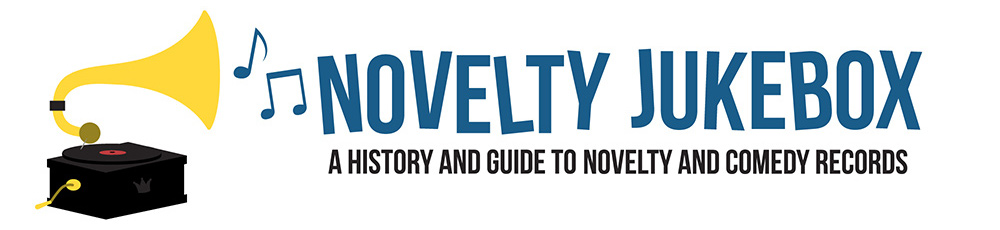

Max Miller - Max At The Met (1958)

1958 - Max Miller

Max At The Met

Pye Nixa NPT19026

There'll never be another!

Some sixty years on from his death, the name Max Miller is still a byword for comedy genius. Often cited as one of the greatest stand-up comedians of all time, Miller was a true master of his craft. With a reputation built on his repertoire of risqué material and adult jokes, he was a master of comic stagecraft who exerted absolute dominion over an audience. Nobody who was lucky enough to have seen Max Miller in his prime was ever passive or disinterested; they were drawn in, confided in, cajoled and manipulated by a consummate skilled comedian.

Miller was born Thomas Henry 'Harry' Sargent, in the English seaside resort of Brighton, in 1894. The fifth child in a family of twelve, Max Miller's early life reads like some grim, yet darkly comic, Chaplinesque evocation of poverty. It was by all accounts a precarious existence, full of moonlight flits to escape rent payments, with Max and his siblings clad in tattered hand-me-down clothing, walking the streets either barefoot or with oversized boots held together by string. What always raised Max above the bleak poverty surrounding him was his confident self-assurance and brash swagger, neither of which he had any real right to possess.

Leaving school at the age of just twelve, barely literate but full of that confidence and assurance, Max breezed through a variety of jobs to earn money for his family. Work in chip shops and dairies, bird catching expeditions to the South Downs, and stints caddying on the local golf courses all kept the money coming in. The young Max also became a regular in the pubs around Brighton, where he would sing songs with his father accompanying on the piano, in exchange for loose change from grateful drunken punters. Later in life as he grew rich and successful, Max's frugality and stinginess with money became legendary. It was a parsimony born in those difficult, perilous times.

Another outlet for the young Max was the Territorial Force, the part-time volunteer reserve of the regular British Army. For years he had enjoyed the irresistible chance to escape the slums of Brighton on manoeuvres, to breathe fresh air and to be fed regular, solid meals. When the First World War broke out in 1914 Max and his fellow Brighton Territorials volunteered for overseas service, and he was dispatched to the British army town of Mhow, in Madhya Pradesh, India.

There, Max, serving as the comically named Private Sargent, delighted in taking part in army concert parties, dutifully collecting hair from the regiment's horses in order to fashion wigs so that he could play female roles convincingly. In between that (and seducing the occasional officer's wife) there was little actual action until a posting to Mesopotamia in 1915. The horrors of that campaign to relieve the siege of Kut Al Amara, in a harsh desert environment full of antagonistic insect life and extremes of heat, would live long in Max's memory. His ordeal was compounded when a stray artillery blast blinded him for a full three days. For all Max's miserly attitude to money, he would always donate money to blindness charities, even gifting his home to the state, to be used as a convalescent home during the Second World War.

After demobilisation Max was set on pursuing a career in showbusiness and did so with dedication and conviction. Gone were his itinerant chancing ways. The war had matured him and given him a definite goal. Like his contemporary Arthur Askey, Max Miller took to performing in beach concert parties. But where Askey had a settled family life and a comfortable office job to fall back on, the fear of poverty and destitution loomed large for Max and provided him with the motivation to succeed.

It was in 1921 during his time with Jack Sheppard's concert parties on the beaches of Brighton that Max met his future wife Kathleen Marsh. The two formed a double act which met with some minor acclaim, but it was Kathleen's business acumen and savvy that proved pivotal to Max's career. The daughter of a blacksmith, and sister to the future mayor of Brighton Ernest Marsh, Kathleen was refined, respectable and educated - qualities that definitely did not apply to Max.

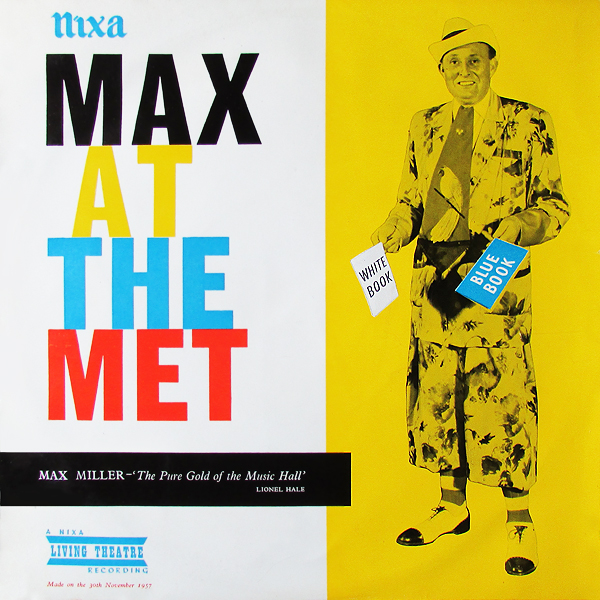

The double act soon dissolved but Kathleen was astute enough to realise that her partner had the ability to succeed as a solo act. She set about changing her husband's name from Thomas Henry 'Harry' Sargent to the much more appealingly alliterative Max Miller, and worked hard to correct his grammar and iron out the rougher edges of his working class Brighton accent. She also ensured that the phrase 'Cheeky Chappie', taken from an early review of his act, became synonymous with Max throughout his career. After their marriage, Kathleen would manage all of Max's business and professional affairs for the rest of his career. It was the perfect match.

