Kindly get on the stage: The real comic heritage of heckling

Hecklers, at their best, perform a necessary public service. They bring to mind Alvy Singer, in Annie Hall, stuck in a Los Angeles editing booth while a TV writer proudly demonstrates the corrective powers of a canned laughter machine: 'Give me a tremendous laugh here, Charlie... now give me like a medium-size chuckle here... and then a big hand'. A nauseous-looking Alvy removes his glasses, rubs his eyes and groans, 'Is there booing on there?'

That's why we need hecklers. None of the machines have booing on them.

What many hecklers, these days, fail to understand, however, is that the best hecklers are comedians. That's why they're up on the stage and we're down in the stalls.

The word 'heckle' actually has quite an honourable social heritage. It derives from the textile trade, where it was used to denote the practice of teasing or combing-out of flax or hemp fibres, and the modern meaning of the word emerged in the 1820s, when newly-unionised eastern Scottish hecklers, fighting back against their factory bosses and the prospect of being superseded by machines (one report of the time, about the hecklers of Dundee, noted that they had responded to the reduced terms being offered them 'with rather unbecoming indignation'), started interrupting morning meetings by calling out complaints and pointing out lies. It became a noisy form of truth-telling from those who are only in shouting distance from the official positions of power.

The very essence of a comedian is to heckle. That's basically what they do.

They heckle politicians, they heckle bureaucrats, they heckle bullies, they heckle jobsworths, they heckle snobs, they heckle hypocrites, they heckle authority. They heckle the worst parts of society as a whole.

There have, of course, been some memorable amateur heckles. There was the infamous time, for example, at the Glasgow Empire when Mike Winters, after straining the patience of the notoriously short-tempered and Anglo-phobic audience for a minute or so on his own, was joined on stage by his gurning brother Bernie: 'Aw, Christ,' groaned someone from high up in the gods, 'there's TWO of 'em!'

Then there was the occasion when a young Les Dawson, struggling in icy silence as a piano-playing comic in a tiny pie and gravy-fragranced northern club, finally thought he'd heard some solitary applause emanating from a sad-faced bald man seated in the shadows right at the back. 'Thank you for clapping me,' said Dawson, sensing that he had finally found a friend, only to be crushed by the man shouting back: 'I'm not clapping - I'm slapping me head to keep awake'.

Bernard Manning suffered something similar when he decided to take on someone who stood up and started leaving during his set. 'Where,' he asked aggressively, 'are you going?' 'I'm going for a pee,' the punter replied calmly, 'before the comedian comes on'.

There was also the moment when Cilla Black, unwisely back belatedly in her native Liverpool in 1986 to play Aladdin in pantomime, stepped forward towards the audience to ask them what she should do to punish Abanazar. 'Sing to him, Cilla!' shouted one sneering Scouser.

Then there was the truly bone-chilling incident when, at an open mic night, a novice stand-up comedian was struggling badly through his primitive routine when a sharp voice shot through the Stygian gloom: 'You're not funny and nobody likes you - you should have remembered that from school!'

These, however, are the exceptions - which is why they get quoted so often. Most heckles from the audience, on the contrary, are barely comprehensible, generally forgettable, and serve only to confirm why the drunken and slightly swaying skinny-suited Alan from accounting, or the short-sleeved and over-excited Lee from IT, do what they do instead of doing comedy as a profession (surely only a fool, for example, would pay fifty pounds or more to shout 'garlic bread' at Peter Kay when he can shout it back at you, as you're being frog-marched out of the auditorium, for free).

Maybe it owes something to The Muppet Show. Those two hoary in-house hecklers, Statler and Waldorf, were good enough to make plenty of viewers start fancying following suit:

WALDORF: They aren't half bad.

STATLER: Nope. They're ALL bad!

MILTON BERLE: Now, just a minute. I've been a successful comedian for half of my life.

WALDORF: How come we got this half?

STATLER: I liked that last number.

