Falling out of flavour: The curious career of Cheese & Onion

A quick bit of word association: what comes into your mind when someone says 'Cheese and Onion'? Possibly, first off, 'dairy and veg'? Secondly, perhaps, a particular flavour of crisps? Thirdly, just maybe, that song by The Rutles ('I have always thought/In the back of my mind/Cheese and onions')? It seems highly unlikely, however, that many of you will stick your hand up excitedly and shout: 'Cheese and Onion - comedy double act!'

There was, nonetheless, a comedy double act called 'Cheese and Onion' whose crash-and-burn flight into obscurity has, over the years, acquired near-mythic status. Their one claim to fame, if only they had been well-known enough for long enough to have had a claim to fame, was that they could, arguably, be said to have seen off the long and distinguished era of great British double acts.

Comedy double acts in Britain had been an essential element in the entertainment world since at least the start of the Twentieth Century. Murray & Mooney, Clapham & Dwyer, Wheeler & Wilson, The Western Brothers, Nervo & Knox, Flanagan & Allen, Revnell & West, Elsie and Doris Waters, Jewel & Warriss, the Patton Brothers, Morecambe & Wise, Mike and Bernie Winters, Cook & Moore, Hope & Keen, Little & Large and Cannon & Ball - the double acts kept on coming, up until the late 1970s. Once Morecambe & Wise were gone, however, the sheer extent of their success left all of their would-be successors looking dated and uninspired by comparison.

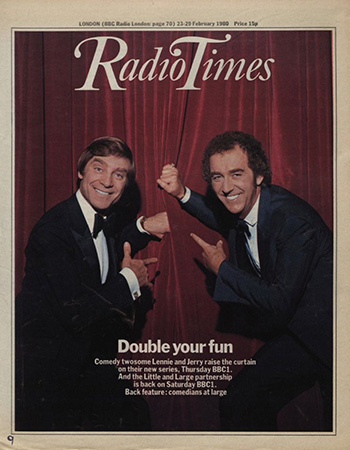

The BBC was so traumatised by the loss of Morecambe & Wise, and so driven by the belief that it simply had to have a double act in its schedules, that, in a moment of alchemic madness akin to Victor Frankenstein labouring away in his laboratory, it tried to create another double act under artificial conditions. It brought together two entirely unconnected solo comedians, Lennie Bennett and Jerry Stevens, and attempted by pure force of will to blend them together into a bona fide double act.

The BBC would pour a huge amount of time, money and expertise into making the experiment a success. Ernest Maxin, Morecambe & Wise's former producer, was given control over their joint career and an unusually large budget, and was provided with a rather desperate amount of hype to shape them into a pair of stars.

After trying them out as hosts of an ongoing variety show, they were given their own series, Lennie & Jerry (1978-80), occupying Morecambe & Wise's old Saturday night slot on BBC One, with a very similar format. The problem was, however, that although the two performers (who had the haunted look of two teenagers recently initiated into a dangerous religious cult) were very amiable and professional, they were simply not an authentic 'couple', and the audiences were quick to sense it, with The Stage referring to the series as the 'Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Show'.

That stung the BBC sufficiently for it to pull back and simply wait patiently for something organically comic and double to turn up on its doorstep. ITV, however, remained restless for a longer period of time. Still envious of the success that the BBC had enjoyed with Eric and Ernie, the commercial channel found it hard to stop hunting for a dominant double act all of its own.

This is where Cheese and Onion came in. It is also, alas, where Cheese and Onion went straight back out again.