For a performer of such renown and reputation, sadly there are not many examples of Max's work that exist for the modern comedy fan to enjoy. Unlike, say, the aforementioned Arthur Askey, Max's constant battles with the BBC over the suggestiveness of his material meant that he did not enjoy the usual long runs on radio or television that a comedian of his stature and popularity would normally have expected. The dozen or so feature films that Max Miller managed to complete did not play to his strengths either. Always confounded and stilted when asked to deliver another writer's lines, or to play a character other than his own inimitable Cheeky Chappie creation, Max was never truly comfortable on the big screen. His cinematic legacy has also suffered from quite scandalous neglect over the years. A total of five films, including his best work playing the titular horse racing tipster in Educated Evans and Thank Evans, are now lost. One of the few glimpses of Max in full flow on stage comes from footage featured in his 1940 film Hoots Mon!, which saw Max pay Harry Hawkins, an English comic attempting to make it in the music halls of Scotland. A daunting prospect for any entertainer!

Thankfully Max Miller managed to release a number of records over the course of his career, which capture at least some of the greatness of the man and his act. Those discs remain perhaps the best way to experience Miller in all his glory, although even that statement comes with a few caveats. There is for instance the nature of Max's material. His popularity in the halls had been built on his reputation for lewdness and vulgarity, with choice jokes carefully plucked from his fabled 'blue book' rather than the innocuous white one. When Max Miller's first vinyl album Max At The Met was released on Pye's Nixa label in 1958, the morality of the day would never have permitted a full and unexpurgated version of Max's risqué act to go on sale to the general public. And yet there on the front was Max blatantly brandishing the blue book, enticing record buyers by promising the prospect of a few choice saucy jokes.

The lack of visuals is also something an issue. Much of the power in Max Miller's act lay in his outrageous colourful suits, his accomplished stage technique, and his subtle winks and nods to an audience. Max did not simply deliver jokes. He spoke softly where others may have shouted, he developed an intimacy with the audience and took them into his confidence, leaning over the front of the stage to confess his mischievous misdemeanours to them, always furtively scanning the wings of the stage for imaginary censors and prudish managers ready to stop him in the act. Watching Max was not a passive experience, you were one of his confidantes, a mate being let in on a dirty joke, being talked to directly with eagerness and candour.

That first vinyl album, Max At The Met, was recorded at the Metropolitan on London's Edgware Road, in November 1957 and released the following year. It was one of the last hurrahs for a once-great home of variety, which had closed by the time the record was issued, and demolished just a few years later in 1963. The record does not capture Max in his early music hall days and much of his youthful energy and vigour had gone by this stage but his powers, honed over years of performing, were still incredible, and his audience were appreciative and thoroughly in awe of the legendary comic. There is - as you would expect for a record from the 1950s - no swearing and precious little filth beyond the usual cheeky innuendo and inference. Starting with, "a little song entitled 'last night I was in the mood, tonight I must get some sleep'", Max wastes no time launching straight into his act. The audience is there, expectant and ready to laugh along with a comic who had entertained them since the 1930s.

As soon as he takes the stage Max Miller owns every inch of it and is quick to work his audience, cajoling and admonishing them in equal measures, teasing them with the promise of some snippets of salacious gossip delivered in a furtive aside. Even without any visual images, the record is vital and alive, easily conveying what Max Miller was like in his prime. There is movement in every phrase and craftily delivered joke, a feeling just from the sounds that Max is breezing around the theatre, pointing to audience members, nodding at them, winking and flashing them his large blue eyes, his innocent cherubic face always aware of an unseen censor removing him at any moment. "You wicked lot!", as he often reminds them.

The topic are perhaps what dates the material more than, say, the delivery, which is still a consummate lesson in stagecraft. Not one to change his material regularly, Max relies on tested formulas and well-worn jokes for this performance. Even by 1957 his world is a vanished one, an evocation of the Edwardian Brighton in which he grew up. It is a seedy milieu of cheap seaside boarding houses, lascivious landladies seducing their lodgers, and unmarried couples sneaking away for a dirty weekend. Side one of the album sees old men with cramp seducing young ladies in a park, wicked squires taking away a young girl's honest name, a passing nudist, lion tamers, and soldiers enjoying the pleasure of ladies. On side two, there are saucy fan dancers, unmarried mothers, and the slightest hint of political satire with Max's take on Russia's five year plan. Dated though that reference was, it is still delivered fresh and as full of implied double entendre as it was in the 1920s.

Max Miller would often state that there would 'never be another' after he had retired, and he certainly had a point. Max's influence is clearly detectable in the blue jokes of Bernard Manning and the outrageous stage clothes of Roy Chubby Brown, and many eager working class comedians have a patter to match that of Miller, but no, there will never be another. No one comedian will possess all of Max's many virtuoso talents in a single package; his invention, his craftsmanship, his dexterity, his delivery and his sheer brazen cheek. Roy Chubby Brown cannot be charming, in a world where swearing and smut has replaced innuendo and inference. The world of Max Miller has gone, but thankfully his comedy and his legend will endure.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

Love comedy? Find out more