WALDORF: What did you like about it?

STATLER: It was the last number!

KERMIT: Tonight we thought we'd give Fozzie Bear a rest.

STATLER: You're not giving him a rest - you're giving us a rest.

STATLER: Does this show constitute as cruelty to animals?

WALDORF: Not unless they're watching it!

FOZZIE: Now, tonight, I'm gonna try and put something new in my act.

STATLER: Yeah, like comedy, maybe?

STATLER: This show is off to a fast start.

WALDORF: Good, maybe it'll end quicker!

What those viewers failed to grasp, however, was that Statler and Waldorf were scripted. Most real-life hecklers, in contrast, are merely Brahms and Liszted.

The typical club heckler is more reminiscent of George Costanza from Seinfeld, whose brain cranks its way towards what seems a suitably cutting line far too slowly to command the moment, thus causing him, out of sheer frustration, to search frantically for ways to recreate the situation so that his belated 'zinger' will not be wasted. These hecklers, in similar fashion, tend to spring up and emit a strange guttural yodel while they wait for something coherent to creep out of their mouths, and thus merely draw attention to their own chronic incompetence.

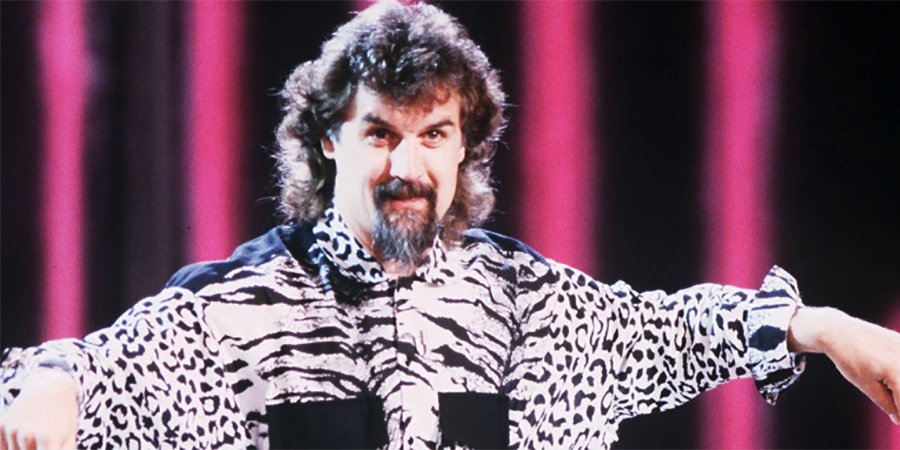

As Billy Connolly, that most outspoken of heckler-haters, once put it: 'If you want to speak, get up in front of the microphone and speak - don't sit in the dark hiding. It's easy to hide and shout and waste people's time'.

If you really want proper heckles, therefore, you should leave it to the experts. The experts are the comedians themselves.

They are the masters of the conventional, reactive and retributive, heckle. Eric Morecambe, for example, was like an assassin with a hidden switchblade when in the company of bores, able to slip the knife in between the ribs with the minimum of fuss.

On one occasion, for example, he found himself sitting at the same table as a particularly pompous promoter who was sounding off on the subject of 'making it' in the industry. 'To be in show business,' he droned, 'you must have three things...' Morecambe, sucking on his pipe, quickly interjected: 'If you've got three things, you should be in a circus'.

On another occasion, when seeing the tetchy-looking celebrity astronomer Patrick Moore enter the room, he shouted across at him: 'Hello, Patrick. Where did you get the suit?' 'Why?' Moore replied. 'That,' said Eric, 'was going to be my second question.'

A particularly memorable 'sort of' heckle was delivered, with its target in absentia, by the round, monocle-wearing and permanently lugubrious comic actor Fred Emney. He was appearing at the time in a production of the J. B. Priestley play When We Are Married when, one evening, the whisper whirled backstage that the playwright himself was in the audience. Once the performance was over, therefore, the company gathered together excitedly backstage in the expectation that the great man would come round and congratulate them.