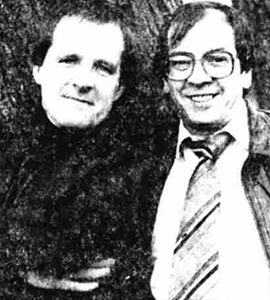

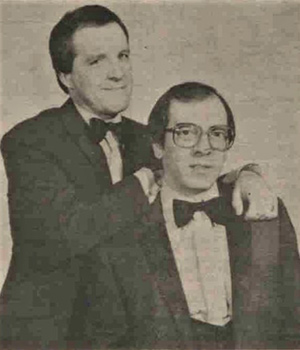

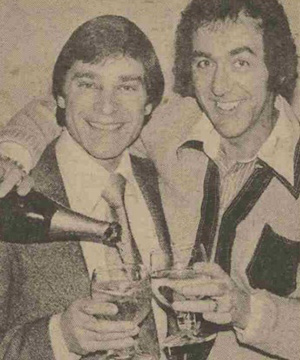

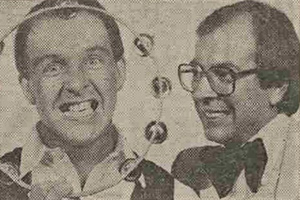

Cheese & Onion were, at the time, a young budding double act very much in the then-conventional style of Little & Large and Cannon & Ball. The act consisted of Barry Neal as 'Barry Cheese' and Michael Knight as 'Mike Onion'. Barry was the short (five feet three inches) and busy bundle of mischief with an addiction to 'humorous' props, while Mike was the taller, sterner, bespectacled figure with a weakness for big and bulbous bow-ties. They dreamed of becoming the new Eric and Ernie. They would fail even to become the new Mike and Bernie.

Both men were born in Rotherham in Yorkshire in the late 1940s, and had been friends since the early 1960s. Neal had worked for a while as a lorry driver, and Knight as a fireplace fitter, before both of them joined a local rock band (Neal as drummer, Knight as lead guitarist).

That association lasted for a couple of years, until Knight dropped out (deciding that it was time for him to find a 'proper' job) and Barry drummed on. They were reunited a couple of years later, when Knight, who was still struggling to shake the idea of show business out of his system, decided to form another band, and he recruited Barry as the man with the sticks. Once that adventure came to an end in the mid-1970s, they decided to form a double act - with Neal as the funny one and Knight as the straight one - and see if they could forge a joint career in comedy.

The story of how they came up with their stage name now seems somewhat symbolic of all of the peculiar wrong turns that followed. They had been rehearsing solidly for three or four months - during which time, apparently, neither 'Knight and Neal' nor 'Neal and Knight' had struck either of them as suitably mellifluous names for their act - when they got their very first engagement.

They were hired to do a 'turn', as Barry would later put it, at a local pensioners' party 'where they were having cheese and onion sandwiches, and the presenter didn't know how to announce us'.

A disinterested observer might have intervened at this point to suggest that 'Neal and Knight' had a certain ring to it, as did 'Knight and Neal'. It seems, however, that no such observer came forward. Instead, it was one of their wives.

'My wife Pauline', Barry would reveal, looked at the plate of sandwiches, looked at the two men (immediately discarding, presumably, the options of naming them 'Plate and Sandwiches' or 'Old and Hungry'), and 'came up with "Cheese and Onion" - and it stuck'. Barry Neal thus became known as Barry Cheese, and Mike Knight became Mike Onion.

They proceeded to play the circuit of northern pubs and clubs, from Leicester to Dundee, learning their craft at such modest venues as Gateshead Central Social Club (where they followed the faded pop group Paper Lace and were 'supported' by three 'exotic' dancers), and gradually piecing together enough routines in the hope of being ready for bigger and better things. The one innovation with which they came up was a fake brick wall that they used as a backdrop: it had mock graffiti all over it, which they would change on a regular basis, and it also served as a cheap and cheerful screen for quick changes ('It was mainly', Mike would later explain, 'to save Barry having to go off the stage for more props').

They kept working, kept adapting, and kept dreaming. The prospect of any big break, however, hardly seemed to be on the horizon. 'There were many times we sat waiting for the telephone to ring', Mike would later recall, 'hoping to get a night's work.'

