Re-writing Reluctant Persuaders without a studio audience

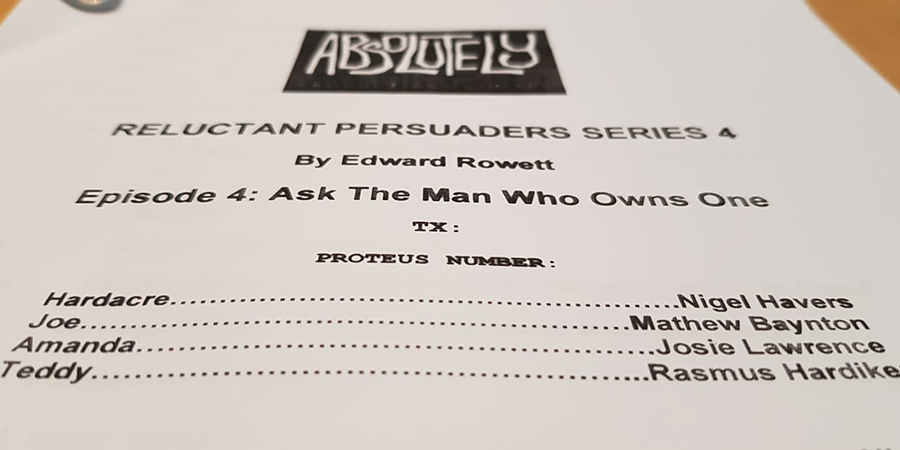

Edward Rowett created Reluctant Persuaders in 2015, a laugh-packed Radio 4 sitcom set in an advertising agency. However, as he explains in the article below, Series 4 sounds very different from the three that proceeded it, and required a different writing style too.

Reluctant Persuaders returns to Radio 4 this week for its fourth series, and for the first time without a studio audience. Because, for the better part of a year, audiences have been illegal.

When the pandemic hit, we were gearing up to record the series. I was writing the scripts, the theatre was booked for dates in May, and the show was set to go out in summer 2020. I remember the first pandemic-inflected conversation with producer Gordon in mid-March, where we confidently reassured each other that any kind of 'lock-up' was highly unlikely, and even if it did come to pass, we were bound to be out of it by May - in time for everyone to cheerfully gather at our recordings for a celebration of freedom!!

I also remember the conversations that followed. The horrible dawning realisation that we were in this for the long haul, and the prospects of gathering an audience any time in the foreseeable were... bleak. Somehow, the show must go on. But how, exactly? At this stage, even gathering the cast was illegal. There was talk of remote recording, actors huddled around laptop microphones across the country, and even a select audience gathered on Zoom. None of this seemed particularly inspiring.

One thing we knew for certain was that we didn't want to record scripts intended to play in front of an audience, without one. To a certain extent, funny is funny, and a joke is a joke. But to another more accurate extent, audience and non-audience are different formats that service very different types of comedy.

Studio audience sitcoms tend to thrive on clear characters, and big, clean jokes. A set up and a punchline, build and release. Done well, there's nothing funnier, and the sound of an audience responding adds to the joyful effect. What can be harder is to build jokes on top of one another - a good joke needs space to land with an audience. If you immediately try to cap it, you tend to end up with two jokes that get in each other's way. In the best non-audience sitcoms, jokes can be built, topped, subverted all in a few seconds, revealing themselves fully on repeat viewings.

When Radio 4 offered to push back the show's airdate to give us time to work out what to do, and hopefully at least gather the cast in one room, a plan began to form. Reluctant Persuaders would become a non-audience sitcom, and the scripts re-written accordingly.

It's not a transition many shows have made by choice, especially several series into their run. Once you've built a world that encompasses an audience, and characters who play off them, there can be something uncanny about hearing lines delivered into a silence that feels haunted by the ghosts of absent laughs. Jokes that were hilarious in front of an audience can suddenly seem laboured and lame. The established rhythms are thrown off.

As a novice writer when the show began, the challenge of the first three series has been learning to internalise the audience, to hear them while writing and sound the alarm when I've served them a page (or worse) of silence. The challenge of this series has been to turn that frequency off, and see where the scripts go without it.

The trap I predictably kept falling into was thinking the absence of an audience freed me from the distasteful necessity of writing jokes. There's nothing like a live audience for keeping you honest. The prospect of a couple of hundred people sitting in audible judgement on your script - and that judgement being recorded and broadcast as part of the finished show - inspires a kind of holy terror in a writer, forcing you to comb through looking for every corner into which a laugh can be squeezed. Without that phantom audience at your back, it's easy to feel liberated, to convince yourself you're writing a subtler, smarter kind of comedy... that turns out not to be funny at all.

Over the course of the writing process, I tried to find that balance between staying true to the characters and the world, while adapting to the new format. Like all writing, it's largely come down to trial and error. There are some jokes that made it from the initial studio audience drafts of the scripts into the final recording versions, so convinced was I they were strong enough to survive the transition. Most haven't made the final edit, falling victim to that strange airless quality, a punchline without any punch. Equally, certain recurring jokes built to play in front of an audience remain; dropping them four series in feeling like a betrayal of the characters and the audience's investment.

I don't really believe a studio audience limits the kind of story you can tell. The format gets such a bad rap, it's easy to convince yourself that it's a writing straitjacket. But the best examples of the form tackle themes of anxiety, depression, grief, existential angst - they just deliver them with laughs. All the same, I've tried to tell more interesting and complex stories this series, and exploit the practicalities of a lack of audience where possible - whether building a greater use of soundscapes and FX into the narrative, or following the comedy into stranger, darker places than I might previously have had the courage to go.

As a writer, it's all too easy to forget that the scripts are only one element of the show. The journey from page to radio is a long and collaborative one, which threw up just as many challenges.

The process of recording studio audience scripts is hectic. You do two in a day, progressing from read-through in the morning, to rehearsal in the afternoon, to recording in the evening. You have time to get the two episodes in basic working order, and then it's show time; the scripts live and die on the adrenaline and energy of the cast and audience, feeding off each other.

In a recording booth, that energy is gone, and can be hard to summon artificially. In front of 250 people, you know for sure if something is funny. In a small soundproof room, it can be a lot harder to tell. What you gain is the ability to work in more detail, trying things several different ways.

By and large, a scene tends to get worse the more it's performed in front of an audience. Even the most generous one in the world won't keep laughing at the same jokes. You only really get one shot at capturing a moment authentically. By contrast, every take in a recording booth usually improves on the one before, as the actors are free to try different things, and grow more comfortable with the words and each other. Reluctant Persuaders is blessed with a cast equally adept in either setting, and they've brilliantly taken advantage of the opportunity to find new and unexpected wrinkles in their characters.

My hope is that this series stands as its own distinct thing, rather than a pandemic-compromised version of what's gone before. And I hope if there were to be a fifth series, the choice of how to make it would be back in our own hands. But most of all, I hope it makes people laugh. We could all use one right now.

This article is provided for free as part of BCG Pro.

Subscribe now for exclusive features, insight, learning materials, opportunities and other tools for the British comedy industry.