When he failed to show, however, there were many crestfallen faces. 'Oh well,' sighed one as he broke the prolonged silence, 'I guess he didn't like it'. This caused Emney's monocle to pop out. 'Didn't like it?' gasped the actor. 'Didn't like it?? If he didn't LIKE it,' he barked, 'he shouldn't have bloody WRITTEN it!'

Sometimes, however, comedians can be far more proactive in their heckling. Tommy Cooper - proving that nobody is better at spoiling a joke than those who are best at selling them - was a specialist in this particular, and sometimes rather cruel, art.

Barry Cryer remembered a time when he and Cooper, while they were rehearsing in a church hall in Hammersmith, decided to pop out for a drink in the Britannia pub nearby. There was hardly anyone in there except for one man standing at the bar, who looked up and exclaimed excitedly, 'Oh, it's Tommy Cooper! Can I tell you a joke?'

Without waiting for a positive response, he launched straight into it: 'Two men walk into a pub...'

Cooper, blank-faced, suddenly interrupted and said, 'Hold it'. He then turned to the barman and asked, 'Have you got a bit of paper?' He took the piece of paper, smoothed it out on the counter, and looked back, still blank-faced, at the man, who continued: 'Two men walk into a pub...'

Cooper interrupted again: 'Have you got a pen?' he asked the barman. The barman handed him a pen. Cooper scribbled in the corner of the page to check that it worked, dictated slowly to himself as he scribbled, 'Two men...walk into...a pub...,' and then, still blank-faced, his pen poised over the paper, stared back at the man again, who was now starting to look nervous.

More hesitantly, he started yet again: 'Er, two men walk into a pub...'

'Is the name of the pub important?' Cooper asked, seemingly earnestly. 'Er, no,' the man replied.

The actual pub, by this stage, was beginning to fill up. Word had got out that Tommy Cooper was on the premises. A crowd was thus starting to gather around Cooper, Cryer, and their uninvited guest.

The man, now glancing around anxiously and blushing with embarrassment, was still doggedly trying to re-start his joke: 'T-Two men walk into a pub...'

This time he was interrupted when Cooper spotted a cameraman from the show popping in for a pint. 'Hey, Harry, come over here - you've got to hear this joke,' Cooper called out, then he turned back to the man and said, 'Would you mind starting again?'

That kind of brutal heckling (a kind of payback time from the comic to the punter) came all-too easily to someone like Cooper. As he hated having his pub visits, let alone his on-stage performances, disrupted by the babblings of amateur stand-ups, he resorted to such tricks - pour décourager les autres - on a regular basis.

On another such occasion, he was standing on one side of a horseshoe-shaped bar when, straight across, a man spotted him and started shouting out a joke. Cooper, gazing at him dead-eyed, furtively undid his belt and buttons and promptly dropped his trousers - causing everyone behind him on his side of the bar to fall about with laughter. The hapless joke teller, having not even finished setting up the actual punchline, was left utterly perplexed as to why so much hilarity had already broken out.

