and fined for being drunk and disorderly after a policeman found him staggering along a pavement near his London home, shouting at no one in particular. A few days later, a forlorn Wall told one of the few friendly journalists he knew: 'I am very ill - physically and mentally'.

'For two years now,' he went on to say, 'I have been working under tremendous emotional strain. I have had mental breakdowns. Now I have cracked up again and it is not nice to know you have been arrested.'

'I am not thinking about work,' he concluded. 'I'm thinking about me. I am trying to sort things out with myself, that's all.' No mention, pointedly, was made of his wife.

A few days later, after he managed to get through a brief appearance on a BBC radio show, he finally admitted that Jennifer had left him. 'She said when she left it was for good,' he said. 'But I'm praying she'll come back like the last time she left me. It's terrible to be in love with someone who doesn't want you...'

The journalist with whom he spoke would observe the following day that, while Wall 'has always been a rather sad little man,' he had 'never known him in such low spirits as I found him last night'. Wall would later claim to have been on the brink of suicide.

The following month, the couple were, much to the surprise of many, reconciled once again. Declaring their latest problems to be over ('All forgotten,' said Jennifer with a smile. 'We're very much in love'), they announced plans to work together again, with Max arranging for her to join the cast of a new play (a farce called The Gypsy Warned Me) with which he was set to tour a few weeks later.

In July, however, Max, quite perversely given his and Jennifer's past press-related ordeals, provoked yet another explosion of tabloid indignation by announcing that, as their play had failed to earn a run in the West End, he and his wife were embarking on a hastily-arranged tour of Australia, and he had not only decided that she should leave her two young children behind but had also chosen to inform them of that fact via a letter. 'My relationship with the children has always been a bit strained,' he said icily by way of an explanation. 'We have left them with Jennifer's mother.'

He added that, if the tour went well, the two of them would probably stay away a little longer. 'It should make me a lot of money if I'm successful,' he claimed, 'and I don't see why I shouldn't be.'

Any sympathy that had begun to grow for Wall before this incident now abruptly drained away. As if his callous treatment of his step-children had not been damaging enough, the papers soon added to the ignominy by highlighting his similar alleged neglect of his own five children.

'I never hear a word now, nor do the children,' his ex-wife was quoted as saying. 'He never writes, sends presents or anything.' One newspaper, after claiming that Wall had recently missed the birthday of his baby twins, responded by announcing that it had sent round a car-load of cuddly toys 'so they wouldn't be too disappointed'.

Max and Jennifer, meanwhile, actually remained in Australia for six months, only arriving back in Britain at the start of 1959. Few people in show business, however, seemed particularly pleased to see them.

Without any new projects being offered by radio or TV producers, Max went back to touring the halls, but, after being encouraged during his stay in Australia to try a coarser kind of comedy, he was surprised to find that it was not well-received back in Britain.

There were reports of audience members booing or walking out because of the 'blue' nature of some of his material, and it was said that on one occasion at the Sunderland Empire his pianist quit on the spot after taking exception to his increasingly 'vulgar' jokes. The extent of the outrage was probably exaggerated, but it certainly contributed to a growing perception that Max Wall was out of ideas, out of fashion, out of friends and out of control.

That impression was further strengthened by the news, in December, that he had either quit or been sacked from a revue called Christmas Crackers at His Majesty's Theatre in Aberdeen after only one appearance. 'I don't think the idiom of my act was appreciated,' he said somewhat loftily when he arrived back in London. 'It is a quiet humour and the Scots didn't like it.'

According to one Scot who had been present, however, Wall's account of the cool reception was something of an understatement. 'In my long experience as a theatre critic,' he wrote, 'only on two occasions have I seen a performer get the slow handclap. Max Wall got his, not because the audience did not understand his material, but because they did not like it.'

It was a sad way for him to end a decade that at one point had promised so much pleasure but had ended up providing so much pain. He began the new one with an act that now seemed rooted in a fast-fading age of music hall, a persona that appeared uncomfortably cold and aloof, and a personal reputation that to some extent now seemed in shreds.

Unsure of what else to do, he continued touring the provincial clubs and halls, although the venues were getting smaller and less appealing, and the payments were shrinking and, in his eyes at least, increasingly demeaning. He was often accompanied by his wife, who was still using her stage name of Jennifer Martyn, although her contribution was modest and her own morale predictably low.