It was at this point, in the autumn of 1981, that they were spotted by, of all people, Freddie Davies. As the bowler-hatted, lisping, budgie-obsessed Freddie 'Parrot Face' Davies, this show business veteran had enjoyed great success in the 1960s and 70s, on television as well as the stage, and had even had his own BBC children's series.

He was by now in something of a rut as far as his own performing career was concerned, and was trying his hand as a producer while he waited for the next viable personal project to come along. One day, as he went about his new business, a Yorkshire-based talent agency happened to invite him along to the Rotherham Trades Working Men's Club to run his eye over a selection of the local acts, and that was where he saw Cheese & Onion.

As Davies would later recall in his memoir, Funny Bones, he hated the name, but found some of their routines quite amusing, and felt they had potential. They were still very much a 'club act', he recognised, but, if they could be moved on to better venues, they might just grow into something that a broader audience would want to watch.

What happened next was both the best and worst thing that could have happened to Cheese & Onion. Alec Fyne, the head of light entertainment casting at ATV, happened to visit Davies in his office and noticed a newly-taken publicity picture he had of the double act. His curiosity duly piqued, he asked Davies about them and, knowing that ITV was searching impatiently for a new young double act to nurture, said he'd like to see them audition.

This was the best thing that could have happened because Fyne had the power to fast-track them into television. It was the worst thing that could have happened because they were nowhere near ready to be fast-tracked into television.

Davies, very wisely, urged Fyne to wait until they had acquired more experience and better material, but the booker would not take no for an answer, and Cheese & Onion soon found themselves in London, at Elstree Studios, to perform their act in the presence of several important TV producers. They did the best material that they had for ten minutes, the producers laughed a lot, and they were promptly signed up.

Davies was stunned - he had barely known them for a fortnight and now he was negotiating their arrival on the small screen. Cheese & Onion were even more stunned - they were set to go from northern working men's clubs to national TV in a matter of weeks.

An existing booking to appear in pantomime - Cinderella at the 624-seat Middleton Civic Hall in Manchester - was quickly cancelled by ATV on the double act's behalf, with the TV company compensating the local council by paying £500 for a new batch of posters and leaflets to be printed. Cheese and Onion were told that such humble engagements were now well and truly behind them.

Their introduction to Britain's viewers was via a guest spot on an ITV show called Starburst (which showcased a mixture of old and new comedy, music and variety acts) on 25th November 1981 (in an episode now sadly missing believed wiped). Even before this, however, ATV had already decided to give them their own series the following summer, and so, with the corporate hype dial suddenly cranked right up to eleven, they arrived on the screen having now been described as 'the comedy discoveries of the year' and 'the next great double act'.

Almost deafened by the cheering and applause, the two men faced the cameras and once again raced through their best material while trying their hardest to look as if they were used to dealing with this intensity of exposure. 'They brought the house down', Davies would later claim; 'there was a buzz around the studio, all about Cheese & Onion.'

One regular reviewer, the Daily Mirror's Hilary Kingsley, was enthusiastic about their debut. 'Mike Onion - the one with the glasses - almost brought tears to the eyes, he was that sharp and bossy, but Barry Cheese, a cross between Norman Wisdom and Bobby Ball, was rather appealing. I liked their timing, laughed at their jokes and look forward to the series they're soon to make.'

One regular reader of the Daily Mirror, however, was not so enthusiastic. 'L. Taylor from London' wrote in soon after to declare: 'I was astounded to see Hilary Kingsley praising comedy double act Cheese & Onion [...] I was even more astounded to learn that they are to have a series of their own. I thought their act was pathetic'.

Before the duo could actually make their show, however, ATV was restructured and renamed Central Independent Television, but their contract was honoured and the preparations went ahead. The two performers, still pinching themselves to test that it was not all a dream, wandered about in something of a daze, doing whatever they were told and assuming that the TV people knew best.