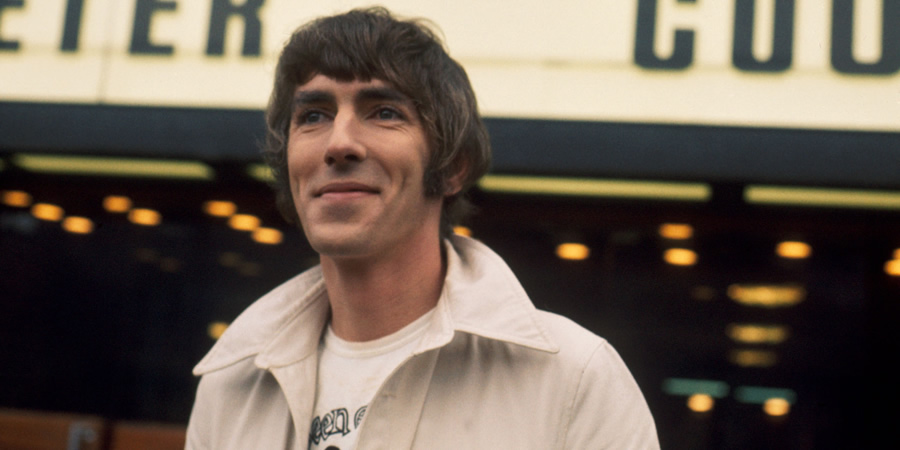

Considering the art of heckling as a whole, Peter Cook was probably as natural, instinctive and brilliant an exponent as Britain has ever produced. His double act with Dudley Moore was essentially that of him acting as a heckler to Moore's performer, regularly making his partner choke with his ad-libbed interjections ('Are you enjoying that sandwich?'), and he could be just as effective when responding to ordinary members of the public.

On one occasion, for example, he was being shown round the Playboy Club in Chicago when a group of businessmen arrived and tried to jump the queue for a lunch booking. Upon being told politely that they would have to wait until those ahead of them had been served, the leader of their party exploded: 'Do you know who I am?' Cook, overhearing this, promptly seized the PA microphone and announced: 'We have a problem here in the front lobby which perhaps someone can help us with. We have a gentleman here who doesn't seem to know who he is. If anyone recognises this man, will they please come down to reception and help us respond to his query?' (When the humiliated Chicagoan reacted by snapping petulantly back at the comedian, 'Fuck you!,' Cook stepped in for a second time and said, 'You'll have to wait in line for that, too, I'm afraid'.)

It was rather fitting, in this sense, that when Cook was hired in 1978 to be the host of a new wave music show called Revolver, his brief was to heckle the studio audience. 'Hooligans!' he'd snarl in mock-disgust, 'take a flame-thrower to them,' before causing widespread confusion with some or other jarring non sequitur (e.g. 'If three men with two buckets containing eight potatoes walked for three miles, discarding one potato every four inches, how long would it take them to get back?'). The posse of young punks, normally so eager to spit out their own abuse, were pictured standing about looking more than a little unnerved.

Cook's exceptionally quick and cutting wit rendered him more or less heckle-proof. For the rest of the comic fraternity, however, the possibility of some or other sozzled shouter spoiling the structure of a funny story continues to pose a threat.

In the context of their own working environment - although the odd comic can sometimes, to a certain extent quite understandably, snap after suffering one too many mouthy interventions (the rightly-shamed Michael Richards only being by far the most widely reported of the multiple on-mic melt-downs) - most comedians have a capacious enough cache of comebacks to silence any off-stage snipers:

Ah, yes - I remember my first pint.

Your bus leaves in ten minutes... Be under it.

This isn't TV, you know - I can hear you!

Well, it's a night out for him...and a night off for his family.

I'm sorry, I need a translator. I don't speak Stupid.

You look like you've been drinking since six. Or even younger.

If I'd wanted to hear from an arsehole I would have farted.

Isn't it amazing that such a big head can hold such a small mind?

Hey, I'm working here. I don't go to where you make your living and knock the toilet brush out of your hands!

Who else here thinks that birth control should be retrospective?

This is what happens when you drink on an empty head.

Sorry, I can't understand what you're saying - I'm wearing a moron filter.

Look: I like doing my act the way you like having sex - alone!

An alternative to such prêt-à-porter put-downs is to short-circuit the baiter's brain through sheer silliness. Harry Hill demonstrated this strategy memorably well when he reacted to one unwelcome interruption by saying: 'You heckle me now, but when I get home I've got a lovely chicken in the oven!'

Jeremy Hardy was similarly effective when he silenced a would-be persistent pest with the swift and sharp response: 'Nigel, it's over. Can't you understand that?'

Comedians heckling members of the public, however, is usually almost as otiose as members of the public heckling comedians. The professionals, rather than wasting their time on the wallies, are far better employed heckling those who claim some sort of superiority over the rest of us.