Some shows were cancelled due to poor sales, and some weekly engagements were terminated early by the management. Wall was drinking heavily again, and Jennifer was sinking deeper into depression. By the spring of 1960, the couple decided that, in the absence of much being offered to them professionally in Britain, they would try their luck in South Africa, playing mainly to ex-pats in the big hotels.

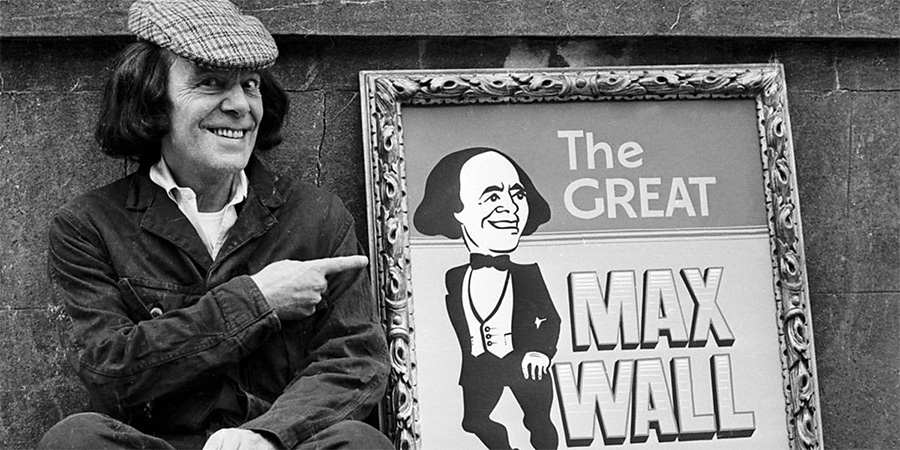

They were back home by the autumn, supposedly 'refreshed', and Max was claiming that he was all set to 'bounce back' in a West End musical-comedy called Once Upon A Mattress. 'Call me a big-head if you like,' he told reporters. 'But I'm a good performer. I know this is going to be a hit.'

It was not a hit. It was a miserable failure.

Wall's own contribution, to be fair, was regarded by some to be one of the few bright spots of the show, but the production as a whole was panned by most of the critics (it lacked, wrote one, 'any really distinguishing characteristics'), and it was reported that a significant number among the audience on the opening night greeted the curtain calls with a prolonged burst of booing. The show closed after a mere thirty-nine performances.

By 1961 Wall had been reduced to performing his old solo act in some of the Soho supper clubs run by the strip-show specialist Paul Raymond, and then, the following year, found himself toiling away on the hotel cabaret circuit. Sometimes he would go on stage drunk, sometimes he would end up abusing the audience, and sometimes he would walk off prematurely to a chorus of catcalls. Joylessness seeped out of him like a sour-smelling sweat.

Low-paid and under-appreciated, and seemingly abandoned by many of his old colleagues, he was deeply embittered about how far he had fallen. Convinced, more and more, that he had been effectively banned by most broadcasters, as well as some theatre managers, because of the fallout from the moralistic coverage of his marriage to Jennifer, he came to resent not only the media, but that relationship, too.

She, by this time, was feeling much the same. Still only in her late twenties, while he was now in his fifties, they had drifted apart in many ways, with different interests, tastes and outlooks, and the rows were happening more often and causing more lasting hurt.

Late in 1965, they decided, once again, to separate. 'Jennifer,' Max would say, 'is a restless girl.' He retreated to his holiday home overlooking the sea at St Helier on the island of Jersey, where he reflected on all the things that had gone wrong during the past decade, while she moved with her children to her native Leamington Spa, where she took on a part-time job working behind the bar of the White Lion pub in the nearby village of Radford Semele.

Regretting that she ever entered a beauty contest, she vowed now to 'slip into obscurity' and achieve 'a sort of peace'. 'I realise I did hurt a lot of people,' she would remark. 'But don't forget I've been hurt too.'

'I still see her occasionally,' Max said a couple of years later. 'The fact is I am still very much in love with her. I write to her, even send her poetry, but if she's happy then I'm happy.'

They would not divorce until 1969. After all the publicity they had endured during their time together, both of them made sure that their final parting happened so quietly that there was barely any mention of it in the press.

As for Max Wall's career, it did not die along with his marriage. It did, though, get even worse before it got any better.