To outsiders, the first clue, after all the hype about this new signing, that ITV was not exactly one hundred per cent behind Cheese & Onion was the news that their first series, of which they were supposed to be the stars, was not going to be called The Cheese And Onion Show - as was the norm in the great tradition of comedy double acts - but rather Funnybone. As for the format, the advance information was vague to say the least.

On the inside, meanwhile, Freddie Davies, having found himself their agent almost by accident, was increasingly alarmed by what was happening behind the scenes. He heard from Central that the plan now was for Cheese & Onion to share the show with an eclectic assortment of other performers, including a Solihull-based Jasper Carrott-style comic 'raconteur' called Malcolm 'Malc' Stent; a comedy magic and mime act named Sonny Hayes & Co (the 'Co' was one woman - an ex-social worker named Sally Windross); and an actor and comic monologist called Nina Finburgh. As if this reduction in their role was not worrying enough on its own, Davies was also concerned about the thinness of the scripted material they were being handed.

He certainly had a point. All of the other acts were encouraged to use their own material, which would be added to and improved by the well-respected script editor John Junkin. Cheese & Onion, in contrast, had been assigned a part-timer by the name of John Palmer - a travelling salesman for a car seat cover firm in the Midlands.

The reasoning, such as there was any, appears to have revolved around the idea that what a novice double act needed was a novice writer with whom they could 'evolve a relationship'. It was a downright perverse idea that flew in the face of programme-making tradition, and seemed a reckless thing to do to such an unpolished pair as Cheese & Onion, but that was what the production team had decided, and that was what was happening.

Anxious to protect his new clients, Davies tried to coach them and suggest better lines and bits of business, but he was soon cautioned by the producer, the very experienced Colin Clews (who many years before had worked with Morecambe & Wise), and told in no uncertain terms either to shut up and step back or pull his double act from the project. Unable to face ending their improbable dream of stardom, Davies did what he was told and hoped for the best.

The best didn't happen. Funnybone made its debut at 6:40pm on Saturday evening, 26th June 1982, and it was a miserable mess. The low-concept rag-bag of a format was still so lazily loose that not even the description of any episode gave the curious viewer any real sense of what kind of show it was meant to be: 'Barry Cheese and Mike Onion invite you to join them in a unique version of a Punch and Judy show, while Malc Stent brings a touch of nostalgia as he recounts the amorous adventures of his youth at "the pictures". Nina Finburgh reveals some of the problems that beset a ballet fairy. The eccentric Sonny Hayes and Co try to rival Evel Knievel.'

What strange beast was this? Nationwide on acid? That's Life without the consumer bits? A sly Derridean critique of industry and audience conventions regarding form, content, coherence and purpose?

Whatever it thought it was, it was certainly not the right programme to showcase a budding double act. The critics, rightly sensing that this was one of those 'Will this do?' series ITV stuck on during the summer months when it assumed that many viewers would be away on their holidays, pretty much ignored the show right from the start (apart from the Daily Mirror, which branded it 'banal and unfunny'), and a large number of those viewers who were still at home soon followed suit.

As for Cheese & Onion, they staggered through it, doing what little they were allowed to actually do (they did still have their own wall, but were never really given their own heads), and grew more and more disheartened as each episode was greeted with nationwide indifference. Once it was over, it was painfully obvious that, in the space of five short weeks, they had gone, in the eyes of the media at least, from bright hopes to dull flops.

The producers of a summer season at the Wellington Pier in Great Yarmouth, who had signed them up so excitedly before the series had started, now greeted them with a look of disappointment. The publicity was practically non-existent, and the size of the audiences continued to shrivel as the weeks went on and the temperatures dropped.

The final two nails in the pair of coffins came soon after this, when Alec Fyne called Freddie Davies to inform him that Central would not be taking up the option of a second series of Funnybone, and also would not be working with his clients again. The second point was particularly brutal news, seeing that as recently as in late July of that year, Jon Scoffield - Central's Controller of Music and Entertainment - had let it be known to the trade papers that the channel was planning a proper starring vehicle for its new double act, with a view to broadcasting the six-episode series in November or December, 'to see where we can bring them to as performers'.