Some of them do this rather well, but they have the ability to do it so much better. Take, for example, Spitting Image.

This was a show that started out, with its Gillray-like bite, heckling politicians and other public figures with admirable power and persistence. Eventually, however, it lost its focus (there were plenty of professional and political reasons to mock the then-cabinet minister Roy Hattersley, for example, but instead the 'satire' centred on his speech impediment) and its ruthlessness (when many of your targets want to buy their own caricature, then clearly the blows are not causing a bruise, let alone drawing blood).

A similar thing happened with Harry Hill's initially brilliantly caustic TV Burp. It was remarkably subversive in its early days in the deceptively playful ways that it showed just how lazy, unoriginal and predictable much of the television output all around it actually was. Countless actors, writers and producers must have winced, and deservedly so, during each session with such a smiling assassin.

Eventually, however, it was emasculated by ITV, which started featuring various in-house soap stars, game show hosts and daytime presenters - some of the ostensible targets themselves - to 'request' their own 'favourite' (and predictably harmless) clips, and thus show what good sports they all were rather than admit what terrible television they produced. The boot up the backside had become a pat on the back.

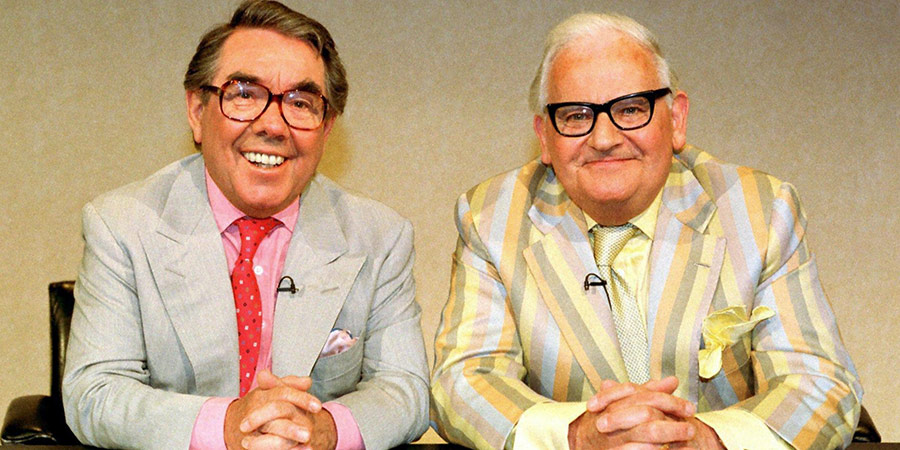

Contrast this with the occasion when the team behind Not The Nine O'Clock News decided to stick the boot into the team behind The Two Ronnies. There has never been a sharper, or crueller, example of one TV comedy show heckling another TV comedy show.

It happened in 1982, when the younger team featured a sketch called The Two Ninnies, which was a fairly brutal deconstruction of the still-popular but rather tired format featured in The Two Ronnies:

RONNIE B: And in a packed programme tonight you'll be reassured to know that we'll be using exactly the same sort of material...

RONNIE C: ...As we've used for the last twenty years.

RONNIE B: I shall be talking incredibly quickly, making spousands of Thoonerisms and dressing up in women's clothing.

RONNIE C: And I shan't be getting any laughs because he writes most of the scripts and makes sure I get all the crappy bits.

RONNIE B: Later in the show I shall be implying through smutty innuendo...

RONNIE C: ...That I have a very small part...

RONNIE B: ...And I have an enormous penis.

RONNIE C: And all the way through the show he will frequently cry...

RONNIE B: ...Spectacles!

RONNIE C: ...By which he means testicles...

RONNIE B: ...Cobblers!

RONNIE C: ...By which he means testicles...

RONNIE B: ...Didgeridooes...

RONNIE C: ...By which he means penises...