At the end of the Sixties, while he was appearing in a summer season in Morecambe, he met another young woman, called Christine Clements, who was working nearby at, of all things, a dolphin aquatic show, and was thirty-three years his junior. They married in 1970, rowed almost non-stop, and divorced two years later. In the settlement, he lost his house in Jersey and most of his money ('I'll never forget my third marriage,' he later said. 'Don't think I haven't tried'). Soon after that, he was hit with a huge cumulative tax bill he no longer had the means to meet (due to the long press campaign against him, he claimed, his earnings were now a third of what they had been fifteen years before), and was subsequently declared bankrupt in November 1973.

He blamed many people for the impoverished state that he was now in: the press, the producers and his accountants all figured high on his long list. The nearest he came to including himself in this blame game was to express some regret about his weakness for women (his fellow comic Roy Hudd would later recall standing next to him in the gents in Grosvenor House, where Max stared down bleakly at his member and muttered: 'You! You little swine - you're the cause of it all!').

The man who had once owned three Rolls-Royces, two houses and an apartment now moved into a tiny £10-per-week bedsit in Hare and Billet Road, Blackheath, on the outskirts of south-east London, sharing the cramped bathroom and kitchen facilities with several of the other tenants. When Jennifer had left him for the final time, all those years ago, she had left a note behind that read: 'You will end up in one room, alone, with nothing'. Those words, right then and there, must have been echoing around his head, every day, and every night.

By this time, however, he was actually just starting to claw back some professional self-respect by testing himself in a succession of dramatic roles. It had actually begun back in the mid-Sixties, after a long and spirit-sapping spell touring northern clubland, where he sometimes left the stage to a shower of stale ale and empty beer cans, had left him desperate for, if not something better, then at least something different.

That was when he accepted a role as Père Ubu in Ian Cuthbertson's adaptation of the bawdy and boisterous French burlesque Ubu Roi (1966). Staged at Chelsea's Royal Court Theatre, the play allowed Wall a certain amount of freedom to improvise, and he used that to re-build his confidence as he stepped back out into the spotlight. Not all of the critics praised him (with some finding his skits too clumsily shoehorned into the script), but enough did to encourage him to keep exploring this area of entertainment.

More challengingly dramatic roles followed, most notably in Arnold Wesker's The Old Ones (1972), as Archie Rice in John Osborne's The Entertainer (1974) and, best of all, in Samuel Beckett's Krapp's Last Tape (1975). He was still often struggling for work - he even agreed to go on tour in 1972 with the rock band Mott The Hoople as part of their 'Rock and Roll Circus' (as an old dude to bemuse all the young ones - and he definitely did) - but, slowly but surely, he was starting to win back a few old friends, and attract some new admirers.

His revised and reinvigorated one-man show, Aspects Of Max Wall, which was launched late in 1974, became a striking tour de force, eventually breaking box office records during its long run, and had critics queuing up to praise it. Those who still remembered the classic days of variety, alongside those who were far too young to have experienced them first-hand, realised that they were seeing a very special kind of performance, a sighting of both a ghost of a bygone age, and a defiant survivor of its decline.

Wall published his autobiography, entitled The Fool On The Hill, in 1975, in which he worked hard to draw a line under his past problems and promote the notion of him now making a fresh start. It worked.

Suddenly he was back on the talk shows, the panel shows and the comedy shows, as well as the plays and the smarter sort of cabarets. Suddenly those who had been shunning him for so long were now looking to welcome him back into the fold.

It had taken Max Wall the best part of twenty years, but, at long last, his star was once more on the ascent. He had reclaimed the right to use his old catchphrase: 'Success!'

From that time on until his death, in 1990 at the age of eighty-two, he would remain busy again, well-paid again, and celebrated again. It was just a pity that, according to those who knew him, he never really seemed happy again.

The saga of Max Wall shows that there is a way back to the plan after the punch - sometimes. You'll need to have a very thick skin, and work really hard, and have quite a bit of luck, and a huge amount of patience and self-belief, as well as genuine talent, but not everyone who gets knocked down needs to stay down. Whether the fight back will end up feeling worth it, however, is quite another story.

Help British comedy by becoming a BCG Supporter. Donate and join us in preserving, amplifying and investing in comedy of all forms, from the grass roots up. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out moreMax Wall - The Fool On The Hill: An Autobiography

Comedian Max Wall's autobiography.

First published: Thursday 13th November 1975

- Publisher: Quartet Books

- Pages: 208

- Catalogue: 9780704320802

![]() Buy and sell old and new items

Buy and sell old and new items

Search for this product on eBay

BCG may earn commission on sales generated through the links above.