It seems that, at some point between July and September, Central suddenly had a rethink and came to the new conclusion that it had already 'brought' the performers as far as it could after all, and that was that. Cheese & Onion, less than a year after breaking into the big time, were back out of it again.

That was not quite the end for them. Freddie Davies had already arranged for the duo to appear in a pantomime (as the Chinese policemen in Aladdin) at the end of the year, and they would appear in another production of the same panto (but now placed lower down the bill) at the end of 1983. They then made what would be their final appearance on television on 8th August 1984 in the ITV variety show Entertainment Express, sharing the screen with Bernie Winters, Ted Rogers and Melvyn Hayes.

This now was indeed the end of Cheese and Onion. They announced their break-up shortly before the recording of the show went out. It was, they insisted, 'an amicable split': 'We simply decided we were going nowhere as a double act', said Barry, 'although we had been together for nearly ten years.'

Mike Knight, apparently, now wanted to leave show business and once again go off in search of that elusive 'proper job'. The Onion was no longer Mike.

Barry Cheese, on the other hand, wanted to continue being Barry Cheese and pursue a solo career. He had always been the dominant one of the two, the more outgoing and confident performer and media operator, and had already started working alone in summer season even before the break-up was made official. 'I have restyled my act', he said, 'and I wouldn't want to return to having a partner.'

Describing himself as 'one of the few comedians that can work right across the spectrum, clean or very cheeky - for young and old', his post-Cheese and Onion career (in spite of Bobby Ball claiming that he was 'one of the funniest comics in the business') failed to get very far off the ground, and it was not long before, as far as a national audience was concerned, he slipped down the back of the show business sofa.

He worked at entertaining on cruise ships, hosting corporate gigs and compèring rowdy sports nights, as well as touring the clubs (where The Stage newspaper still rated him, in the late 1990s, as 'one of the best stand-ups on the circuit'), until his retirement a decade or so ago. His endearingly eccentric-looking personal web site, Barry Cheese ('BARRY IS NOW RETIERD' [sic]), continues to entertain in his absence.

As for the artist formerly known as Onion, little is known of what happened to Mike Knight. For some years after the break-up, Barry Cheese was often heckled with the slurred inquiry, 'Where's Onion?' - to which his stock response was, 'He ran off with a dancing girl'. Where he really did go is, as he wanted it to be, perhaps best kept private.

TV, meanwhile, continued to dabble, for a short period, in mainstream comedy double acts - Hale & Pace, for example, were indulged for quite a time - but the faith was fast-waning. Whenever anyone suggested plucking a pair from relative obscurity and gambling on them coming good, it took just three words - 'Cheese and Onion' - to shut that discussion down.

The tragi-comic fate of Cheese & Onion, however, was simply so odd that it has kept their names fluttering in and out of Britain's comic consciousness ever since their demise and the decline of double acts in general. In a 2018 episode of Inside No. 9, entitled Bernie Clifton's Dressing Room, Reece Shearsmith and Steve Pemberton appeared as 'Cheese and Crackers' - a pair of washed-up entertainers who bore something of a family resemblance to Barry and Mike, while in the same year Danny Robins's darkly comic play End Of The Pier featured Les Dennis as one half of the long-since disbanded double act 'Bobby Chalk and Eddie Cheese', who were similarly reminiscent of the era, if not so much of the duo.

It seems likely that the memory of the real Cheese and Onion will live on, in its own strange little way, as an emblem of dashed dreams, over-hyped hopes and chewed-up and spat-out double acts. It is easy to chuckle at the naffness of their name and the daftness of their designs, but it also isn't too hard to feel rather sorry for this pair of good-natured optimists for whom TV arguably, once again, failed in its duty of care.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more