RONNIE B: ...Watermelons...

RONNIE C: ...Breasts...

RONNIE B: ...Articles...

RONNIE C: ...Testicles again...

RONNIE B: ...Bristols...

RONNIE C: ...Breasts again...

RONNIE B: ...And bouncers...

RONNIE C: ...Breasts OR testicles.

RONNIE B: This is because we are a family show and I will not allow smut into your home.

By mimicking most of their mannerisms and methods, and highlighting the increasing over-reliance on double entendre by replacing it with single entendre (e.g.: 'I spend all day just crawling through the grass/Thistles in me hair and bracken up me anus'), the newer show certainly made the older show suddenly seem, well, very old.

Both Barker and Corbett (two thoroughly decent and very talented, if by then somewhat tired, comic performers) were, understandably, deeply offended by what was basically an in-house heckle. 'Ron was very upset,' Corbett would later confirm. 'It seemed foolhardy of the BBC to let bright young things take the mickey out of the big Saturday night show. It seemed impertinent at the time and a bit daft to be hurt within your own territory'.

There had, however, been an essential truth in the critique, and, whether the 'real Ronnies' admitted it or not, it had been the truth that had really hurt. It did not leave them with any legitimate response other than to try to make their own show a little less comfortable and predictable.

That, for better or worse, was how to heckle another TV show. Having, say, Richard and Judy come on your show ('Hi Harry!') to cue an only slightly irreverent montage of Coronation Street clips was, as Mr Punch would say, not the way to do it.

A comic heckle needs to be as carefully considered as it is strikingly expressed. Spitting Image gradually stopped doing its research. TV Burp gradually stopped caring about its research.

More recently, the very talented Sacha Baron Cohen was guilty of a similar loss of nerve with his Borat Subsequent Moviefilm (2020). Here was an opportunity for him to effectively heckle a deeply elitist, depressingly complacent and profoundly morally-compromised national political establishment - and he chose to only heckle half of it.

Whether this was down to him believing that helping one bad bunch of scoundrels overcome an even worse bunch of scoundrels was a sign of sophisticated Realpolitik thinking worthy of Machiavelli's The Prince, or an even more deluded kind of Manichaean-driven mission to serve the sort of smugly complacent 'progressives' who would have made Thomas Paine throw up in disgust, remains unclear. What surely is clear, however, is that it was just the kind of lazy, needy, clap-trapping sort of heckle that those drunks in the audience like to slur out.

The proper hecklers, in the traditional sense, don't have the time or the inclination to play silly ingratiation games. They don't pick sides, they just pick the truth - no matter whom it upsets and offends.

Proper heckling is for the courageous, not the cowards. If they want to heckle religion, then heckle all religions, not just the ones least likely to lead to threats of violent reprisals. If they want to heckle political corruption, then heckle it right across the spectrum, not just the really untrendy bits that the rest of the bourgeois elites don't mind seeing gone.

If they want to heckle, then they need to make sure that the heckle hurts everyone who deserves to be hurt by it. That's what proper comic heckling does.

Hecklers are not supposed to be useful idiots. They are supposed to be the smartest critics: some of the best at flicking fleas in the ear, and among the most unbearable pains in the neck.

So let's have more of it on the stage rather than off it, and let's see it aimed at the right targets. The British-born John Oliver, in his much-celebrated US TV show Last Week Tonight, is showing the way at the moment, because his programme, with its precision of purpose and persistence of principle, is essentially a solitary but sustained heckle, the one rogue booing track amidst a cultural cacophony of canned laughter and unearned applause.

More of his fellow comedians, therefore, should now be following his lead. When the grand procession of would-be emperors parade past, soaking up all the cheers for the things that do not really exist, the comedians are the people who ought to be among the first to point the finger and shout out the shocking news: 'But they have nothing on!'

Help British comedy by becoming a BCG Supporter. Donate and join us in preserving, amplifying and investing in comedy of all forms, from the grass roots up. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more